Spin-off, sequel or sell out?

- Published

Former crime reporter David Lagercrantz is taking on the next chapter in Stieg Larsson's Millennium trilogy

Publishers, like film studios and broadcasters, have been trading off literary hits for decades. And 2013 was another bumper year of literary reinvention.

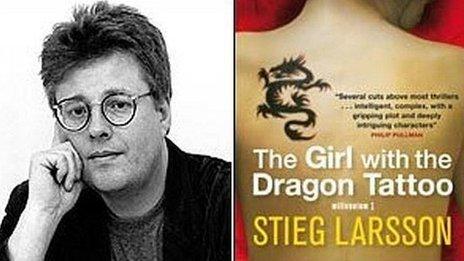

Earlier this month, a writer was hired to pen a fourth instalment to The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo - Stieg Larsson's hit trilogy that has taken the book - and film - worlds by storm.

Larsson died in 2004 while working on a fourth novel. David Lagercrantz has now been commissioned to take on the characters of Lisbeth Salander and Mikael Blomqvist, as Swedish publishers look to cash in on Larsson's cult creation.

They are not alone.

This year also saw Sebastian Faulks take on Jeeves and Wooster, William Boyd tackle James Bond and Joanna Trollope take on Jane Austen's Sense and Sensibility, as well as another spin-off of the ever popular classic Pride and Prejudice, in the form of Jo Baker's Longbourn.

There was also the announcement of a new novel featuring Agatha Christie's Belgian crimebuster Hercule Poirot, due for publication next year.

'Live on'

It's not a new trend by any means.

Some early 20th Century spin-offs, such as Jean Rhys's Jane Eyre prequel, The Wide Sargasso Sea, and Sir Tom Stoppard's Hamlet-led play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, have become classics in their own right.

Lagercrantz has argued the Salander character "deserves to live on", but Larsson's partner Eva Gabrielsson told Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet she thought it was "distasteful to try to make more money" from the books.

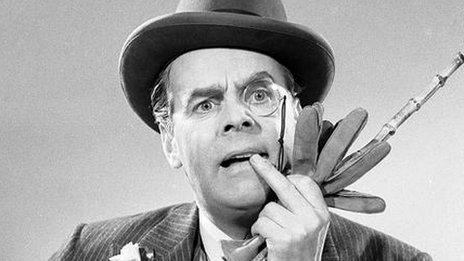

Wodehouse's family personally asked Sebastian Faulks to pen the new book Jeeves and the Wedding Bells, featuring the much-loved duo

"The Larsson question is a difficult one," says Jonathan Ruppin, web editor at Foyles bookshop.

"It was such an extraordinary phenomenon in publishing terms. Apart from JK Rowling, I have never come across anything that redefined a genre for readers in the way he did."

"Legal muddiness" surrounding the rights suggest people may be trying "to milk what suddenly became a very popular product," adds Ruppin - although he is keen to stress he is unaware of the particulars of the case.

British copyright law states the novelist, or their estate, has ownership of their work until 70 years after the author's death.

Fan literature

These days, continuation literature - as it has been hailed - falls into two camps: works that are licensed by writers' estates and those that, like Austen, are in the public domain.

"When there is an estate that understands the legacy of a writer, they do think very much more carefully about what projects they are prepared to endorse," says Ruppin.

"Think of something like Sebastian Faulks's new Jeeves and Wooster novel. He is a huge Wodehouse fan - and if anybody can replicate the way that Wodehouse writes, it's somebody like him.

"In the absence of PG Wodehouse himself, having somebody who is an established and clearly excellent writer - and a huge fan - is the best a fellow fan could hope for."

Spurred on by the proliferation of sequels in Hollywood - writers' estates have wised-up to the financial advantages of prequels, sequels and spin-offs but, where possible, remain in control.

William Boyd re-read all of Fleming's books in chronological order before writing Solo

The Ian Fleming estate has officially sanctioned a number of authors to write novels based on the James Bond character since Fleming's death in 1964.

Faulks, John Gardner and Jeffrey Deaver have all tackled the MI6 agent.

Boyd, who released Solo - the 38th book since Fleming's death - in September, is the third author to be invited to write an official novel by the estate.

Ruppin believes their success lies in their ability to ape Fleming's authorial voice.

"When I started as a bookseller in the '90s, there were various Bond spin-off novels that didn't get much attention - there were much more cash-in products.

"But William Boyd is an acknowledged expert on Ian Fleming and he is able to provide a book that adds to the character."

"People have learnt you can combine commercialising an author - and making a lot of money out of their estate - with a quality product. And ultimately you will retain readers that way."

Austen project

More than 200 years since she first put pen to paper, Jane Austen remains a phenomenal brand - with more than 70 re-workings of her six completed novels in print.

The author's works - which have long been out of copyright - are constantly being revisited, in books and on screen.

This summer saw Baker's Longbourn, a novel set "below stairs" in the Bennet household, meet with critical admiration on both sides of the Atlantic.

And in October, HarperCollins published Trollope's modern interpretation of Sense and Sensibility - the first in its six-book Austen Project.

Fans of Jane Austen - or Jane-ites - are often disappointed by modern versions of her tales

Alexander McCall Smith's version of Emma and Val McDermid's Northanger Abbey will follow next year.

All the authors must stick with each individual novel's existing plot and characters, but are free to make some changes.

Trollope herself advised Austen fans against reading it: "There are few fans of classic writers who identify themselves so intimately with the writer as Jane-ites," she told the Financial Times, external.

"They feel very close to Jane, and very possessive. And my message to them is, don't upset yourselves. Don't read it," she added.

"Speaking for myself, I feel I ought to read them but I cannot overcome my prejudices," says Maureen Stiller, honorary secretary of the Jane Austen Society in the UK.

"As a society, our objective is to bring people to Jane Austen, her life and novels," says Stiller, but whether the newer works actually lead readers or viewers to the original novels is "an open debate".

She maintains the reader or viewer who comes to Austen via sequels and adaptations may find modern expectations "may not be realised by the original novel".

'Dripping shirt'

Ruppin disagrees.

"I don't think there is a problem getting people to pick up Austen anymore," he says.

"The turning point was Colin Firth coming out of a lake in his dripping shirt and, at the same time, Penguin starting to issue their popular classic series - which you could buy for £1."

"All of a sudden the classics were transformed from being these stuffy books you were forced to read at school, into classic works of literature everybody realised had stood the test of time."

This Christmas sees PD James's 2012 thriller Death Comes to Pemberley - in which Lydia Bennet's husband Wickham is accused of murder - adapted for television.

Matthew Rhys, who plays Mr Darcy in the three-part drama, calls it a "very shrewd move" on the part of the respected writer.

"This doesn't set you up for direct comparisons of a sequel, and PD James is writing in a style that she's incredibly adept in, but still using incredibly famous characters," he told the BBC.

"It's a bit of a win-win… You're ticking a lot of boxes."

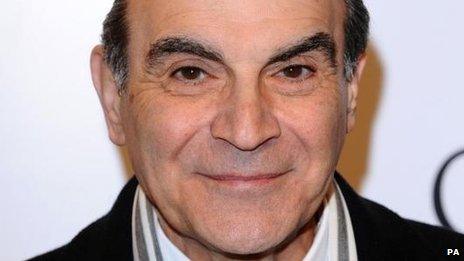

David Suchet bowed out as Hercule Poirot in Poirot's Final Case in November

Sophie Hannah's untitled Poirot novel comes more than 90 years after Christie introduced the Belgian detective in her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, published in 1920.

Her grandson, Matthew Pritchard, told the BBC the commission was motivated, in part, by waning interest in Christie's works - in particular among the younger generation.

"Sometimes series do come to a natural end," says Ruppin.

"Think about Eoin Colfer's writing of the sixth Hitchhiker book, which was born out of desire to do something for fans who felt they had been robbed early of a great talent.

"But Eoin Colfer just wasn't Douglas Adams.

"Some writers are unique. Nobody can write like Douglas Adams, apart from Douglas Adams - and we have lost him now, so unfortunately that means there won't be anything else that remotely comes up to scratch."

- Published19 December 2013

- Published17 December 2013

- Published4 October 2013

- Published21 October 2013

- Published25 September 2013

- Published4 September 2013

- Published8 February 2013

- Published7 March 2013

- Published16 March 2012

- Published13 September 2011

- Published3 August 2011