Why did theatre turn its back on original Peter Pan?

- Published

The Royal Shakespeare Company is about to open a new and reworked version of Peter Pan - now titled Wendy and Peter Pan. JM Barrie's story of the boy who wouldn't grow up is regarded as a stage classic, yet the original 1904 play has all but disappeared from view. Is there something about Barrie's writing that just doesn't work for modern audiences?

Sam Swann, the RSC's new Peter Pan, takes a breath and tries to explain what Ella Hickson's reworking of the play is and is not.

"Well, it still starts in Edwardian times, which of course is what the audience will expect. But the dialogue becomes more anachronistic when the story shifts to Neverland. There's plenty of flying and we still have Captain Hook and the pirates, but no dog."

Fiona Button plays Wendy. "We're looking at the story far more through Wendy's eyes this time. Her motivation for going to Neverland is new to this version and involves an important new character Ella has invented."

Barrie's Edwardian tale has attained a curious and slightly muddled status.

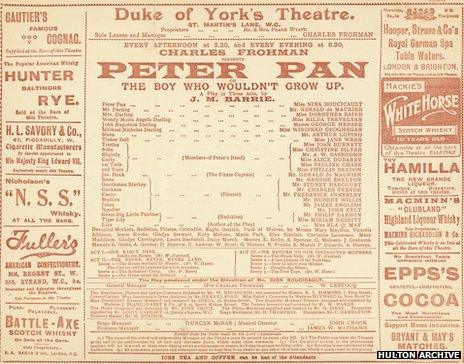

A version of the Peter character appeared in 1902 in Barrie's book The Little White Bird. Two years later the stage play opened in London at the Duke of York's Theatre and was a big hit. In 1911 Barrie wrote a novel based on his play.

On 27 December 1904, the first stage version of JM Barrie's Peter Pan opened at the Duke of York's Theatre in London

A year after its London debut, Peter Pan did well on Broadway and had several revivals. Yet in both Britain and America the story is now best known from the 1953 Disney cartoon and from assorted film and musical adaptations. Most are a long way from what Barrie wrote.

Swann's experience is probably now typical: his previous experience of Peter Pan was watching a pantomime version at the Birmingham Hippodrome. "But our flying is much better than theirs was - much more creative."

The Harvard academic Prof Maria Tatar is a specialist in folklore and mythology who recently worked on a new edition of Barrie's story.

"In America, Peter Pan is associated with a well-known bus company, and you often find him on peanut butter jars and bags of candy. But that just proves he's become a figure divorced from the original stories. Sherlock Holmes would be a similar case.

'Edgy character'

"In the USA it's hard to get away from the Disney view of Peter Pan. For instance, most versions of Peter now have him dressed in green, whereas he used mainly to be in auburns and tans and browns. But the Disney animators knew green was better for the camera and that stuck.

"But the character still works. He's edgy and uncanny and somehow connected with the world of the dead. So though Barrie's tone is often playful, you could also draw a parallel with the vampire myth we've seen so much of in popular culture of late.

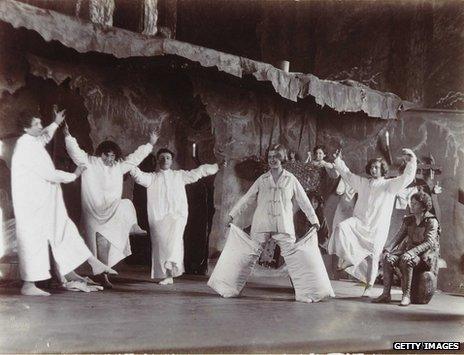

After the success of the original performance of Peter Pan in 1904, it toured every year for the next decade

"It goes back to the Brothers Grimm and beyond: stories which persist in the collective unconscious often have a darkness underneath."

Hickson says that when she went back to Barrie's originals - especially the 1911 novel - she realised how much the theme of death featured. "It's something Disney downplayed but I wanted to reverse that. Also the female characters get a rough ride in the original. I knew I needed to change that too.

"But my first draft was much closer to the original play and included almost everything. But I liberated myself from absolute purist loyalty quite early on. That wasn't wilful disobedience: tonally I felt I needed to shift the story quite a lot.

"A lot of what Barrie did on stage in 1904 isn't going to work now. Some of the characters are very saccharine, especially Wendy. A contemporary audience won't buy that.

"And, from a playwriting point of view, it's very expositional. So people are forever explaining at length how they feel and what they're about to do. That leads to lots of direct address, with the characters standing there talking to the audience. In terms of contemporary drama that's seen as non-dramatic."

Marital tension

Hickson hasn't hesitated to turn the narrative to her own interests. Some audience members may be surprised to discover real marital tension between Mr and Mrs Darling.

Jonathan Munby, the play's director, says the new version has a different view of the Darling household. "Something happens to this family - something not in Barrie's play or book - and Wendy has to deal with that. In fact you may decide that Wendy conjures Neverland as a consequence.

"We've tried to take away the baggage of all the films and cartoon versions. So yes, we're fresh-minting it and adding new ideas of our own. But crucially, we're also looking again at Barrie's original story and staying true to his ideas. The story ultimately is about a family finding happiness again."

Tatar says Peter Pan will always remain irresistible for those who want to build on it to explore new ideas.

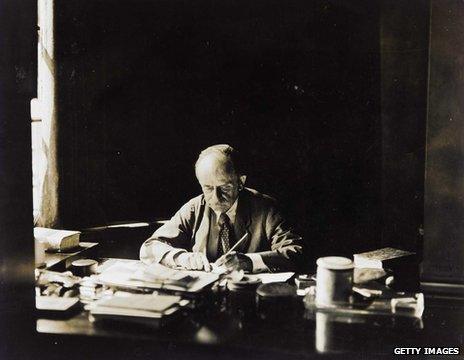

JM Barrie gave the rights to Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children

"Peter Pan has the same basic narrative that so many great children's classics share. The protagonists are often orphans: if possible, you kill off the parents on page one or the author finds some other way to push them to one side.

"Think of the Narnia books or The Wizard of Oz. Think of Harry Potter or some of the works of E Nesbit. The children have to overcome harsh realities and meet terrible monsters or whatever. Young readers are enthralled.

"So in Peter Pan the children are separated from their parents. It's a map of how to survive when you're young and vulnerable, and there's a hostile world out there. But in all these stories there's no way you're going to make it without companions and maybe some magic powers.

"You can change anything else in the story but even the most radical new version of Peter Pan would need to preserve two things. There's the idea of the children learning to cope without parents - that's the heart of the book and without it there's no story.

"And it would be a very brave director who did away with all the flying. Last year I went to an American version of Peter Pan which in some ways was a little flat and disappointing. But the moment Peter flew out above our heads, the entire theatre was in raptures."

The RSC's Wendy and Peter Pan is on until March in Stratford-upon-Avon.

- Published23 September 2013

- Published22 September 2012

- Published17 September 2012

- Published20 October 2011