Will theatre fans warm to Stephen Ward the musical?

- Published

Stephen Ward was one of the most controversial figures in 1960s Britain. He was at the centre of an extraordinary sex scandal that brought down the minister for war, John Profumo, destabilised a government and, in August 1963, led to his own suicide.

Now Andrew Lloyd Webber has written a musical about him - but will audiences find Stephen Ward sympathetic?

The life of Ward is complex and full of ambiguities, and Andrew Lloyd Webber says that's what made him want to put him on stage.

"I found this a fascinating story, once I realised I didn't want to write about the Profumo scandal as such," he says.

"Stephen Ward is the centre of our story and in the new show what happened to John Profumo doesn't really take up much stage time.

"There's a growing view that Stephen's death came after a complete mistrial. Huge pressure was put on the police to get a conviction. You may not approve of everything Stephen did but he wasn't a pimp, which is what he was accused of.

"It's a really interesting area of history to delve into and some people will be hearing it for the first time. So why shouldn't we do it as a musical?"

Sideline of history

For a younger generation, Ward stands on the sidelines of British history - vaguely recalled as the man involved 50 years ago in the downfall of senior Conservative politician John Profumo, who died in 2006.

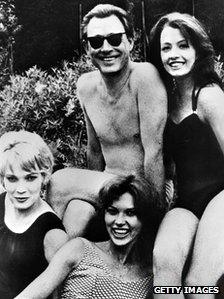

Ward with Christine Keeler (R) and her friend Penny Marshall (front).

He was a London osteopath who used his practice to make contacts with showbiz figures and high society.

"There's no doubt he was a skilled medical practitioner," says the academic Stephen Dorril, who has just revised the book he co-wrote about Ward. "Otherwise, people as varied as Winston Churchill and Ava Gardner wouldn't have turned to him for treatment."

"His work gave him an entree into the smart set and he relished that. If there was an element of the snob to him at times, that's what English society was like in those days.

"Initially his had been a very fusty, post-war world. The people he associated with were foreign royalty, figures in the film business now largely forgotten and various journalists of the day. And then he found ways to make himself useful to some of his male acquaintances, which had little to do with osteopathy."

Ward introduced selected male clients, and others he met through them, to attractive young women. Sometimes this led to sex.

"But what he did wasn't for money," Dorril says. "I think the best term for it would be social pimping. I imagine it amused him to see some of these relationships develop, or he enjoyed wielding a bit of influence in high places. But he wasn't procuring young women in the sense people usually mean."

Yet at the end of his life, to his horror, Ward found himself charged with living "wholly or in part on the earning of prostitution". By then his name was known worldwide and linked permanently to that of Britain's Minister for War, John Profumo.

Andrew Lloyd Webber was joined by Mandy Rice Davies (right), who played a role in the Profumo scandal, and Charlotte Blackledge (left), who plays her in the musical, for the show's launch

Ward lived some of the time in a house in the grounds of Cliveden, Lord Astor's grand Italianate home in Berkshire.

In July 1961, Ward invited the 19-year-old Christine Keeler to Cliveden and took her to a poolside party at the main house. Through him, she met Profumo and soon began an affair with him.

But Keeler was also involved with Yevgeni (Eugene) Ivanov, a naval attache at the Soviet embassy in London, whose real masters were Soviet Military Intelligence.

Accounts vary as to how far the Ivanov relationship went but, says Dorril, "certainly Christine Keeler saw him several times and Ivanov was a visitor to Stephen Ward's London house at a time when she was involved with Profumo".

Dorril says Ward already had connections to British intelligence. "He wasn't an agent but an asset at arm's length who might at some point become useful. It was a relationship MI5 more often had with journalists.

"Even now we don't really know if they encouraged Ward to befriend Ivanov, hoping the Russian could be lured into sexual indiscretion. Or was the connection between Ivanov and Keeler a chance encounter which complicated the affair with Profumo?"

'No impropriety'

The press had their suspicions but the Keeler-Profumo affair was unknown to the public until well after it was over.

In December 1962 Keeler's stormy relationship with club-owner Johnny Edgecombe (in fury he shot six times at the locked door of Ward's mews house in central London) gave journalists an excuse to dig into her background. An astonishing story started to unfold.

Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice Davies were mobbed when they attended Stephen Ward's trial

Profumo told Parliament there had been "no impropriety whatsoever" in his relationship with Keeler. Two months later he admitted he had lied to the House of Commons and his political career was finished.

In August 1963 Ward was prosecuted for living off immoral earnings. On the evening of the trial's final day he took an overdose at a friend's flat in Chelsea and died. An inquest found he had committed suicide.

In October, the then-Prime Minister Harold Macmillan stood down, partly as a result of the pressures the scandal had created in the country and within his party.

It's a fascinating tale, with some elements still not fully explained. But does it make a musical? The show's lyricist Don Black doesn't doubt it.

He says: "When someone comes to me with a project I always ask, 'Is it a fresh idea and will it work for audiences?' And soon I realised the answer to both those questions was yes.

"Just look at the subject matter. Chequebook-journalism and the role of a free press, the sexual morality of the rich and famous, celebrities who aren't quite what they seem, police corruption, the class system and social change. All those things resonate today.

"Lots of the ideas that people pitch to me are basically re-treads but there's never been a musical like this one.

"The more I learnt about Stephen the more I sympathised

"He may have led an unconventional life but really he did nothing wrong. I was in my 20s when he died so I remembered the basics. But reading about Stephen now I realise what a victim he was."

Stephen Ward opens at the Aldwych Theatre in London's West End on 19 December.

- Published30 September 2013

- Published20 May 2012

- Published10 May 2012