Buffy the Vampire Slayer: The legacy of the teen heroine

- Published

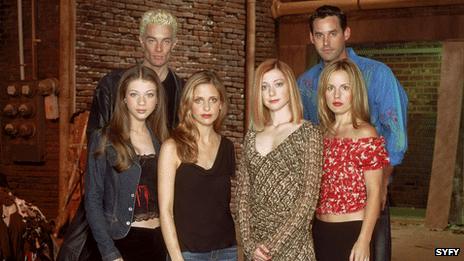

Sarah Michelle Geller (left) played Buffy Summers from 1996 to 2003

Ten years after the cult TV series was broadcast on the BBC, what is Buffy the Vampire Slayer's legacy and why there are so few "daughters of Buffy": strong and complex fictional creations, who aren't simply the sole female lead in a predominantly-male cast.

Believe it or not, it's 10 years now since the last episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer aired in the UK.

If it doesn't feel that long - and it doesn't - it's because the show was ahead of its time in so many ways: the quick-witted teen-speak which influenced conversation; the craze for stories about vampires who are in love with high school girls in a slightly disturbing way.

Creator Joss Whedon's perfect management of "season arc" plots revolutionised television and is still spoken of with awe and wonder by writers today.

And most importantly - but most disappointingly - Buffy still feels ahead of its time in its portrayal of women characters.

And it's because of my disappointment about the lack of "daughters of Buffy" I chose to make a Front Row special about Buffy the Vampire Slayer and her legacy.

Lagging behind

Buffy the Vampire Slayer was a small mid-season replacement show based on a terrible movie, which quickly outstripped its origins to become a cult hit and then a mainstream phenomenon. And in a way, Buffy's legacy is everywhere.

It was the first show to perfectly balance a "monster of the week" plot - in which a single problem is encountered and defeated in every episode, so that new viewers can easily get the gist - with a season-long "arc" plot around a scary "Big Bad" villain who takes the whole 22-episode season to be brought to book.

Everyone's doing this now, with varying levels of success; we can see it in everything from the new Doctor Who, Sherlock and Being Human to American shows like Sleepy Hollow and Fringe.

Buffy creator Joss Whedon once described the show as 'My So-Called Life meets The X-Files'

Buffy was also incredibly creative, playful television, weaving what might have been gimmicks - a musical episode, an almost-entirely-silent episode - seamlessly into the story in a way which has often been imitated but rarely equalled.

But in the crucial central aspect - the way the show dealt with its female characters - most television and movies are still lagging way behind Buffy's decade-old example.

"But no!" I hear you cry from across the land. "The strong female character is a very common figure in all sorts of media now, from women kicking ass in videogames to sassy wisecracking super heroines in outfits which show off their toned buttocks and muscular, um, breasts. Just look at how the movie posters show off how strong they are!"

Well, yes. Buffy was a "strong female character" in the sense she had super-strength and could push a stake through a vampire's breastbone with as little effort as most of us would expend pushing a toothpick into a festive canape.

But her strength wasn't just about that - and that's where so many so-called strong female characters fall down, even today.

For one thing, Buffy was written strongly - meaning she was a fully-rounded character, with weaknesses and vulnerabilities to go along with her super-powers.

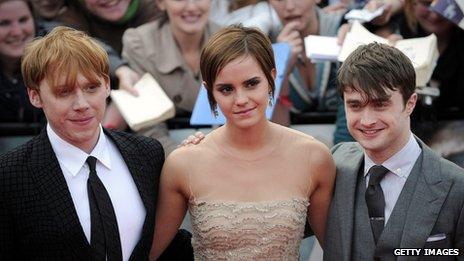

The main cast of Harry Potter features the typical grouping of two boys and a girl

Not only was she physically strong, her role in the drama was also central - unlike so many female characters, she wasn't primarily there to be a man's love interest, or a femme fatale.

She had relationships, she fell in love, had her heart broken, got dumped, and sent the love of her life to hell - well, who hasn't? - but those relationships weren't what defined her.

Contrast that with Twilight's Bella Swan, utterly subsumed by her relationships with men.

And equally importantly - she was surrounded by other strong, interesting, complex women.

What's astonishing even now is to look at the cast line-up of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Not just Buffy herself, but also best friend Willow the witch, Willow's girlfriend Tara, nemesis-come-wary-ally Cordelia, ex-demon Anya, mother-in-a-trying-situation Joyce and latterly, the mystically-created sister Dawn.

So often now, a "strong woman" in a TV show or a movie will be almost entirely isolated from other women - from Katniss Everdene trying to survive the Hunger Games to Sandra Bullock's character in Gravity, from Carrie Mathison in Homeland to Daenerys Targaryan in Game of Thrones - female friendship, let alone having conversations with several women, seems utterly impossible for many of today's female characters.

How do you write strong female characters?

When I raised this question with show creator - and now Hollywood director - Joss Whedon, he agreed perhaps the wrong lessons had been learned from Buffy's success.

"The romance and the supernatural and the lure of the vampire… all seemed to go over pretty well," he said.

"The self-actualised female who was in charge of things didn't land quite as solidly…. I, too, have been somewhat disappointed… it feels almost like a backlash - we want to inoculate ourselves against this by giving you everything [Buffy] had without the feminism."

Even its main cast of three friends, two women and a man - Buffy, Willow and Xander - was extraordinary.

As Jane Root, controller of BBC Two when Buffy aired and now founder and chief executive of production company Nutopia, pointed out to me when I interviewed her, the set-up for sci-fi or fantasy is most often still "two boys and a girl".

Think of Harry, Ron and Hermione, or Aidan, George and Annie in Being Human, or The Doctor, Rory and Amy in Doctor Who, or Walter, Peter and Olivia in Fringe.

What Buffy showed us is that having one strong female character per show - even if she's well-written, interesting and complex - just isn't enough. After all, you can't pass the Bechdel Test, external with just one woman in the cast.

When I first saw Buffy the Vampire Slayer, I naively thought it would spell the beginning of a new wave of television and movies - ones where the women characters could be written as well as the men, where women would take the lead as often as men and where they would be surrounded by many other female characters.

It hasn't happened yet. But I continue to hope that it will. And until we've made TV like that, Buffy will continue to seem new, fresh and revolutionary.

The Front Row special on Buffy the Vampire Slayer is on 26 December at 19:15 GMT on Radio 4.

- Published5 February 2013