Obituary: Denis Norden

- Published

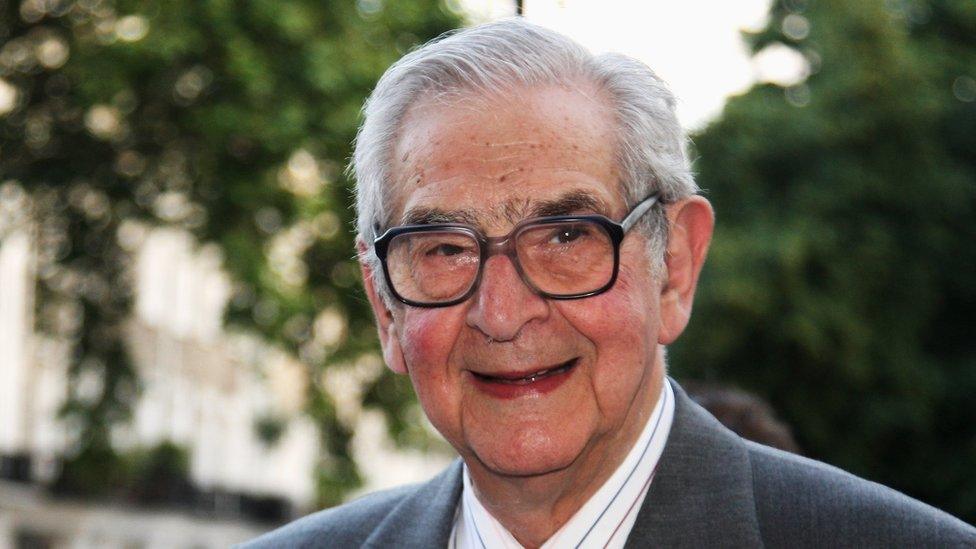

TV presenter and comedy writer Denis Norden has died aged 96

One day, three young comics went to find some lights for a show they were doing.

They were entertaining the RAF in northern Germany and had been told they would find what they needed at a nearby camp which had recently been liberated.

The camp was called Bergen-Belsen. None of them knew what evil had happened there.

"We didn't know what to expect," recalled Denis Norden half a century later. "We had not heard a word about it."

Norden and his two friends, Ron Rich and Eric Sykes, dumped the lights. They went straight back to their own camp and picked up whatever spare food they could find.

"Appalled, aghast, repelled - it is difficult to find words to express how we felt as we looked upon the degradation of some of the inmates not yet repatriated," he said.

Seventy thousand people had died in Bergen-Belsen, most of them by starvation. "As far as I could see, all these pitiable wrecks had one thing in common. None of them was standing."

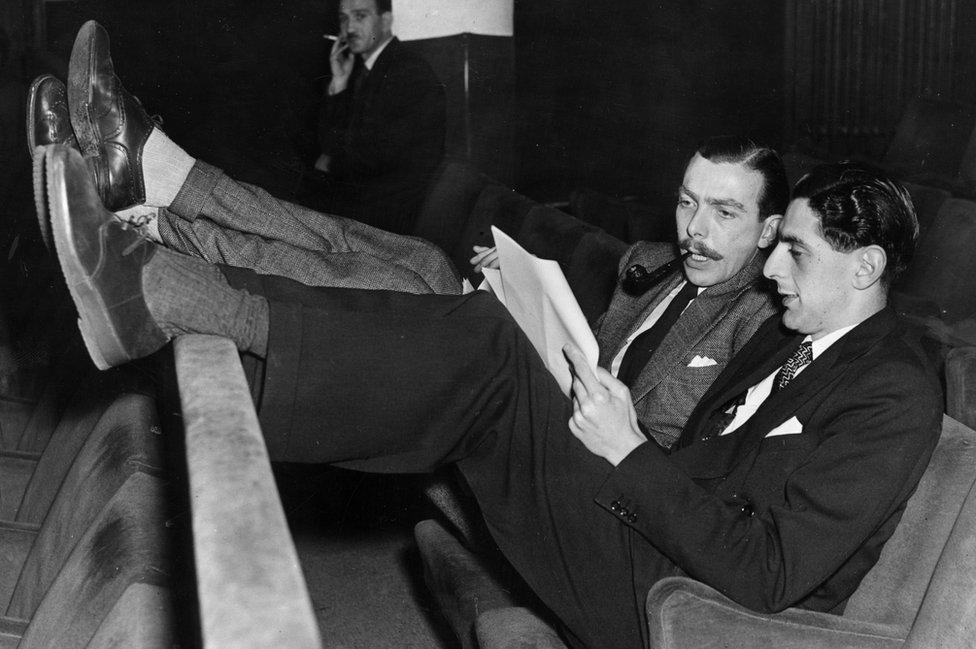

Denis Norden with his old army friend, Eric Sykes. In 1945, they were first-hand witnesses to the appalling conditions in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany. Norden gave a moving interview about the experience to BBC radio many years later.

Norden was deeply moved by what he had just seen. Nor could he bear the sight of hungry German children hanging round outside the RAF base.

"After seeing the camp, you could in theory hold it against the Germans, but you couldn't hold it against these German kids," he told the BBC. They handed out their own rations to dozens of small, eager hands.

It was a shattering experience for the young Norden, who then had the near impossible task of putting it all out of his mind, walking on stage and making men laugh.

Youthful ambition

Denis Mostyn Norden was born into a Jewish family in Hackney, East London, on 6 February 1922.

He was academic and bookish, winning a scholarship to the City of London School. The novelist Kingsley Amis was a fellow pupil.

"I was very tall, very skinny and always had my nose in a book", he remembered. He also had a burning desire for adventure.

Denis Norden with scriptwriting partner, Frank Muir. The two men wrote thousands of hours of comedy for the BBC. Catchphrases like "trouble at t'mill" and "Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells" are still in the language.

He wrote to the Daily Express at the age of 16, and asked if he could accompany the foreign correspondent to the civil war in Spain. To his amazement the journalist agreed, but his spoilsport parents put their foot down. So he turned his mind to another ambition.

"I'd seen a photo in Life magazine of two Hollywood screenwriters beside a swimming pool being served drinks by two blondes and I couldn't imagine a better life than that," he said.

To find out what audiences wanted, he left school and - at the age of 18 - became Britain's youngest cinema manager.

When the war intervened, he became an RAF wireless operator, teamed up with Eric Sykes and branched out into performing for the troops.

Demobbed, he started writing for radio and found himself teamed up with fellow aspiring comic, Frank Muir.

The man who brought them together was Ted Kavanagh, producer of the wartime hit It's That Man Again, universally known as ITMA.

He asked if they would be averse to writing together. "Not a whit averse," they replied simultaneously.

The fact that they spontaneously used the same arcane phrase showed how their minds could work as one. They would become one of the most successful comedy writing partnerships in British history.

Between them they wrote three hundred episodes of Take It From Here with Jimmy Edwards and, later, June Whitfield. The series lasted 11 years and created such memorable characters as The Glums. Their catchphrases like "Trouble at t'mill" and "Disgusted of Tunbridge Wells" are still part of the language.

There were collaborations with Peter Sellers, and other hits including Bedtime with Braden and the television series Whacko, also starring Jimmy Edwards.

Elizabeth Fraser and Jimmy Edwards in Whacko, a weekly comedy written by Denis Norden and Frank Muir for the BBC

The pair were also responsible for some of the most memorable Carry On lines - including "Infamy, infamy, they've all got it in for me" - which was borrowed with their permission.

Golden Globe nomination

In the early 1960s, Norden and Muir came up with the television legal comedy Brothers in Law, starring a young Richard Briers.

Frank Muir and Denis Norden at work. Their full-time writing partnership came to an end without rancour when Muir took a job in BBC management.

They were given a three-year contract as BBC consultants and scriptwriters. Muir loved it but Norden found the corporation stifling.

"I wasn't much good at it and didn't like it," he said. "At the end, I just wanted to leave and be independent again."

The partnership ended amicably when Muir opted to stay with the BBC full time. They did, occasionally, work together - appearing on quiz programmes like My Word and My Music. But, for the first time in 20 years, Norden was without a full-time writing partner.

"When you're on your own, there is that terrifying possibility that you may be the only person on the planet who thinks it's funny - and you have no way of finding out," he said.

So great was Norden's need for reassurance that he would hand the pages of his scripts to a secretary in another office and then creep back and listen outside her door hoping to hear chuckles.

"Then after that came word processors, and it's hard to make them laugh."

Frank Muir and Denis Norden alongside Katie Boyle on The Name's The Same - the pair became regulars on TV panel shows

Norden hadn't forgotten his childhood ambition to write for Hollywood. He co-scripted the screenplay for the Golden Globe-nominated Buona Sera, Mrs Campbell starring Gina Lollobrigida, but it was as a performer that he became better known.

Nervous

In 1977, he got chatting to Paul Smith, the future producer of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, in the canteen at London Weekend Television. Over lunch, they were giggling about the famous Blue Peter clip where an elephant proved the old adage about never working with children or animals.

One of them wondered aloud if you could do a whole show based on funny outtakes. They rang Michael Grade, LWT's director of programmes, and within half an hour they had a commission, a budget and even a title - It'll Be Alright on the Night. The show ran for 29 years.

"Well it's not the best title," Norden recalled thinking as they left Michael Grade's office. "But we'd better go with it."

At first, news programmes refused to release their howlers - but eventually relented. Actors and producers were also wary, but discovered that - with repeat fees - they could often get paid more for getting it wrong than getting it right.

Norden masterminded the whole operation, choosing the clips, writing the scripts and delivering them, clipboard in hand, in his inimitable, avuncular style.

"It's like running a farm where the manure is worth more than the cattle," he would joke.

The show was copied around the world and spawned many a clone, even before YouTube made pratfalls a cottage industry.

"One of the necessities for a good clip is that you can't second-guess it. The trouble with a lot of blooper shows nowadays is that you can see what's coming," he would lament.

His favourite clip was of a hapless regional TV reporter offering a tray of delicacies to the great British public out shopping. "Are you feeling peckish?" asked the journalist. "No, I'm Turkish," came the confused reply.

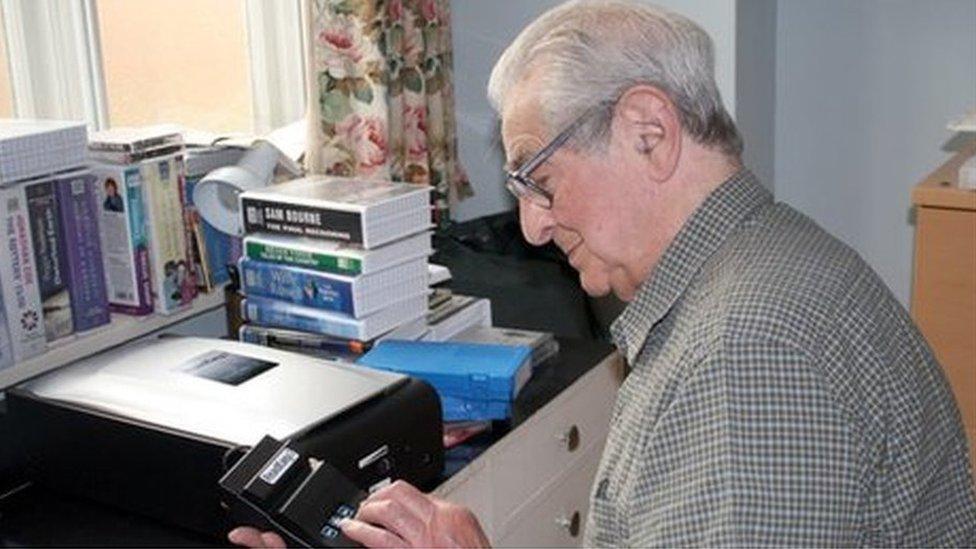

Norden was still working in his eighties despite losing his eyesight. He wrote his autobiography on a special computer which could read back what he had written

He continued working until failing eyesight forced him to retire in 2006. A haemorrhage at the back of his eye meant he could no longer see the TV clips. He may also have suffered from macular degeneration, although experts could never really tell.

Naturally rather shy, Denis Norden never saw himself as a performer. A marvellous wit and raconteur, in his own mind he was simply a "writer who keeps getting wheeled out".

In truth, he was far happier at home than on stage - with his two children and his wife Avril, whom he married in 1943.

For years, he resisted writing an autobiography, claiming that Frank Muir had pretty much covered everything in his own memoir. A book called The Bits Frank Left Out would be disappointingly brief, he said.

But, in his eighties and by now partially sighted, he changed his mind. He used a special computer which read back what he had typed, although it was a long and painful process.

What shines through is his love of working with other comedians and the challenge of making other people funny. And, looking back over more than 70 years in comedy, he counted himself supremely fortunate to have worked at the time that he did.

"We not only lived through the golden age of so many forms of popular entertainment," he wrote. "We were present at the birth of them, enjoyed their heyday and were there to mourn their passing."