The village where art is put to work

- Published

Laure Prouvost's Turner-winning installation has been recreated in Coniston

Two months ago, an installation by artist Laure Prouvost won the Turner Prize. Now it has gone on show in a small museum in Coniston, Cumbria, as part of an attempt to use art to reinvigorate village life.

In Coniston, there are no fashionable galleries. But locals are used to having contemporary artists hanging around.

Laure Prouvost's Turner-winning work Wantee was made in Coniston with the help of the local youth club, and it has just returned to the village in an attempt to boost the profile and visitor numbers of its Ruskin Museum.

The work, which centres on a 14-minute video about the artist's fictional grandfather, was filmed in a wooden hut in Cumbria before going on to be shown at Tate Britain, where it was picked out by the Turner judges.

Laure Prouvost was awarded the Turner Prize in Londonderry in December

Prouvost enlisted Coniston youth club to help create her installation

The artist describes it as "a collaboration" with local residents. "When we built the shed, for example, we had the youth club come in to help, and they helped us making sculptures," she says.

"It was made in Coniston so it's really nice that it comes back and everyone who's been involved and part of it can look at what they've made."

Wantee was co-commissioned by Grizedale Arts, a Coniston-based group with a big reputation in the art world.

Grizedale has previously enlisted another Turner-nominated artist to redesign the village library and persuaded The Kinks singer Ray Davies to write a school play.

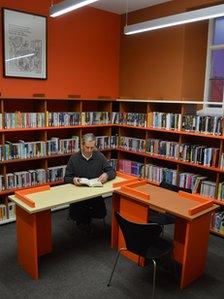

Turner Prize nominee Liam Gillick redesigned the village library

Grizedale's other projects include running the youth club, setting up a shop for local crafts and breathing life into Coniston's harvest festival.

This week, four artists have arrived to help design new products for the village to make and sell, with the aim of aiding the local economy.

The group's artistic influence has even been felt at the annual agricultural show. "The village veg show was just dying on its feet because it had always gone on in the same way," says Anne Hall, a parish and district councillor. "They've given a new momentum to that.

"People are beginning to realise that art isn't just pictures in a gallery."

A few years ago, many villagers regarded Grizedale as "the people who do the weird art stuff", says its deputy director Alistair Hudson.

But they are trying to prove that art is "something ordinary", rather than only belonging in metropolitan galleries.

"The old idea of art, which has been around for millennia, is that art as part of our everyday mechanisms for dealing with life and making things work," Mr Hudson says.

"You apply art - or artfulness - to everyday living. What we've tried to do in the village is demonstrate how art might come up with solutions or answers or suggestions for how things might work in village life.

"Art or artfulness or creativity then becomes part of this everyday process."

Grizedale Arts set up the Honest Shop to sell local produce and crafts

So Grizedale took over the youth club in 2012 and now enlists the members in regular art projects. It even involved the youth club in a project for the annual extravaganza of modern art excess, the Frieze Art Fair, in London in 2012.

On seeing the Coniston contingent, one mover and/or shaker from the capital's art cognoscenti thought the village was an artist's elaborate creation. "They thought it was a story made up for Frieze," Mr Hudson recalls. "They didn't believe it was a real place."

Back in Coniston, Grizedale runs the Honest Shop, in which locals sell wares ranging from cakes to wood carvings. "The system and the look of it was all designed as a product of art thinking," Mr Hudson says. "But it is actually working in the world."

And this week, four artists are brainstorming with local businesses to devise new goods that the village can sell and export.

"Some might work and some might not," Mr Hudson says. "It might be something that somebody who does woodcarving can make, or somebody who does baking can make. It's developing small scale businesses and enterprises."

Turner-nominated Liam Gillick fashioned new "minimal and utilitarian crate-shelves" for the library, while Coniston's harvest festival was transformed into an elaborate communal meal after Grizedale was asked to overhaul the staid traditional ceremony.

"We asked people to bring excess produce and spent a day cooking a big meal, dressed the table nicely, made it look great, feel nice, got artists to write the menus, thought about the plates, the cups, the whole aesthetics, so it was a wonderful experience," Mr Hudson says.

Which is all very well. They may be good at creative thinking, but it is not really art, is it?

Mr Hudson argues that Grizedale (among others) is trying to return to an era when art was embedded in real life, before the art market took off and made it the plaything of a rich elite.

"Art is a competency," he says. "It's a way of thinking. It's a way of doing that you apply to life. It's not something separate."

Controversial ideas

Grizedale's methods have not been embraced by everybody in the village, though. "There are things we do that are contentious," Mr Hudson admits.

"Some people in the village don't like what we do. It's complicated and difficult and you have to keep chipping away and responding to it as you go along."

Coniston is lucky (or perhaps unlucky) to have an arts organisation with such expertise, contacts and £166,000 in annual Arts Council funding on its doorstep.

Similar resources and creativity will not be available to most other communities. But Mr Hudson believes there are lessons that can be applied elsewhere.

"I don't think you can copy this because everywhere's different," he says. "But you can certainly apply the same methodologies and tactics and ways of working.

"It's not new. It may not even be art. But anything can be art. As we know."

- Published4 December 2013

- Published3 December 2013

- Published7 September 2012

- Published17 December 2011