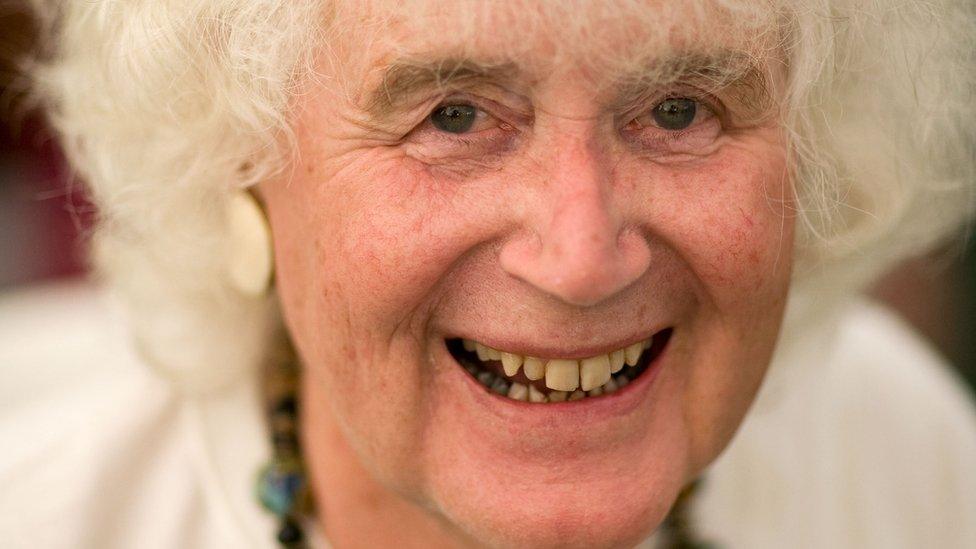

Obituary: Jan Morris, a poet of time, place and self

- Published

Jan Morris, who has died at the age of 94, was one the finest writers the UK has produced in the post-war era.

Her life story was crammed with romance, discovery and adventure. She was a soldier, an award-winning journalist, a novelist and - as a travel writer - became a poet of time and place.

She was also known as a pioneer in her personal life, as one of the first high-profile figures to change gender.

Born 2 October 1926 in Somerset, it was while sitting under the family's piano - at the age of three or four - that Morris made a decision. Feeling "wrongly equipped" as a boy, there was only one conclusion. Morris should have been a girl.

Morris attended Lancing College in West Sussex and then the cathedral choir school at Christ Church in Oxford, attending lessons in gorgeous "fluttering white gowns". "Oxford made me," she later wrote.

The heady mixture of High Anglican ceremony and the city's architectural majesty sensitised Morris to an aesthetic that was to influence her as both a writer and a human being.

Oxford was a city that had a big influence on Jan Morris

As a teenager, training as a newspaper reporter in Bristol involved interviewing the victims of bombing raids at the height of the Second World War.

Morris tried to join the Navy but was ruled out by colour-blindness, instead joining the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers.

A spell at Sandhurst was followed by a posting as an intelligence officer that led to stints in Italy and Palestine by way of two more cities that came to be inspirations: Venice and Trieste.

Demobbed in 1949, Morris returned to Christ Church to read English, and seized the opportunity of a 12-month fellowship at the University of Chicago to visit every state of the union.

The result was a first book, Coast to Coast. "I love the idea of America," she later wrote. "It has let itself down very badly since in many ways, but that doesn't mean to say I don't admire and love the core values."

In the same year, Morris married Elizabeth Tuckniss, the daughter of a tea planter. It was, they both recalled, love at first sight - and a partnership that would produce five children and last for 70 years.

Everest scoop

Upon graduating, Morris indulged a fascination with the Arab world by taking a job at a news agency in Cairo. That experience eventually led to a job at the Times.

In 1953, Morris brought the newspaper a world exclusive, travelling with Edmund Hillary as far as the base camp on Everest to witness the historic attempt on the summit.

Morris greets Edmund Hillary on his return from the summit of Mount Everest

It was a physically arduous assignment. "I was no climber, was not particularly interested in mountaineering. I was there merely as a reporter."

When Hillary and Tenzing Norgay returned in triumph, The Times had exclusive access to the expedition - but the reporter was terrified that someone else might break the news first.

Morris sent a coded message from a telegraph station: "Snow conditions bad stop advanced base abandoned yesterday stop awaiting improvement." Back in the newsroom, they knew what it meant.

The news was famously splashed on the day of the Queen's coronation. The world's highest mountain had been conquered and a new Elizabethan age had begun.

Suez shockwaves

In 1956, Morris left the Times - unable to support the newspaper's editorial line in the Suez crisis. After joining the Manchester Guardian, as it was still called, the journalist set out to witness the looming conflict first-hand.

The reports Morris sent from the Suez crisis caused great difficulty for the British government

Allegations that Britain and France had secretly persuaded Israel to launch an invasion of Egypt had been hotly denied by all three countries. Morris discovered evidence that this was a pack of lies designed to give the two European powers an excuse to intervene and re-take the all-important canal.

Morris witnessed the fighting in the Negev desert and canal zone before flying to Cyprus to file a dispatch and escape Israeli censorship. While waiting for a flight, the writer struck up conversation with French pilots who said they had played a pivotal role in the attack.

"They told me quite frankly that they had been in action in support of the Israelis during the Negev fighting and had used napalm," Morris later recalled. British pilots, they claimed, had also been involved.

The Manchester Guardian went with the story. It sent shockwaves through the British establishment and shamed both nations into withdrawing their forces. It was an incendiary revelation that caused huge embarrassment to Prime Minister Anthony Eden. A few months later, he resigned.

A writer who travels

In the 1960s, Morris left journalism, preferring to be simply known as a "writer who travels" rather than a "travel writer".

Morris wrote about places that were inspirational - Oxford, Venice, Spain and the Arab world - with the dream of capturing the history, style, spirit and challenges facing every major city in the world.

The book Morris wrote on Venice in 1960 remained in print for the next seven decades

Most dear of all was the trilogy on the history of the British Empire: Pax Britannica. Morris described it as "the intellectual and artistic centre-piece of my life". Later, the author would reject the suggestion of being too kind to this period of history.

"There was a whole generation of very decent people, many of whom were genuinely devoted to the welfare of their subject peoples," she later said. However, she conceded, the end was a mess.

In the same year, Morris began taking female hormones in the first stage of the life-long ambition to become a woman. Elizabeth, who had always known of her husband's conviction, was supportive.

Morris had a high public profile and the publicity that surrounded her decision was stressful. As same-sex marriages were not then possible, they were required to get divorced. But as a family, they stayed together and remained tight-knit.

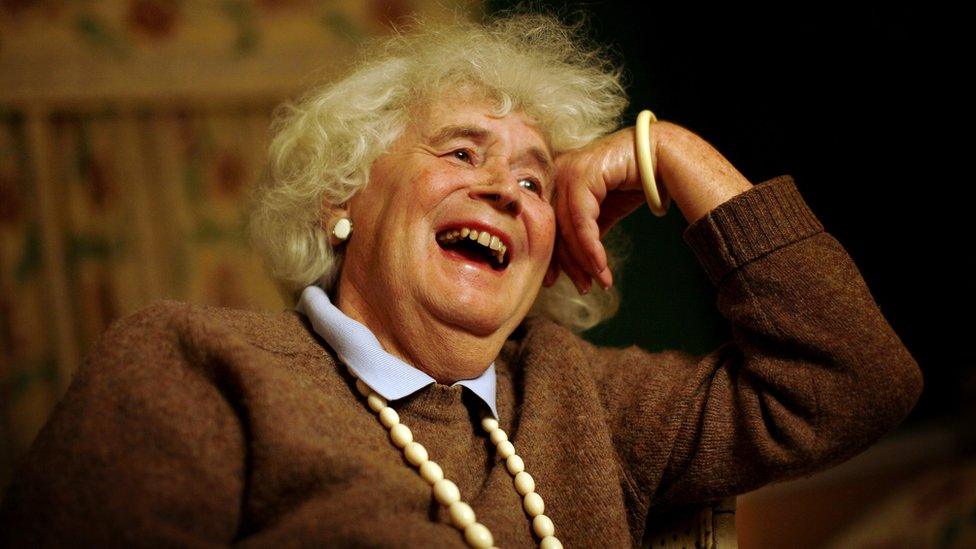

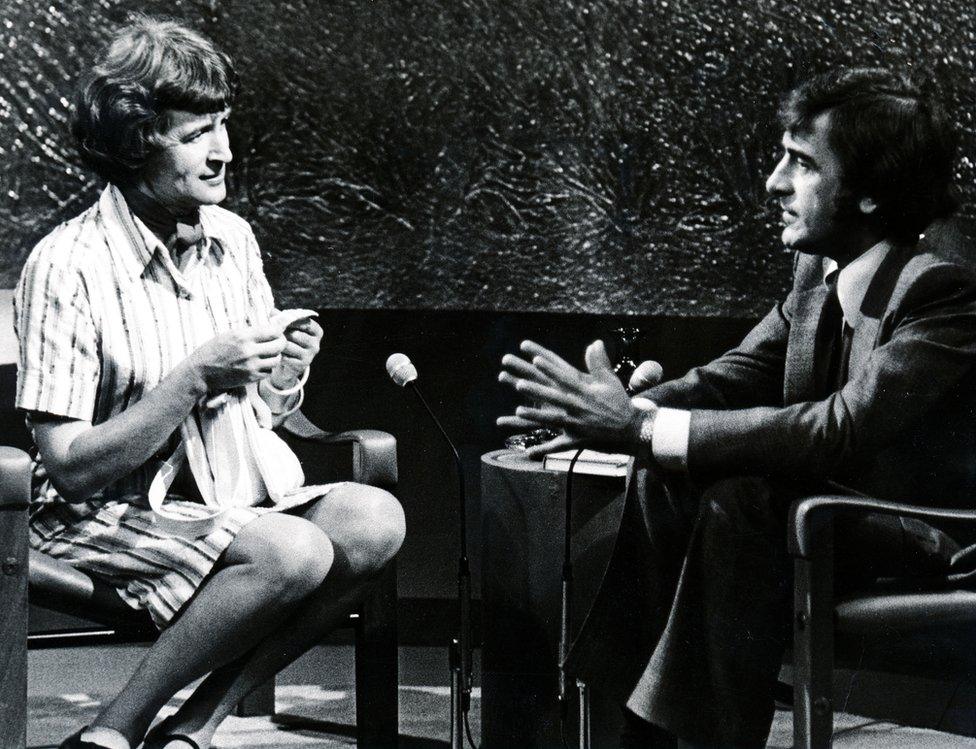

Jan Morris, pictured in 1974, was legally required to divorce her wife, Elizabeth, but the couple remained together

Morris wrote about the process in her worldwide bestseller Conundrum - published in 1974. It describes the clinic in Casablanca where she had surgery and her subsequent adjustment to life as a woman with a female partner. She was generous to those who found it awkward and "the kindly incomprehension of sailors and old ladies".

She was forced to ignore warnings from doctors that the procedure could change her personality and even affect her ability to write. The book was the first to be published under the name Jan. There was a sense in which all that travelling was a symptom of forces beyond her control. It was "an outer expression of my inner journey".

The couple moved to a remote corner of north-west Wales. Jan embraced her father's Welsh identity - becoming a convinced nationalist - and continued to write. Her output was prodigious. In all, she wrote more than 40 books - so many that she was often a little hazy about the exact number.

There were works on places she had visited, essays, memoirs and some well-received novels. One work remains unpublished because she did not want it made public until she died. "It's at the publisher's waiting for me to kick the bucket," she breezily told one reporter.

Morris published more than 40 books - although one remains with her publisher with instructions to be published posthumously

On Oxford - the first city to inspire her - she wrote: "The island character of England is waning as the wider civilization of the West takes over. Soon it will survive only in the history books: but we are not too late, and Oxford stands there still to remind us of its faults and virtues - courageous, arrogant, generous, ornate, pungent, smug and funny."

And on Venice - perhaps her most celebrated work - she recalled the "smell of her mud, incense, fish, age, filth and velvet" and predicted that "wherever you go in life you will feel somewhere over your shoulder, a pink castellated, shimmering presence, the domes and riggings and crooked pinnacles".

Her biographer and agent, Derek Johns, described what he thought made her writing so distinctive. "She involves the reader," he wrote, "while she remains unobtrusively present herself; who uses the particular to illustrate the general, and scatters grace notes here and there like benefactions. She is a watcher, usually alone, seldom lonely, alert to everything around her."

In 2018 - by now in her tenth decade - Jan Morris published In My Mind's Eye, a personal work collecting the musings of her everyday life.

The world had become kinder to people who had changed their sex, she told one journalist. Kindness and marmalade were her two essentials in life.

She was still living with Elizabeth - with whom she had entered a civil partnership - although the "subtle demon of our time, dementia, is coming between us", she wrote.

As far as death was concerned, though, they had prepared for it. As a writer, Jan had chosen the words for their eventual headstone with some care. "Here are two friends," it will say, "at the end of one life."

- Published20 November 2020