The opera singer who changed the civil rights movement

- Published

Marian Anderson pictured in her garden at her Philadelphia home, which has now become a museum

Seventy-five years ago this week a concert took place in Washington DC that many people see as an important precursor to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

It featured the classical contralto Marian Anderson, praised as one of the great American singers of the era.

When the colour of her skin excluded her from a major concert hall, Anderson, who insisted she had no interest in being a social campaigner, became the centre of a fierce political storm.

Anderson owned 762 South Martin Street, Philadelphia, for most of her life. It has now been restored as a museum of her life and remarkable career.

In 1998 Philadelphia officially renamed the street Marian Anderson Way, a testament to the woman who occupied the pleasant but modest property as a remarkable presence in city life.

Anderson was a rather private person. Yet she was a superb performer, whether in the operatic repertoire or performing spirituals.

She always said that everything she wanted to say was in her art. Yet three quarters of a century ago she found herself in the middle of a very public debate in America's capital about segregation and racial politics.

Anderson rehearsing with pianist Franco Rupp in 1949 for a concert performance at Covent Garden

Anderson had been born in Philadelphia in 1897. Her parents, far from wealthy, attended a Baptist church and it was there that the youngster's vocal ability became obvious.

As a child the musician Blanche Burton Lyles knew Anderson. After the singer's death she established the museum in her honour.

"Marian was very gracious and genteel. She was so unassuming. She had no interest in politics but here in Philadelphia she became a great figure. When you listen to her recordings you hear a real depth.

"Sometimes at the end of her concerts there was total silence, which would have worried some artists. But it came from the audience's reverence for her spirituality."

After high school, Anderson applied to study at the Philadelphia Music Academy, an all-white institution. She was turned away not because she lacked talent or potential as a singer but because of her colour.

'Crushed and disappointed'

Speaking to the BBC in 1984 she explained how she reacted at the time. "I was terribly crushed, terribly disappointed. The young lady who told me seemed to take so much pleasure in telling me. Since I was terribly naive, I felt that a person connected with music could not have the kind of attitude she had."

Anderson instead studied privately, supported financially by the local community. From the mid-1920s her reputation grew: the purity of her tone was much admired.

But to build a top-level career she needed to go abroad. Anderson made her London debut in 1930 and found further acclaim in Salzburg and Moscow. She was also a favourite of the Finnish composer Sibelius.

Anderson paid another visit to London in 1952, flying in to what is now Heathrow after singing in Sweden

The incident that gave her a place in American social history came in 1939.

She and her agent Sol Hurok decided she was ready to sing in Constitution Hall, then regarded as Washington's main venue for classical music (a position since ceded to the Kennedy Center). The hall belonged to the Daughters of the American Revolution.

The DAR is a long-established body for women who "can prove lineal descent from a patriot of the American revolution". In 1939 that definition was held to exclude anyone who was black.

The DAR today is eager to point out that Anderson went on to perform at Constitution Hall in later life. The body has long ago apologised for its former policies and this weekend has a concert in Washington in the singer's honour hosted by Jessye Norman.

But 75 years ago Washington DC was a segregated city and all protests by fellow artists in support of Anderson were in vain.

But then something happened that shook the DAR to its core. America's first lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her membership in protest at how the singer had been treated.

Burton Lyles is sure Anderson must have been horrified to find herself in the eye of the storm. "Life for her was not about politics. I remember ever after she said very little about what had happened in 1939."

Anderson, who sang at John Kennedy's inauguration, attended a Washington meeting in 1961 for a foundation against world hunger with the president (centre), German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer (second right), Senator George McGovern and Mrs Woodrow Wilson

But in her 1984 interview, Anderson made clear she knew little in advance of the open-air concert organised in place of the one that did not happen in Constitution Hall.

The plan was mainly the work of Howard University in Washington, of Eleanor Roosevelt herself and of Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes.

Ickes had been a key architect of President Roosevelt's New Deal and his right-hand man on domestic politics. The fact that Ickes introduced Anderson made clear how disapproving the White House had been of the DAR's policy.

Ickes began his speech by saying: "In this great auditorium under the sky, all of us are free. When God gave us this wonderful outdoors, and the Sun, the Moon and the stars, he made no distinction of race or creed or colour."

Newsreel of Anderson's performance 75 years ago gives no sign of any nerves from her. She opens with a magnificent and moving version of My Country 'Tis of Thee, America's alternative national anthem.

Was Anderson as entirely uninterested in politics as she always said? Not generally a very demonstrative singer, she emphasised the word "liberty" in the lyric. The crowd of 75,000 applauded warmly after the song's end - "Land where my fathers died... From ev'ry mountainside - Let freedom ring!"

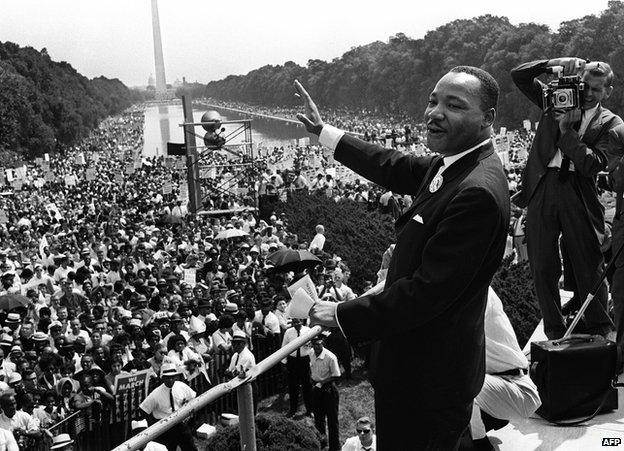

Anderson sang at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in which Martin Luther King made his famous I Have a Dream speech

In 1955 Anderson became the first African-American to sing in an opera at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. And in 1963 she sang as part of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in which Martin Luther King made his famous I Have a Dream speech. She sang, again, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

She had been supposed to sing the national anthem to begin the whole event, but missed the slot. Instead she sang one of her beloved spirituals.

Twenty-four years on from the events of 1939, it would have been unthinkable to have a march for civil rights in Washington without her.

Marian Anderson died, after a long retirement, in 1993.

- Published26 August 2013

- Published31 January 2012