Damon Albarn on life, elephants and his love of gospel music

- Published

The singer visited his old childhood homes in London and Essex while writing the album

Damon Albarn never intended to make a solo album.

He was perfectly happy with Blur and Gorillaz, or composing operas based on the Chinese pentatonic scale, until XL Records boss Richard Russell intervened.

"He turned round and said, 'I would like to produce you,'" says Albarn, recalling a conversation that took place after the pair co-produced Bobby Womack's 2012 comeback The Bravest Man in the Universe.

"It was a slightly strange thing to say, considering that our relationship was based on us both being producers together. So there was a moment of, 'Really? Well, blimey. That means I've got to…'

"But I didn't really know what that was going to entail or involve, you know?"

To begin with, Albarn handed over more than 60 songs to Russell - demos and musical fragments he had collected over the years. "But the funny thing is, we hardly used any of them," he says.

Instead, the singer jumped on the Central Line, went back to his childhood home in Leytonstone, east London, and hit on a rich seam of inspiration.

If you watched BBC Two's Culture Show in February, you may have seen Albarn visiting those same old haunts, going misty-eyed over sweet shops, dustbins and church halls.

He also stopped by Hollow Ponds at the top of the Lea Valley, where, as a child, he swam in the open air during the 1976 heatwave.

Albarn revisited Hollow Ponds, one of the few areas in London with an uninterrupted view of the city, in 2013

The scene turned into a song, also called Hollow Ponds. It samples the Central Line and contains snapshots of that "eight year old in swimming trunks" through his school days to pop stardom and adulthood.

It also set the tone for the album, Everyday Robots, a wistful series of reflections from a family man in his 40s.

But whatever you do, do not call it nostalgic.

"I don't know if it was nostalgia," Albarn protests. "It was a journey I chose to re-trace, really, and see if I could learn something about myself.

"I found that, not surprisingly, there was an awful lot of stuff.

"The tricky thing was distilling enough of it into song, as opposed to autobiography - which is a very different way of doing the same thing."

"I thought of it as, how do you take big events and put them into verse?"

The result is his most intimate and revealing album to date. Low-key and textured, it is peppered with domestic detail and a recurring theme of alienation.

"I always keep office hours," says Albarn. "The idea of not being at home at night appals me."

"I had a dream you were leaving," he sings repeatedly on The Selfish Giant, a sad but familiar story of partners who have lost their spark.

"It's hard to be a lover when the TV's on and there's nothing in your eyes."

By his own admission, the latter lyric was especially hard to record.

"It's quite a strong line," he says. "At the very moment when I was getting ready to do my thing as a singer, I was like, 'Oh, I'm not sure about that.'"

Yet every time he threatened to put up his defences, Russell would coax him into opening up.

"There were moments where I'd go, 'I think that's a bit too close to the knuckle', and that's when Richard would step in and say, 'No, that's a really good line, you've got to keep that.'"

'A gentle form of sedation'

It makes you wonder what discussions they had over You and Me, a song that briefly touches on Albarn's Britpop-era heroin addiction. "Tinfoil and a lighter," he sings. "Five days on, two days off."

The lyrics prompted a media storm after Albarn, speaking to Q Magazine, described heroin as "incredibly productive for me".

The singer has since stressed that addiction was "brutal experience" and "nothing that I would recommend".

"I was extremely lucky," says Albarn of his heroin experience. "I found my way out of it a long time ago."

Clean now for more than a decade, the narcotic that concerns him most on Everyday Robots is technology.

The title track documents commuters "stricken in a state of sleep" by their phones, while Lonely Press Play frets that the infinite distractions in the palms of our hands allow us to suppress our emotions.

"It's a form of gentle sedation," Albarn says.

"I've always opted to have a very old-fashioned phone. There's no internet on my phone. You can't put lots of smiley faces on my phone. It's a very boring, monochrome Nokia.

"But I do have an iPad, which is a very different beast entirely," says the singer - who composed parts of the last Gorillaz album, Plastic Beach, using the tablet device.

"I love it because I can be creative with it," he says. "That's the key."

"When we're doing something creative, technology seems benign. But when we're doing nothing with it - and it seems to be doing a lot more with us - that's when it starts to become terrifying."

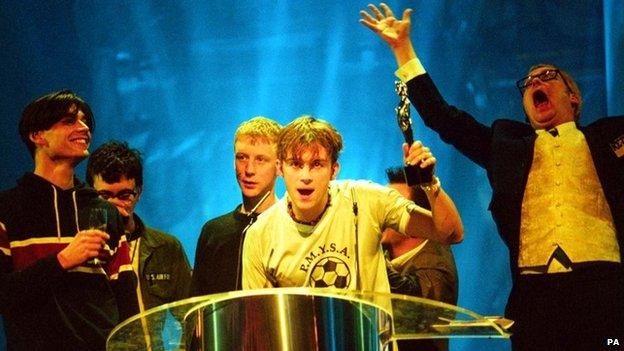

Blur scooped four Brit awards in 1995, thanks to their breakthrough album, Parklife

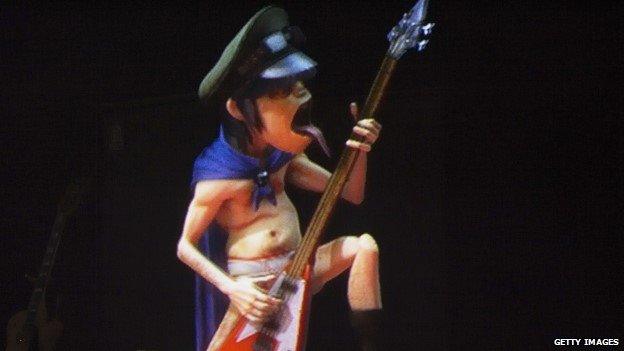

Early Gorillaz shows saw Albarn shun the limelight, while projected cartoons played the part of the band

Albarn previewed Everyday Robots live on 6 Music, saying: "It genuinely is a nice place for musicians"

Appropriately, electronics are kept to a minimum on Everyday Robots. The record is largely piano-led, pushing Albarn's voice to the foreground, and coloured with ambient sounds, trickling beats and exotic string arrangements.

The only time the record sheds its air of melancholy is on the jaunty Mr Tembo, written for an orphaned elephant Albarn met in Mkomazi, Tanzania. (The elephant responded by defecating, he says.)

It is the only song to survive from the original 60 demos he gave to Richard Russell, with an ebullient melody brought to life by The Pentecostal City Mission Church Choir, from Albarn's childhood church in Leytonstone.

"I love gospel music," the singer says. "I've loved it all my life. Whether it was listening to my parents' Mahalia Jackson albums or standing outside the London City Mission Church on a Sunday.

"I love all forms of religious music. It's the music I choose to listen to if I'm listening privately to music. Anything from Georgian orthodox choir music to Moroccan Sufi trance music to South Korean shamanistic music.

"You name it - if it is fit for the purpose of a spiritual connection, I love it."

Spirituality is exactly what Albarn hopes to achieve with Everyday Robots. His desire is that listeners will feel a personal connection to the lyrics, in a way they never could with the "Oi!" of Parklife.

"That's what can happen if you do something that is completely of yourself," he reckons.

"People find things in that because, at the end of the day, our experiences aren't really that different, are they?"

Everyday Robots is out now on Parlophone/XL Records.

- Published26 April 2014

- Published1 March 2014

- Published24 March 2013

- Published14 November 2012

- Published3 July 2012

- Published8 April 2012