ENO unveils new take on Oedipus tragedy

- Published

Roland Wood (l) recovered just in time for the opening night

It's no mean feat, bringing a brand new opera into the world. At a final dress rehearsal of Julian Anderson's Thebans at the English National Opera (ENO), just two days before the curtain went up on its world premiere, lead baritone Roland Wood had to mime the part of Oedipus.

He was recovering from a throat infection, and so for the final run-through, his part was sung by a stand-in, offstage left. A second cast member had also been struck by illness, and was testing her voice for the first time in days.

Such things are common hurdles when it comes to staging an opera. But it's fitting that this particular birth should have had its fair share of difficulties.

Anderson's new piece tells the story of one of history's most troubled families. With a libretto by Frank McGuinness, who had a hit with his 2008 stage version, it's an adaptation of the story of Oedipus, who famously murdered his father and married his mother.

The opera was described as "dazzling" by Guardian critic Guy Dammann

The composer sees it as a family tragedy in which the unhappy protagonist is rendered as both perpetrator and victim.

"Families come to the fore in this piece", says Anderson. "The family unit is the basic building block in so many societies - that's what's so fascinating about it."

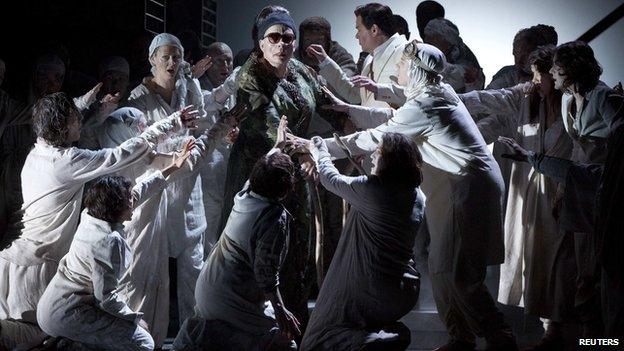

The production opens with the entire cast onstage. A plague is upon the people of Thebes. The sick and dying lie mingled and helpless, clothed in shroud-like robes. Their first utterance is a breath, a collective sigh, before they ask their King, Oedipus - the father of their city - to save them from the curse that afflicts them.

"The first act sees the downfall of Oedipus" says Anderson. "It shows his love for his wife, Jocasta, and her love for him, which is ultimately destructive".

.jpg)

Anderson translated Sophocles while studying Greek A-level

Fast forward to act three, and we see the death of Oedipus, in what the composer describes as "a kind of pre-Christian transfiguration".

The action is set in a sacred wood outside Athens. Trees stripped to trunk and branch recall images of First World War battlefields. The air is heavy with incense that drifts from votive bowls.

"This is a mysterious place where anything can happen," says Anderson.

"We're not even sure if the characters are alive or dead here. The music hovers and floats in this scene, reflecting the otherworldliness of the wood.

"But what becomes clear is that Oedipus is a terrible father. He encounters one of his sons, and beats him to the ground, cursing him."

Later in the scene, "Oedipus hears God's voice calling him to death," the composer explains.

"He walks off stage in a blaze of blinding light. But he doesn't allow his daughter, Antigone, to see him die. So she is denied closure on her father's death."

Matthew Best (r) plays Tiresias

It's an episode that Anderson can relate to closely. He was abroad when his own father died, and he was unable to see the place where it happened - a hospital bed - since it was occupied by somebody else.

Anderson poured his feelings about his own father's death into the scene.

"I felt Antigone's mind," he says.

"We understand that Antigone has taken on too much of a burden from her father, Oedipus, and he has put too much on her.

"The serenity of the wood has been compromised by the intervention of these family relationships, and we see that the slightest disturbance can lead to violence."

During the intervals, Anderson is found in intense exchanges with conductor Edward Gardner, checking the fine detail.

There are six more performances of the opera - the final one is on 3 June

"It's scary to do a new opera on some levels," says Gardner. "You're having to create something without any performance tradition."

On the other hand, he says, those traditions can be a burden. With a new piece there is no need to fight against preconceptions about how any given opera should be performed.

"The other great thing is that you can have the composer and the librettist in the room," Gardner continues, saying he can ask them both questions and even get them to change things.

"You really feel you're creating something from absolutely nothing, to the final product."

The conductor feels his main task is to realise what Anderson had in his mind when he wrote the music. But he has still found room for artistic interpretation of the score.

'Mutual trust'

"I've realised there is scope for dramatic pacing and actually it's lovely to find those points - where you need to ramp it up for intensity, or where you need to find a moment of repose," says Gardner.

"You really feel how a piece should pace itself."

In contrast to the secrecy and suspicion driving the onstage drama to its catastrophic end, well-established working relations between composer and conductor help the production ease its way past any problems that might arise.

Gardener and Anderson have known each other for a long time.

"It must be awful (for a composer) to write something for five years and not know that you can trust the conductor to deliver. But we've known each other a long time so I think there is a mutual trust", Gardner says.

"He (Anderson) feels open to tell me exactly what he thinks is working and not working, and to be honest, I'm the same way."

"If I don't feel a singer is getting through a certain point, we change the balance of the orchestra," says Gardner.

"We took out a little bit of brass in the third act to let the offstage chorus come through," he explains. "Julian is so open, and he's got such dramatic nous that it's no problem at all."

And for Anderson, the opening night is the realisation of an idea that first planted itself during his school days.

"I translated Sophocles while studying Greek A-level. I was having a tough time of it - it's a difficult text - but one line lit up the story for me.

"I translated a line delivered by Oedipus during an argument when he says, 'You would provoke a stone to anger'", Anderson recalls.

"I thought it was such current language. Somebody could have said that to me this morning."

With staging that is deliberately timeless, the opera hopes to bring to 21st century audiences a fresh interpretation of a drama that has continued to fascinate for 2,500 years.

There are six more performances of the ENO production of Thebes - 8, 10, 17, 23 and 31 May and 3 June.

- Published12 July 2013

- Published29 April 2014

eno,tristramkenton.jpg)