Artist Ryan Gander: Painting is 'an illogical act'

- Published

Ryan Gander, one of Britain's most acclaimed contemporary artists, has opened his largest UK solo exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery.

This year, he is also exhibiting in London, Tokyo and Singapore. Above, he is pictured with his work Magnum Opus, which consists of a pair of animatronic eyes on the wall of the Manchester gallery. Instead of the visitors looking at the gallery, the gallery is looking at them.

"Spectators go into art galleries and make judgmental decisions," Gander explains. "I always thought that you could see it in their eyes, what they were thinking. So I thought it would be nice that the institution is given the ability to critique as well, with its eyes."

These clusters of colours are actually palettes that Gander used to paint portraits of people he has known. In an attempt to subvert conventional portraiture, the artist has destroyed the paintings themselves and put the palettes on show instead, leaving the viewer to imagine each person from the leftover blobs.

It is one example of Gander asking his audience to use their imaginations to fill in gaps. "I've always thought it was really strange that artists made paintings and threw away the palettes, because the palettes are like happenstance abstract wonders," he says.

"For me, the phenomenon of having the palette, which is the by-product, the left-over, the fallout of making a painting, is infinitely more wondrous than spreading oil on canvas to make a picture. It seems quite a futile, illogical, unintelligent act to me."

Many of Gander's works celebrate the wonders of the imagination, and he has created a mock government advertising campaign urging people to harness their imaginations.

"If you see problems in the world, a lot of people moan about them or criticise," says the artist. "I think it's better to work from example - just do it. You can change anything yourself. If you're intelligent enough and creative enough, you can infiltrate any system to make any change happen."

The adverts carry the logo of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills - but it is not a real government campaign. A mock TV commercial is being screened in the gallery, while posters and billboards are going up around the city.

Putting a new spin on the common art gallery gripe that "my child could do better than that", this sculpture - and others like it - are marble replicas of the dens that Gander has made with his five-year-old daughter. "The naivety of children gives them this beautiful ability to approach artworks without any cultural baggage that adults have with them," says Gander.

"Adults are genuinely scared, unless they've had visual training, of approaching contemporary art because they think they're going to get it wrong, or be made a fool of, or say the wrong thing. But it's very, very simple. There isn't a wrong thing to say. Any response is a worthwhile and valid response. Children don't worry about it."

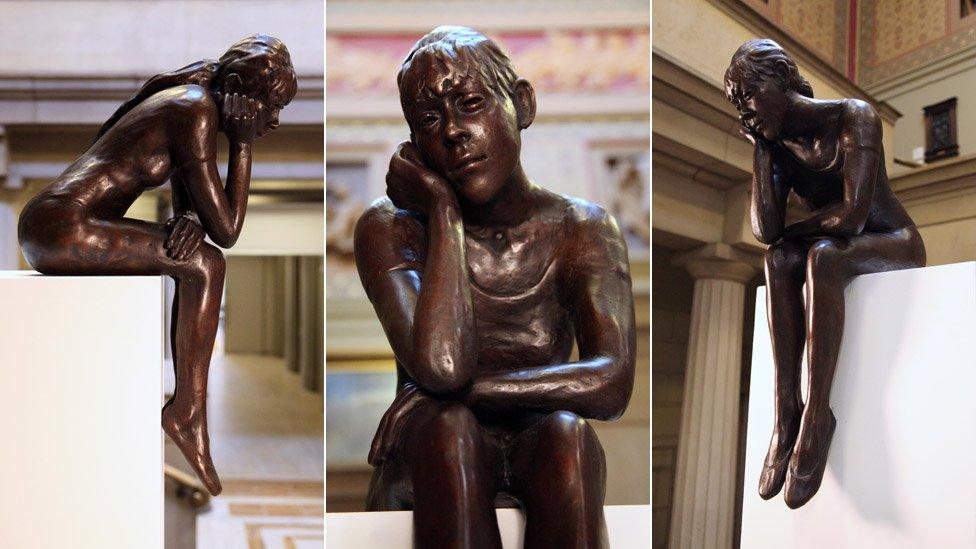

Gander has also freed Edgar Degas' elegant dancer from her formal ballet pose and put her in a new sculpture that looks down on visitors as they enter the Manchester gallery - another example of the art watching the onlookers.

"She was once an artwork, and then she came to life and she's looking at you," he says. "She's had the gaze for decades and decades, and now her gaze is returned upon the spectator."

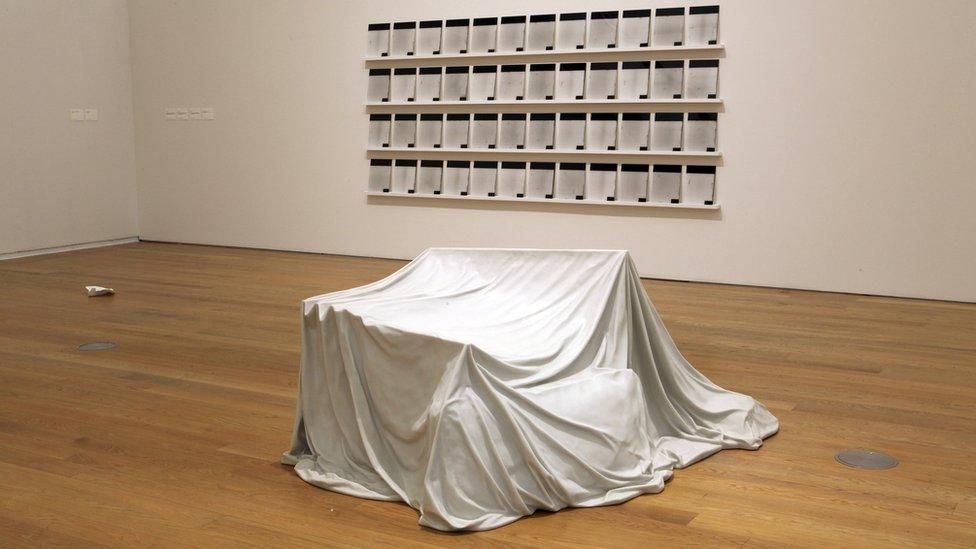

Peanuts illustrator Charles M Schulz has inspired a number of Gander's works. For the Manchester exhibition, he has framed 150 blank cartoon strips that Schulz used to draw Snoopy and Charlie Brown. The cards were left over when Schulz died in 2000.

"It makes me want to cry, this work," Gander says. "It's camouflaged as hardcore conceptual art, but it's actually heartbreaking romanticism." The work, he says, is all about what could have been if Schulz had not died. In an alternative reality, he would have lived and these strips would have been full. "So it's a life beyond him," Gander adds.

Gander is also creating a £340,000 public sculpture that will be placed in Beswick, east Manchester, in September. An artist's impression is shown above. The sculpture, titled Dad's Halo Effect, comprises three 3m (10ft) stainless steel chess pieces that are based on parts of the steering mechanism of a Bedford truck. Gander's father made such trucks while working for Vauxhall Motors in Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, in the 1980s.

Ryan Gander's exhibition, titled Make Every Show Like It's Your Last, is at Manchester Art Gallery until 14 September.