Turner at Tate

- Published

JMW Turner's Ancient Rome; Agrippina Landing with the Ashes of Germanicus, exhibited in 1839

Rivals in life, two of Britain's greatest painters Turner and Constable, are the subjects of major exhibitions in London.

The general consensus was that Turner had lost his marbles. Old age had addled his brain, leaving him incapacitated as a painter: a past master who was now only capable of splashing paint on a canvas in the most indiscriminate fashion.

That was the view in 1840, but not today. In 2014, the late works of Joseph Mallord William Turner are considered to be among his very best. The expressive brushwork, colour harmonies, dazzling light affects, and almost complete lack of pictorial detail is now seen as not only a pre-cursor to French Impressionism, but also to American Abstract Expressionism.

Turner is presented not as an old master, but a modern one: a radical innovator, who cared little for rules, and not a jot for the establishment. To re-enforce the point the notoriously avant-garde annual Turner Prize is named after the cockney colourist.

The truth is more subtle. Turner was a Romantic painter, who cared as much for words as he did for images. Many of his works are accompanied by texts or poems, either written by himself or those he admired. He was in many ways conservative, and nostalgic.

Turner's War: The Exile and the Rock Limpet, exhibited in 1842

He didn't want to rebel against the establishment, or art history - he wanted to be part of both. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, the most straight-laced of art institutions, of which he was a member. He much admired the work of the great landscape painters such as Claude, and often chose traditional mythical subjects for his landscapes.

His modernity was a compulsion to re-present the landscape for a new generation. It was an ambition shared with his great rival and contemporary John Constable, who arguably was the more radical of the two - painting en plein air with an uncompromising dedication to depicting reality.

Turner took a different route. While Constable concentrated on detail, Turner spent his life removing it. He wanted to arouse the viewer's feelings: Constable was factual, Turner sensual. And never more so than in his late paintings, made largely after Constable's death. There is a freeness and bravura to them: a pure, heady emotion. Turner doesn't just show a storm at sea, he puts you in the middle of it. You can't see much, the swirling mist of sea and fog make it difficult to distinguish between the objects and the elements, the waves are mighty, the chances of survival slim.

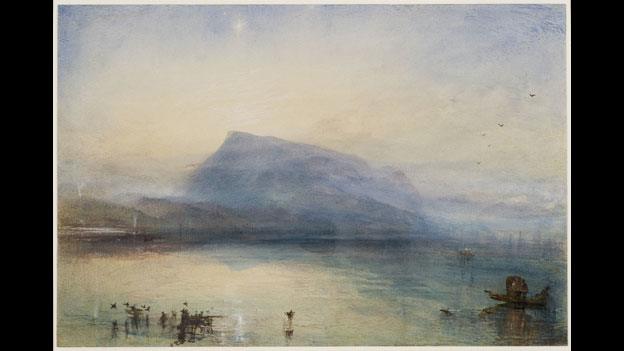

Turner's The Blue Rigi, dated from 1841-2

These late works feel cinematic: epic dramas writ large: think Spielberg meets Rubens with a soundtrack by Beethoven collaborating with Led Zeppelin. The colours are stunning, the compositions complex and often asymmetrical, departing in various directions. The few works in the exhibition that have remained unglazed give a truer indication of the artist's palette. The blues are paler, the yellows more muted. The honey-rich golden texture of many of his canvases look good, until you see how much better they would be without the sepia tinting of discoloured varnish.

Turner started out painting watercolours as if they were oils, and ended his life painting oils as if they were watercolours. That in itself tells of a restless artist who never stopped looking, working, thinking and experimenting. And that's what you get from his late works - an energy and freshness combined with ideas and opinions, evident in every inch of every canvas.

It has become the norm for painters to make large, increasingly abstract works in the final years. Monet did it, so did Rothko. Hockney is at it today. But, as with so much else in the world of modern art, J M W Turner was there first.