The changing face of Sherlock Holmes

- Published

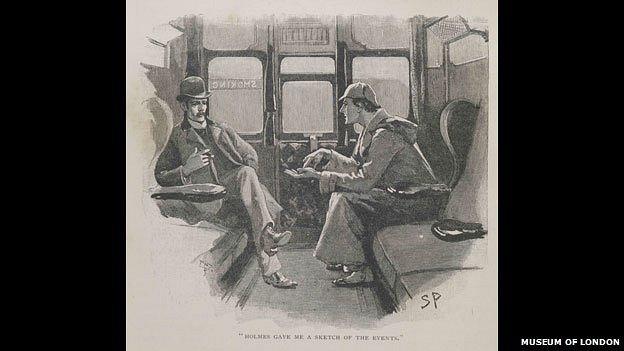

The early work of artist Sidney Paget is featured in the new exhibition

More than 125 years after his first appearance, the master detective Sherlock Holmes is as famous now as he was in late Victorian Britain. A new exhibition at the Museum of London recalls how he escaped the pages of fiction to be regarded almost as a figure from real life - and it investigates his relationship with the city that provided the backdrop to many of his most famous adventures.

Halfway through the Museum of London's exhibition Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived and Will Never Die, a large portrait hangs on the wall. It has seldom been seen in public before.

The oil painting dates from 1897 and is impressive in the Victorian manner. Though the man portrayed is not yet 40 he looks older: a person of substance, possibly a banker or politician.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was 27 when the first Sherlock story was published

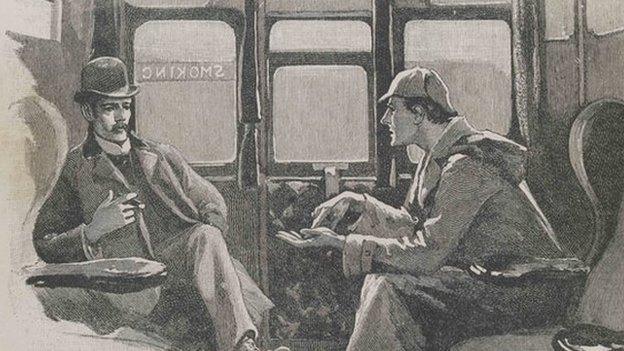

In fact the sitter was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who, a decade before, had created the world's most famous detective. By 1897 the fame of Sherlock Holmes had long outstripped that of his creator. Ironically that had a lot to do with the artist responsible for the portrait - Sidney Paget. Paget had also supplied well over 300 drawings to accompany the Holmes stories in print. Even today, they dictate our image of what Holmes should look like as much as what Conan Doyle himself wrote.

The new exhibition records the process by which the occupant of 221B Baker Street became a modern-day myth, at times straying far from what Conan Doyle wrote in 56 short stories and four novels. The impact of the many stage, TV and film versions is also investigated -- including the BBC's Sherlock, starring Benedict Cumberbatch.

Curator Alex Werner points out the Belstaff coat which they've borrowed from the makers of Sherlock. "Benedict Cumberbatch has worn it throughout and for a new generation it's as iconic as the original deerstalker and the pipe. But the pipe really comes from early stage portrayals by the American actor William Gillette... and it was Sidney Paget who introduced the famous deerstalker. Quite early on, Conan Doyle was already losing control of his creation."

The deerstalker hat first appeared in the story The Adventure of Silver Blaze

This is the biggest Holmes exhibition for decades. "We tried to balance Holmes artefacts," says Werner, "such as the first notes in which Conan Doyle mentions a character called 'Sherrinford Holmes' - with a broader cultural take on the Holmes phenomenon."

Unsurprisingly, the Museum of London show looks in detail at the part London plays in the stories. "London was changing in the 1880s and 1890s. Parts of it had barely changed since Georgian times but some bits Conan Doyle depicts seem quite modern to us now.

"But again you come back to what's in the writing and what grew up later. For instance we tend to think of Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson stumbling around in a thick pall of London fog. In fact fog is mentioned on only a handful of occasions. Maybe our collective imagination is recycling images from all those films, with hansom cabs rattling over the cobbles in black and white.

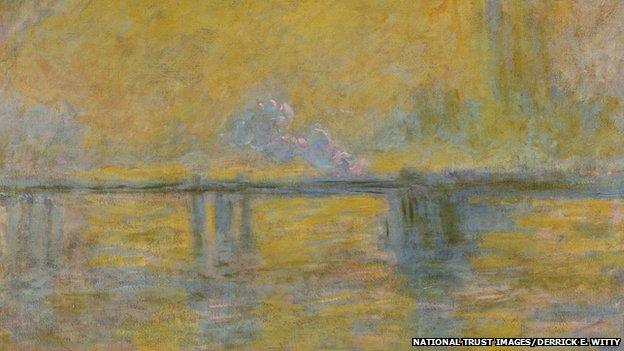

"But we do include one Monet image of London. The painting has no specific link to Sherlock Holmes but it shows the kind of sickly yellow fog which was characteristic of London in Conan Doyle's day."

The work of Claude Monet represents the fog of Victorian London

An enjoyable aspect of the show is the clips on view showing some of the actors who've played Holmes on screen over the years. Portrayals include those of Basil Rathbone in Hollywood in the 1940s, the BBC 1960s dramatisations featuring Douglas Wilmer (still alive at 94) and Jeremy Brett who played Holmes on ITV in the 1980s.

There is even a brief clip from a French silent film of 1912 in which Holmes is played by Georges Treville. A characteristic Holmes dressing gown is already in evidence.

In many ways, Holmes has seemed as real to later generations as actual Victorians such as Dr Livingstone or perhaps even Queen Victoria herself.

"Ever since he first appeared there's been a more or less non-stop drip of reinventions," says Alex Werner. "The BBC's Sherlock is the best recent example. No other fictional character can rival that."

Benedict Cumberbatch in the latest portrayal of the famous detective

Werner says that when Holmes appeared, mass publication was taking off, aimed at an increasingly literate public. "So Holmes and Watson lodged very clearly in the public mind very quickly. The strength of the British Empire took that image around the world - and then later the stories were perfectly timed to become useful to pioneer film-makers.

"Technological and scientific change helped a lot in establishing the myth. That's appropriate because science is a big part of the stories: it chimed with readers whose lives were being changed by innovations such as the telephone and the electric telegraph. By chance or otherwise, Conan Doyle's timing was perfect.

"Sherlock Holmes always was a modern detective and he's easily adapted to later periods. So if you see Holmes transposed to World War Two, as played by Basil Rathbone, it somehow works in its own terms.

"And as the Steven Moffat version has shown, you can play around with almost anything - as long as you keep the Holmes character and his relationship with Dr Watson."

Sherlock Holmes: The Man Who Never Lived And Will Never Die runs until 12 April 2015.

- Published20 May 2014

- Published25 June 2013