Money for nothing? Paying for Performance Art

- Published

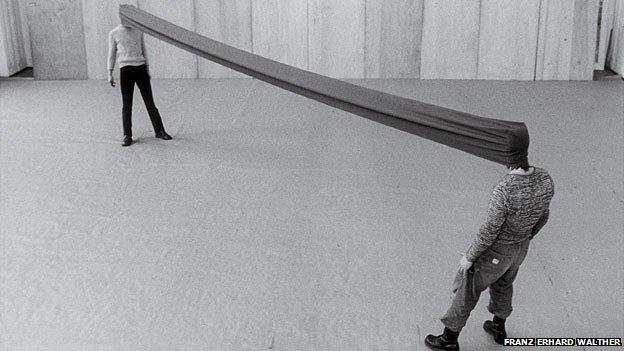

For £40,000 you can buy Franz Erhard Walther's stretchy fabric and perform your own Winkel

It was at the beginning of this millennium that an ambitious, dark-haired young dancer called Adam Linder enrolled at the Royal Ballet School. Here - in suburban Richmond, South West London - this thoughtful, curious student cavorted and sweated a great deal.

His hard work paid off. Two years later- in 2002 - he graduated from the Downton Abbey-like White Lodge to become a member of the Royal Ballet, where once again he cavorted and sweated a great deal.

But after three years at Covent Garden, Linder decided to swap the rarefied glamour of classical ballet for the darker edgelands of avant-garde contemporary dance. He went to work for the Michael Clark Company.

If you don't know Michael Clark's work, it is fair to say he is to dance what Stanley Kubrick was to film, and Malcolm McLaren was to music. He is a visionary, a provocateur: an iconoclast. His shows of the 1980s and early 90s have become the stuff of legend: spectacular theatrical rave-like events in which dance dallied with indie-rock, couture fashion and hip-hop.

Alexander McQueen, The Fall and Leigh Bowery were all part of the Michael Clark scene, with Bowery being a regular performer - he once came on stage wearing 10in high heels while carving the air with a chainsaw. Not the sort of thing that goes down well at the Opera House.

It went down well with the art world, though. It still loves Michel Clark; treats him as one of its own. Which he is in many respects, but not when it comes to his product. You can't own one of his works like you can a painting by Peter Doig or a Koons sculpture. Dance is a performance, not an object.

Sehkanal (1.Werksatz No. 46) in full flow

At least, that's been the case for the last few millennia, but not any more. In today's rampant and avaricious art market, one that is constantly on the lookout for new product lines to sell, ephemeral can be commodifed. Proof of which can be found in the 2014 form of Adam Linder.

You can go can go and watch him dance today or over this weekend. But not in a theatre or a concert hall or a dance studio, but in stand L5 at the Frieze Art Fair in London's Regent's Park. In this tiny white-walled booth on which scraps of paper containing handwritten texts have been stuck, you can watch Adam Linder going through his paces.

He is not presenting himself as a dancer per-se, but as a performance artist. He has given the work he has created and is performing a suitably arty title: Choreographic Service No. 2: Some Proximity. It is an improvised piece in which he and another performer / dancer respond to the writings of an art writer (whatever that is) "in real-time on variations of proximity between their two positions".

Adam Linder swapped the Royal Opera House for a cubicle

It sounds pretentious but is actually quite entertaining to watch. Anyway, that's not the point. The point is Adam Linder has turned his performance into a commodity, rentable by the hour. For £500 plus reasonable travel expenses, Choreographic Service No. 2: Some Proximity will be re-enacted by him and his chums wherever you wish. I assume that includes all the usual gigs: weddings, bar mitzvahs, hen nights and so on.

The work is part of a new 'Live' strand at the Frieze Art Fair, which its enterprising co-founders - Amanda Sharp and Matthew Slotover - have introduced to bring "some of the energy" of the burgeoning Performance Art scene to their fair. To encourage artists and galleries to take part, they provided six booths for free (hence their modest size, I guess) and invited all comers. Around 100 galleries applied, among which was Silberkuppe, Adam Linder's Berlin-based dealers.

Silberkuppe aren't the only Germans taking part in the Live activities. The Fulda-born artist Franz Erhard Walther was not personally present, but two of his 'action-based' sculptures are being presented by the Parisian art dealer Galerie Jocelyn Wolff (who had broken out of its tiny free space and commondered - with the blessing of Sharp and Slotover - a large area in front of it).

One of the works - called Sehkanal (1.Werksatz No. 46) I think - consisted of a plainly dressed man and a plainly dressed woman standing about twenty feet apart looking straight ahead. It was quite dull, to be honest. But was then enlivened when a second work - Winkel - was added, which involved them placing a stretchy piece of fabric over their heads (like a giant beany hat) and pulling back on it using their neck muscles to create something akin to the white strip at the top of a tennis net. This too, was for sale, in an edition of five at £39,400 a-pop.

For this you would get the piece of stretchy fabric and a certificate authorising you to re-enact the performance. This paper-based form of commodifying performance art has been going on for a while. Tate acquired a performance piece by the artist Roman Ondak (Good Feelings in Good Times) that consists of nothing more than a piece of paper with a list of instructions on how a few people should queue at an unopened door.

Hats off to the galleries who persuade punters to part with thousands of pounds for a piece of paper. Good selling skills and all that. But I'm not convinced that what is being bought is art. The American artist Sol Le Witt started this paper thing off back in the 1960s, saying the concept was the work of art, not its execution. Maybe. But then an idea isn't anything until it is realised, and once it has been realised, that's it. Any documentation containing instructions for its re-making is either a licence to make copies, or a piece of art history, or memorabilia - it is not the original, singular, unique work of art.

What's more, several of the artists who are involved in the instructions-selling business want to have a say in exactly how, where and by whom (performers) the re-enactment of their original work takes place. That's fine when they are still alive, but what happens to your expensively purchased piece of paper when they are no longer around? Surely Performance Art is all about the moment: you were either there or you weren't, and no amount of money is going to change that... yet.