Julien Temple on The Clash: 'The energy of punk is really needed now'

- Published

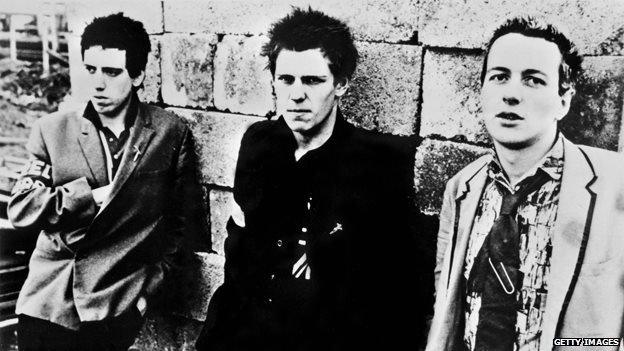

The Clash were relative unknowns when Temple filmed them in 1976. L-R: Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Joe Strummer

Director Julien Temple specialises in films on pop and rock music, most notably his dual Sex Pistols documentaries, The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle and The Filth and the Fury.

He's also one of the prime innovators in music videos, working with artists as diverse as The Rolling Stones, Duran Duran, Eric B & Rakim, Janet Jackson and David Bowie.

But in 1977, his student film about a promising new Punk band remained unfinished.

Now he's taken material shot with The Clash just before they became famous to create a documentary recalling the times which formed them.

As it airs on BBC Four, he says he's been surprised at the similarities between the beginnings of punk and today's Britain.

What were you filming with the Clash in 1976 and 1977?

I was at the National Film School and I was already filming with the Sex Pistols. The Clash weren't known at all outside a very small circle, but I thought they were an incredible band in the making.

So Joe Strummer, Mick Jones and Paul Simonon agreed to talk to me and let me film rehearsals in Chalk Farm in London, where it was freezing. Eventually, I filmed a gig at the Roxy club in Covent Garden, which disappeared long ago. The gig was on New Year's Day 1977.

With hindsight, the Roxy has taken on the aura of being vital to the early days of Punk, which may be an exaggeration. It had been a cheesy gay disco called Shaggarama's and in fact the Punk crowd soon lost interest in it and moved on. The Roxy got worse and worse and lasted about 100 days.

I filmed other gigs too, such as at the Roxy cinema - a terrible old fleapit in Harlesden which happened to share the same name. We also recorded, totally without permission, one Sunday evening at the National Film School studios at Beaconsfield. But it's the Roxy club gig which is the centre of the film.

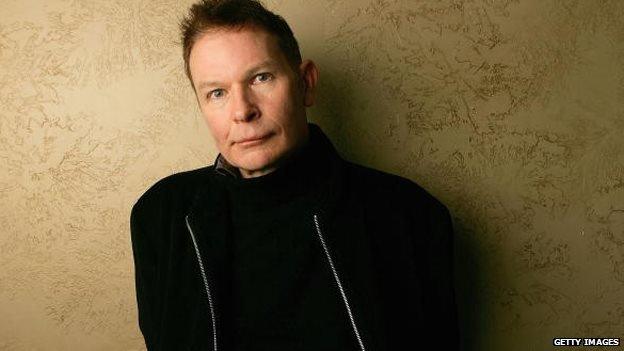

Temple made his name with the Sex Pistols "mockumentary" The Filth and the Fury

Where has the footage been for the last four decades?

Rotting away in my shed! I can't really explain why it's taken so long to do anything with it. I think this must be the last Punk artefact left.

Were you shooting on film?

The material was on a clunky half-inch video format which probably nobody now would believe if they saw it. You had to carry a big reel-to-reel recorder around and this box-like camera. And you had to wind on tapes by hand. It was right at the start of the video era and there's a sequence in the film where you see the band can't quite believe they're watching themselves back on TV because it's such new technology.

Why is the material in black and white?

The technology was incredibly basic: I was just working with my student grant. We affectionately called the format "Glorious Bogroll Vision" but really it was murksville. Today monochrome footage would be perfectly graded with high-contrast effects. But the 1970s format has a dropout-ridden, glitchy feel which I enjoy now. In fact, we cut in a couple of extra glitches we liked them so much.

"Glorious bogroll vision" - not an early precursor to Ultra HD

There's lots of material of the band-members talking, most of which seems enjoyably relaxed.

In fact at first they weren't keen on that - I think they thought being filmed wasn't a cool thing to do and they didn't want to explain their songs. They got bored. But it's interesting to see how Joe, Mick and Paul interacted. In one sense it was sad working with all the material of Joe Strummer [who died in 2002] because Joe became a great and lasting friend. But it's fascinating hearing him speak: Behind the street act you see there's a philosopher and a hugely thoughtful guy. When he speaks he has an unexpected turn of phrase which later informed his songs. There was none of the usual rock star excess and remoteness or paranoia with him.

What do you remember most about filming the Roxy gig?

That the PA system was on the blink. So the sound wasn't great but in film-making you grab chances as you can and the delays gave me time to do cutaway shots of the audience. The Clash were struggling with the sound but probably they played about 10 numbers and we use most of that in the film.

In fact, originally I wanted to call the new film On the Blink but not just because of the sound system. It's what Britain felt like in 1977.

And you use TV news archive to establish the wider picture.

A lot of the material we acquired from the BBC and ITN seems like it's from another world. Some of it is so twee and old-fashioned it feels like it's the 1950s rather than the 1970s. But it was important to have that stuff alongside the gig and the interviews: Clash fans are going to love the film but I wanted to grab other people too.

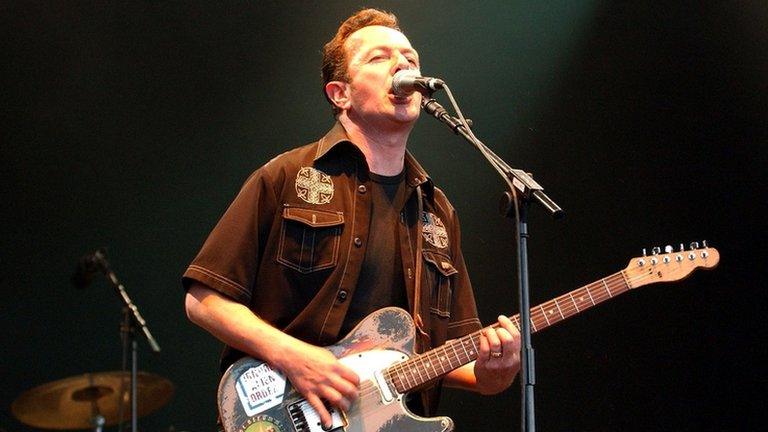

Temple's glitchy, raw footage captures the band at work and play

So is this an exercise in nostalgia?

Quite the opposite: I think it's about the future, not the past. Punk is in some ways a challenge still to be met. I think the energy of Punk is really needed now, though it'll have to raise its head in other ways.

I don't think it can come now in rock and roll form - society has changed and young people experience so much online. I think, like most change, that's partly good and partly bad. The negative is that kids seem almost to have forgotten how to get together and do something of their own but they're still working with others.

There are new bands making great music but things are compartmentalised into niches because of the internet. From about 1976 the whole of Britain - and not just Britain - knew about Punk, whether they loved it or were appalled. It wasn't something for the cognoscenti.

There hasn't been a phenomenon like it since and looking back at this material I realised I was lucky to capture one of the key bands as it got going. It was three months before the Clash's first album. The basis of any real band is the personalities more than technical talent: The Clash had personalities which were conflicted and sympathetic at the same time.

The band were in their mid-20s when you filmed. What will people of that age now get out of the film?

Punk was about originality and young people not parroting what was fed to them. So it would be ironic if people saw this and just wanted to copy Joe and Mick and Paul. But I see this as a challenge for kids: I want them to see it isn't impossible to get up and say something original to you.

The film makes it clear you see parallels between Britain then and now.

The fear of cuts and the fragility of the financial system isn't that different. There are fears of immigration. Some people feel marginalised in the same way. So maybe there will be a huge outburst of energy, the way Punk was. But I think an unexpected explosion is likely to come through the internet, not through rock and roll chords on a guitar. We've done that.

The Clash: New Year's Day 1977 will be screened on BBC Four on 1 January, 2015.

- Published22 December 2012

- Published19 July 2013