Art and science collide to reopen Whitworth gallery

- Published

In the lab with Cornelia Parker and Professor Konstantin Novoselov

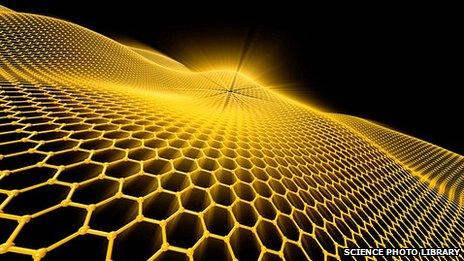

One of Britain's leading artists has teamed up with a Nobel Prize-winning physicist to turn fragments of drawings by William Blake, JMW Turner and Pablo Picasso into the so-called "wonder material" graphene.

The fruits of Cornelia Parker and Professor Konstantin Novoselov's experiments in art and science will reopen the Whitworth art gallery in Manchester on Friday after a £15m expansion.

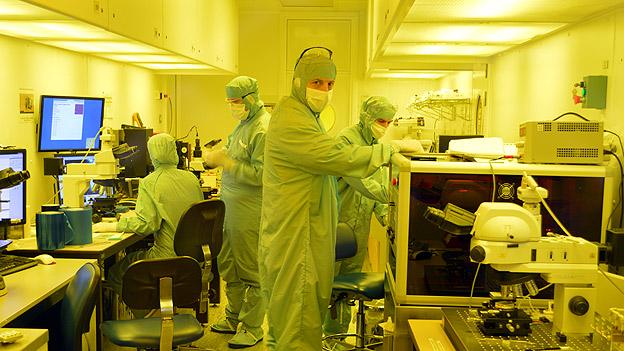

The laboratory where graphene was discovered looks just like you hope a top scientist's lab will look.

In the corner, a large steel vat with the word "cryogenics" on the side has frothing gases flowing from its spout, looking like it may have been bought second-hand when Top of the Pops was taken off air.

There are banks of electronic modules with flashing red digital displays and wires winding from one to the next.

Down the road, people are dressed head-to-toe in protective clothing and bathed in artificial yellow light as they peer through goggles into microscopes.

It is tempting to assume that Professor Konstantin Novoselov will complete the picture by entering in a lab coat and with zany white hair.

But the Russian-born boffin, personable but unassuming in jeans and a grey jumper, is no mad scientist. He is one of the two brilliant graphene pioneers who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2010.

The graphene was obtained by slicing layers of graphite from pencil drawings

The Whitworth art gallery in Manchester is ready to reopen after a £15m pound revamp.

Their discovery was a very thin form of carbon, a single atom thick, which is apparently 100 times stronger than steel and conducts electricity better than copper. It will supposedly revolutionise our lives.

Prof Novoselov - known as Kostya - is also an art lover. So when he was asked to work with Cornelia Parker, one of Britain's most acclaimed artists, he says he "jumped on it immediately".

It was in these University of Manchester labs that the pair came up with the idea of taking tiny fragments of graphite from the pencil lead on drawings by Blake, Turner, Picasso and Constable and turning them into graphene.

"She had this vision that we can bring back to life the old drawings of the old masters," Prof Novoselov says.

"Of course that possibility's only once in a lifetime, to get my hands on the old masters, and probably correct a few things which they did wrong.

"I picked a few specks of graphite from there and turned it into graphene."

Graphene was obtained from William Blake's Study for Tiriel Denouncing his Sons and Daughters (1789)

Prof Novoselov has a glint in his eye when he suggests that he has removed a few pencil strokes to "correct" these great artists' mistakes.

The amount of graphite he actually removed was minute. "You would never know that there has been anything taken from those drawings," he adds in case anyone did not get his little joke.

"I work with pieces of graphite that are sub-100 microns (0.1mm), so you would never notice those with the naked eye."

The drawings he took graphite from include William Blake's Study for Tiriel Denouncing his Sons and Daughters (1789).

The graphene he extracted from that picture has now been used to make a sensor that will trigger a firework display at the nearby Whitworth gallery on Friday.

The firework display has been designed by Parker, who has added bits of meteorite from Arizona to the fireworks to make a sort of meteor shower.

"I'm re-enacting the meteor's fall in a firework display," says Parker.

Prof Novoselov and Parker have worked on the project in his office at the University of Manchester

The sensor make from the William Blake graphene has been kept in a sterile laboratory

Parker was inspired by Blake's poem America: A Prophecy, in which he wrote of "flam'd red meteors" and "terrible wandering comets".

"He's very biblical in his proselytations about the firmament, and so somehow this firework display is going to be a Blakeian firework display," she explains.

Like the lab, the Whitworth is owned by the University of Manchester. As well as arranging the fireworks, Parker is exhibiting at the Whitworth as part of its reopening line-up.

The gallery has been shut for redevelopment since September 2013 and will reopen to the public on Saturday, having doubled in size and gained a new wing and an "art garden" in the neighbouring Whitworth Park.

A new wing has been built onto the Whitworth's original Victorian building

Parker is a former Turner Prize nominee and was the only living artist in the top 10 after a survey to find the most popular British artworks in 2013.

Long before dabbling in graphene, she made her name by examining, dismantling and playing around with familiar objects before allowing us to look at them anew.

She crushed silver with a steamroller, enlisted the British Army to blow up a garden shed, made a magnified image of a hole in a pin cushion made by Charlotte Bronte and microscopic portraits of the chalk crystals in Einstein's equations.

The Einstein work was made while she was artist in residence at the Science Museum. There is now talk of her doing a residency at Cern, the home of the Large Hadron Collider, in Switzerland.

'Genius' ideas

"Artists and scientists are very close," Parker says. "They always have been, but I think we've just been divided out over the last few centuries into specialisms.

"Leonardo da Vinci was drawing helicopters and all kinds of things. We're artificially divided. I think we're closer than we think we are."

Artists and scientists both rely on curiosity, willingness to learn and imagination, Prof Novoselov believes.

"Artists and scientists both think outside the box," he continues. "They've got to come with genius experiments or ideas to expose the most interesting phenomena.

"Later, they've got to diverge a little bit because scientists will start to look at the common elements between many of the phenomena to describe the most general law, and artists will probably try to study individuals rather than the crowd as a whole.

"But we're just two sides of the same medal."

- Published7 March 2014

- Published10 September 2014

- Published15 January 2013

- Published5 October 2010