How do you make a drama about dementia?

- Published

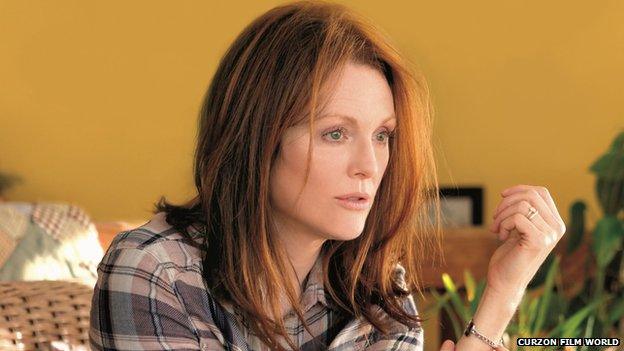

Still Alice tells the story of a 50-year old linguistics professor who is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's

Still Alice, released in UK cinemas today, is the latest in a wave of productions about dementia. How do dramatists try to convey what it's like to experience the decline of the brain, both from a personal perspective and through the effects it has on others?

Julianne Moore has already won an Oscar and a Bafta for playing the title role in Still Alice - a 50-year-old linguistics professor who is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer's.

Other dramas to have depicted the challenging subject of dementia in recent months include the UK stage plays Visitors, external, An Evening with Dementia, external and The Father, external; while How Did I Get Here? a comedy drama tackling the topic, was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 last month.

"I think [dealing with a parent who has dementia has] become one of those things which is a life stage," says Jonathan Myerson, explaining what drove him to write How Did I Get Here?

His late mother developed symptoms of vascular dementia in the last years of her life, "so I had personal memories of that", he says.

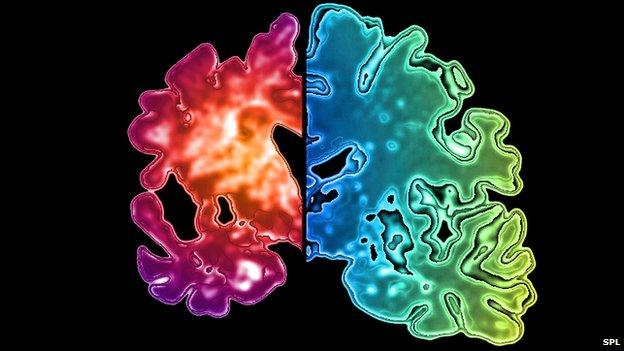

The subject is especially poignant at a time when 850,000 people in the UK have a type of dementia (the term is used to describe a set of symptoms that occur when the brain is damaged by certain diseases). The Alzheimer's Society predicts that figure will rise to more than 1 million by 2025.

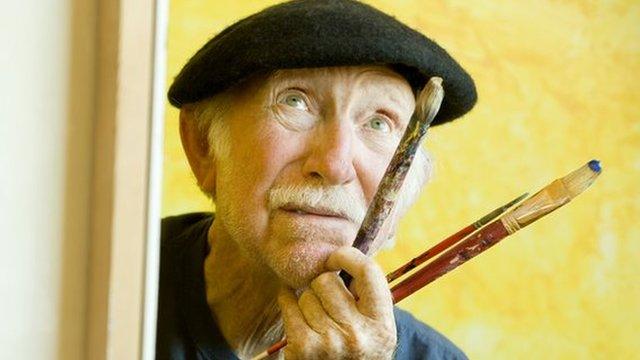

Four actors convey one woman's experience of dementia in Autobiographer by Melanie Wilson (right)

But rather than focusing on the "tragedy" of the condition, Myerson was keen to write "something that was affectionate".

In his radio comedy, Granddad, who has dementia, and daughter Rebecca are visited by Dad; a version of Granddad as his younger self. But Dad is an agent of mischief: He dishes out bad advice and is not always welcome.

Myerson was interested in the dramatic potential of the question: "What would it be like if you could suddenly talk to your parent again?" But it was also important to him to show "the ongoing state" of a family in which someone has dementia, "because it tends to last for several years, if not more".

Writer and performer Melanie Wilson used four different actors to play a woman in the middle stages of dementia in her 2011 stage play Autobiographer, external. The audience embarks on 76-year-old Flora's journey as she collides with herself at different ages through fragmented memories.

"[Flora] is engaged in a constant attempt to remember; to keep hold of her own story and identity and relate that to the audience [and] to herself," says Wilson, who explains her work was influenced by memories of her grandfather, who she suspected had dementia before he died, although he was never formally diagnosed.

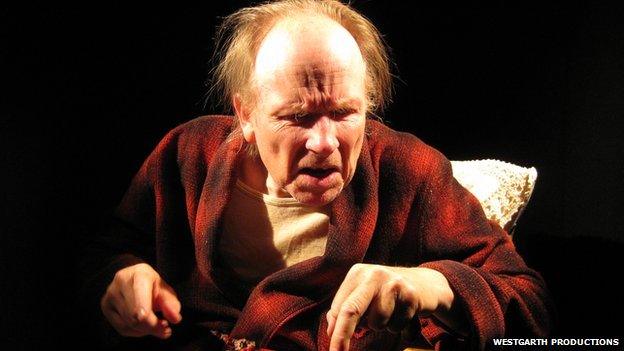

Trevor T. Smith performs An Evening with Dementia for health care workers as well as theatre audiences

Taking on such an emotive topic inspires a strong sense of responsibility amongst dramatists.

For some, gathering hefty amounts of medical research is essential. But Trevor T. Smith chose a different approach for his widely praised one man show An Evening with Dementia.

"We can all imagine what it's like to have dementia," he says.

"I didn't do any [traditional research] at all… Everyone thinks these days they have to do research for everything. Our common sense is really negated."

For a play based on intuition, he was stunned to receive plaudits from medical bodies for his accurate portrayal.

Before the play begins, Smith sits on stage in character, an ex-actor who lives in a care home, "twitching and not knowing where he is". He begins to talk to the audience, slowly at first, then inviting them deeper and deeper into his world.

"The first few pages of the play are full of jokes. And then I put the boot in later," says Smith.

Towards the end the character reveals he never speaks to anyone in his care home, but loves talking to his audience inside his head.

Barney Norris's play Visitors portrays the marriage of an elderly couple while one of them - Edie - has dementia. One device Norris uses to convey Edie's personal battle is through monologues, which are ambiguous, leaving the audience guessing whether they're internal or spoken out loud.

"But they're sequences in which Edie tries to set certain memories in amber as others burn away, tries to keep hold of moments she wants to have defined who she was," explains the writer.

"I simply tried to truthfully and lovingly depict a woman's decline. Every case of dementia is different and unique."

Can films such as Still Alice increase the public's understanding of dementia?

Norris admits he was worried what people with real experience of the condition would think.

While touring hospices, he considered cutting certain lines for fear of "putting people into certain parts of their heads". But decided against it, "because of course cutting lines is just another kind of disrespect".

"And actually, those audiences loved the play."

Before Still Alice's release, the Alzheimer's Society sent copies of the film to people in its network. One person who reviewed it for the organisation was Rebecca Stevenson, whose father developed early-onset Alzheimer's when he was aged just 52.

"I was nervous to watch it because it's such a close topic to my heart," she says.

"It's been 14 years since dad was diagnosed. He was at home for 10 years, my mum cared for him, and then he's been in a home for coming up to five years now.

"And those 10 years we have some wonderful memories," she says. "We knew what was going to happen to dad so we created some amazing memories, but sometimes there were some very, very difficult moments."

Stevenson thinks dramas like Still Alice could help increase the public's understanding of early-onset Alzheimer's, which she says is often misunderstood.

"The disease is very much a disease behind closed doors."

Cathy Baldwin from the Alzheimer's Society believes as long it is "fair and balanced" drama can help change public perception "of the negativity often related to dementia".

She commends Still Alice's portrayal of the personal journey of dementia and "the sense of losing the essence of oneself."

"Our lives are all so very complex, we seldom think about the various elements that make us who we are, and that includes professional and personal; a wife; partner; mother; grandmother; sister; daughter.

"It is impossible to separate these out as they are all interlinked to create who we are."

- Published21 February 2015

- Published14 October 2014

- Published18 March 2013