Alexander McQueen: Revolutionary and friend

- Published

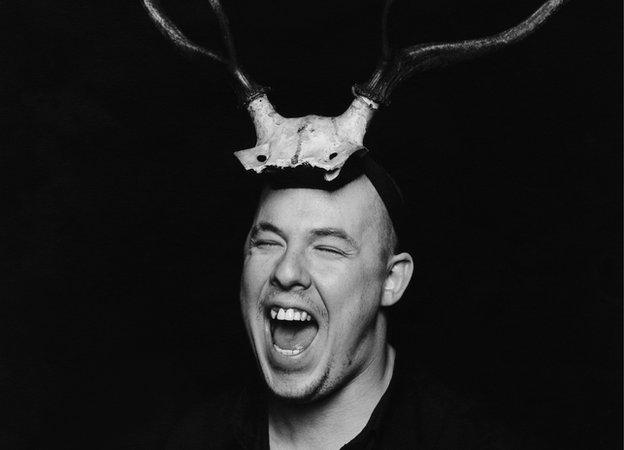

Alexander McQueen's friend John Maybury: "He had enormous creativity and was rich in ideas"

As Savage Beauty, the new V&A exhibition about Alexander McQueen, opens 20 years after the London show that got him noticed, two close friends and his biographer share their memories of the talented, revolutionary fashion designer.

Until his death at 40, McQueen remained a controversial talent projecting a highly marketable streetwise image. Former boyfriend Andrew Groves, who worked on the 1995 show, saw him hit the big time and observed the pressures.

For two years from 1994 Groves was in a relationship with McQueen. "Or as the fashion world would have it, for four seasons," he says.

Like most of the designer's friends, Groves, who now lectures on fashion in London, refers to McQueen by his first name, Lee.

"I was in a bar in Soho with a friend and he said: 'Look, Lee McQueen's there.' So I said: 'Let's go and meet him.' Probably I was a bit drunk, but if you're a fashion animal you want to know what everyone's up to.

"This was before Lee became really famous, but he'd already created a stir with his runway shows. He'd been written up as being outrageous, but in my eyes he was no more out there than lots of people you'd meet in a gay bar in the mid-'90s.

"The first thing that drew me to him was his sense of humour: he had the most dirty laugh! I think he was wearing jeans and a T-shirt and maybe an MA1 jacket. All the time I knew Lee, I don't think he wore anything worth more than £30, ever."

Innovation and creativity became Alexander McQueen's badge of honour

At the end of the evening, Groves headed back to where McQueen lived in east London.

"He told me he had to get back to Chadwell Heath and I thought I've never been there, sounds fun. So we got to Liverpool Street station where we jumped the barriers and then the train ride went on for ever in the dark. At the other end there was a huge long walk to somewhere near Dagenham.

"I was starting to regret the whole thing, but Lee was just about to start on his next collection and he realised that I could sew and pattern cut. So he decided it might be good to have me around.

"It was an interesting time in British fashion. London Fashion Week had almost no one decent showing in it. Someone like Lee could put on a show for virtually no money and people would come."

'Anarchic element'

Some fashion journalists disliked the Highland Rape collection in March 1995, thinking it trashy and sensationalist. McQueen later claimed the title referred to England's rape of Scotland, but by then the show had won him the publicity he had been seeking.

McQueen had grown up in Stratford in east London, long before its Olympics makeover. He left school at 16 with a single O-level in art.

Two things changed him. First came an apprenticeship in Savile Row, the London home of traditional men's tailoring. He found it dull, but realised he might have talent as a cutter. Then he spent time in Milan with designer Romeo Gigli.

From McQueen's mid-20s, his rise was extraordinary.

The film-maker John Maybury is known for biopics of Dylan Thomas and Francis Bacon. He can't remember exactly where he first met McQueen, "but it must have been a nightclub scenario or some other scenester hangout. It's what we all did," says Maybury, who went on to work with him on videos for catwalk shows.

Friend and former lover Groves was distressed by McQueen's suicide "but not wholly surprised"

"Lee was enormously funny and he had a real anarchic element. To succeed in fashion you need self-possession and real drive.

"For all the apparent frivolity it's a tough world and at the upper levels there are huge amounts of money involved: there are parallels to making a career in film. Lee coped with all that but you can't ignore the effect pressure has in the long term.

"He had enormous creativity and was rich in ideas. People have said Lee's energy had to do with escaping working-class origins, where creativity wasn't valued.

'Fanatical worker'

"But I've worked as a film-maker in fashion and it's an industry where no one's very bothered where you come from. What matters is coming up with the goods - meaning new collections. Innovation and creativity are complex and I thought Lee saw his class status as a badge of honour.

"Once Lee became designer in chief in Paris for Givenchy [in 1996] he might be doing four collections a year. That's asking an awful lot of any person, whatever the salary. And you can go out of fashion overnight."

Some thought McQueen's streetwise image sat oddly with a chic and established firm like Givenchy. But by the 1990s the economics of fashion were changing.

McQueen succeeded British designer John Galliano in Paris. Both men were usefully high-profile in an industry whose income depended now less on haute couture than on using well-known brands to market perfumes and accessories.

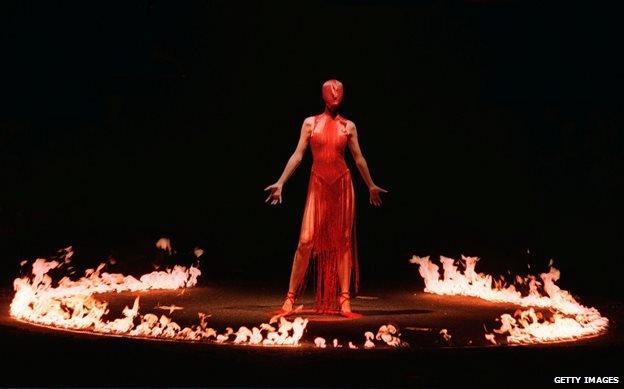

McQueen's shows were theatrical to the point of becoming "performance art", says his biographer

Maybury says when he worked on the videos for McQueen's Irere collection in 2003, it was clear the pressure on him was non-stop.

"He was a fanatical worker. There were drugs around, but from what I saw I think that's been overstated as part of Lee's life.

"He was always interested in the film-making process and in the visual generally: I think Lee McQueen's eye went beyond fashion in a narrow sense.

"Anyone who knew him will tell you he had an innate sense for shape and colour. If he'd lived, I think maybe he would have moved into different artistic areas."

McQueen's recent biographer, Andrew Wilson, became fascinated with him when he went to the show Voss in 2001.

'Powerful and dark'

"It was half-way to performance art: People call it the Asylum show. You had models like Kate Moss wrapped in bandages as if they were in some awful institution.

"At the end there's a box and the sides come down and there's an overweight naked woman with a gas mask and moths flying around her. It was an incredibly powerful and dark experience. McQueen didn't censor his imagination.

"But at the same time he was a master cutter: He tailored superbly and the silhouettes he created will be classic a hundred years from now."

McQueen killed himself at his London home in February 2010, a few days after the death of his beloved mother Joyce. Has Wilson come to a conclusion about why he took his own life?

"Of course there was grief at his mother's death. But I think there were other reasons too.

"He loved the fashion world but he also hated it. I think by the time he was 40 he wanted to leave fashion behind.

"But by then there were so many people around the world whose jobs depended on him and on his talent. He told a friend he'd made a gilded prison for himself.

Alexander McQueen's designs were as intense and unique as the man himself

"But in a couple of decades he'd achieved so much with his fearlessness. Coming from his background so many people would have thought I'm not even going to try - what's the point if you're not going to succeed? But he wanted to make the best of his life."

Groves' relationship with McQueen was long over by 2010. Yet he says news of the suicide was hugely distressing.

"But it wasn't wholly a surprise. This was someone who didn't want to be quite good: he wanted to be the best talent in fashion ever. Better than Dior, better than Chanel.

"If you're judging yourself by those standards, that's going to take a toll."

Biographer Wilson sums up McQueen's character in a way many friends would echo.

"Perhaps he felt his life was going to be an intense one but a shortened one. He went through life with this great intensity, as if he was trying to squeeze everything out of every single moment."

Savage Beauty opens on 14 March and runs until 2 August at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.