British Museum defines Greek naked ideal

- Published

The Greeks were totally "at ease" with the nude male, says curator Dr Ian Jenkins

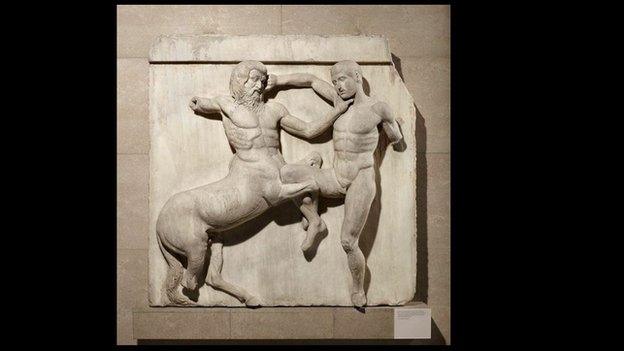

The art of Ancient Greece focused unashamedly on the naked body. Female nudity was treated discreetly but the unclothed male form was everywhere.

The show Defining Beauty at the British Museum investigates the Greek obsession with physical perfection - and the man in charge says there's an obvious parallel with people's desire today to look good at the gym.

Dr Ian Jenkins is the British Museum's expert on classical Greek sculpture. Yet even he finds it hard to explain exactly why the naked human form featured in the art of Ancient Greece in a way it didn't in other cultures of the same era.

"If you look at Assyrian culture or the Egyptians or the Cypriots they weren't at ease with the naked body - mainly the male body - in a way the Greeks were," he says.

"The same was true of Roman culture before it came under Greek influence. I don't think there's an easy explanation why.

"It may in part be the importance of culture in defining Ancient Greece at all. Apart from shared cultural values there was language and the recognition of the Olympian gods: those were the big unifying elements.

"So the focus on the body may have linked what was really a scattering of city states rather than a nation or an empire. Not all the artwork shows the body naked but a lot of it does. For the Greeks the body had almost entirely positive connotations: there was no shame."

Some of what's in the exhibition verges on the risque. But Dr Jenkins makes a distinction between naked and nude.

Representations of female nudity were treated with caution in comparison to those of the male form

"To me, naked is when your underpants elastic goes ping in Athens High Street and you're left compromised. But, at least for men, nudity was a club and heavily circumscribed by rules.

"For a man in Ancient Greece to be naked at, say, the wrestling academy was to join the ranks of the righteous. Representations of the naked male were common and I doubt they ever shocked anyone."

Defining Beauty brings together around 150 items, mainly sculpture. Some are beautiful originals from Ancient Greek times (roughly the two and a half millennia BC), but others are marble or bronze copies from Roman times or the modern era.

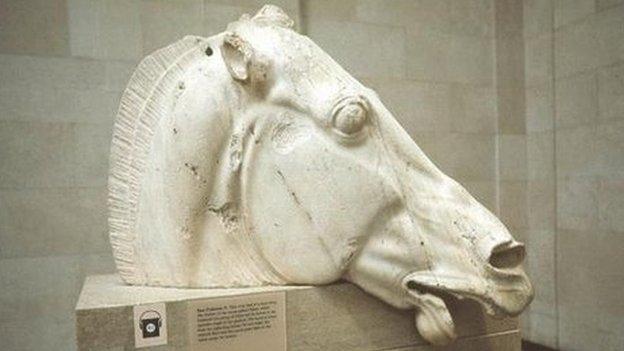

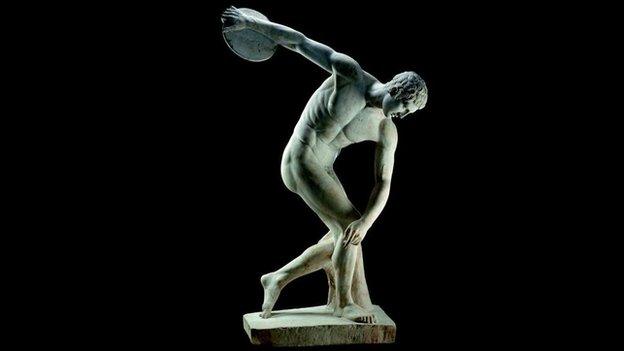

The British Museum has moved parts of the Elgin Marbles to the show, allowing them to be studied for a time in a different context. Some other pieces, such as the marble statue of a discus thrower, are also long-term inhabitants of the museum.

Others are on loan, such as the Vatican's incomplete but impressive Belvedere Torso of the First Century BC.

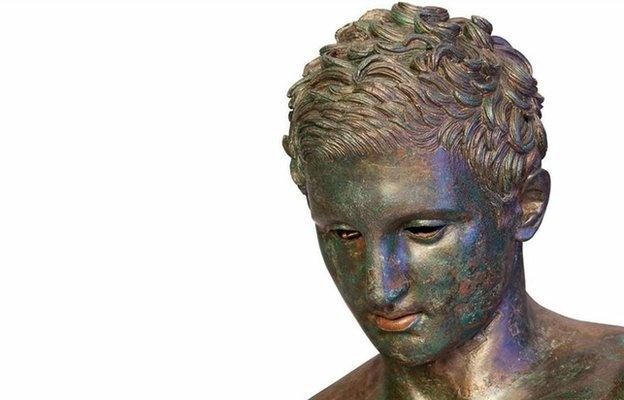

A bronze Apoxyomenos (an athlete scraping sweat off his naked body) is on loan from Croatia, where in 1996 it was discovered, apparently by accident, beneath the Adriatic.

Defining Beauty isn't only about the Alpha Male community of Ancient Greece, but it's the part of the exhibition which has the most obvious echo today.

Paul Standell is an actor and personal trainer who runs a website delivering to clients the kind of physique to which, 20 years ago, few in Britain aspired.

He says he's had clients hoping to attain a "Greek statue" look.

Curator Dr Ian Jenkins says modern gym culture has brought us closer to the mindset of Ancient Greek times in terms of admiration of the body

"Always it's the men. Possibly what they mean is they want to look like Brad Pitt in Troy or Dwayne Johnson in Hercules: I suspect a big movie influence on what people expect an Ancient Greek hero or god to look like. They want the arms and the chest and a Hollywood six-pack."

So how does Paul rate the 3,000-year-old skin-scraping athlete? Would he make a magazine cover in 2015?

"In many ways it looks like the male ideal hasn't really changed. He and the discus thrower show many of the physical characteristics they'd need to get work as a fitness model today.

"Proportions are vital. So if you take the waist as one, you want shoulder-size to be 1.4 and that's pretty much what you see in the exhibition. They've also got good obliques, defining the mid-line of the body.

"There's excellent calf definition too and the shoulders and chest are visually separated, as they need to be. It's exactly what some male clients want today.

"But it's interesting that recent tastes go beyond that. Though it pains me to say it, an agent handling fitness models in London or LA might tell these guys to go away and get even more defined, even more cut. Or maybe they just need a tan."

Having seen the exhibition, Standell thinks the Ancient Greeks had a more realistic view of anatomy than we do today.

The Elgin Marbles are put into a completely different context as part of the exhibition

"Of course they didn't have Photoshop to contend with," he says.

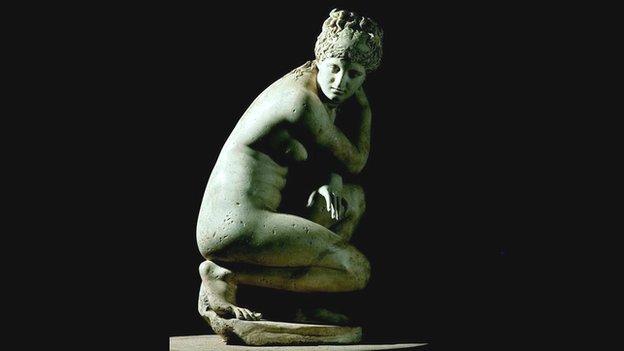

Dr Jenkins says the female figures are represented in the exhibition with a greater modesty - up to a point.

"The fact is that in Ancient Greece social convention meant a respectable woman would never be seen unclothed.

"So a representation of Aphrodite (goddess of love) might show her bathing as that's a situation in which a woman can legitimately have no clothes on. But even that came relatively late in the Ancient Greek period.

"Sculptors often resorted to drapes or sometimes to a modestly placed arm. Of course, you may argue that a finely executed tissue of drapery could make the image more erotic rather than less."

Dr Jenkins says modern gym culture has brought us closer to the mindset of Ancient Greek times in terms of admiration of the body.

"We have become franker about physique and that trend is developing even now. Look at the new interest in tattoos and piercings: it's a way of adorning the body, and to some people it's self-liberating."

But he says we need to grasp that society 3,000 years ago was highly honour-conscious. To do what was dishonourable was to invite censure and punishment.

"So, for instance, Ancient Greece was honest and perfectly open about homosexuality and accepted it in young men.

"But in other ways it wasn't the totally licentious place people sometimes imagine: individual city states could be quite restrictive."

Defining Beauty: The body in ancient Greek art is on at the British Museum until 5 July.

- Published16 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015