Marvel Avenged: From financial ruin to the biggest film franchise in history

- Published

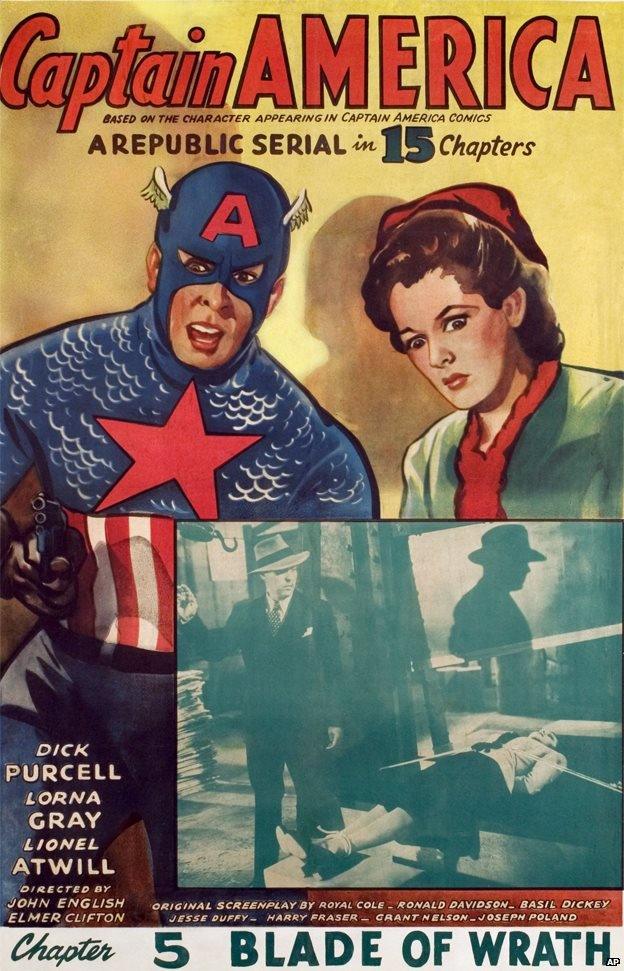

The series has covered period drama in Captain America, and Norse mythology in Thor

Fifteen years ago, Marvel had just escaped bankruptcy. This week, it could overtake Harry Potter as the biggest film franchise in history.

Avengers: Age of Ultron, the 11th movie in the "Marvel Cinematic Universe", hits UK cinemas on Thursday, a week before the US.

If box office predictions are correct, it will quickly become the franchise's third billion-dollar movie, pushing Marvel ahead of the $7.7bn made by the eight Potter films, and far beyond the likes of James Bond, Star Wars, and Lord of The Rings.

It's a huge turnaround for a company which, for decades, played second fiddle to its arch-rival DC Comics.

Captain America, serialised for cinema in the 1940s, was Marvel's last big screen success for 50 years

While DC scored major box office hits with Superman and Batman, Marvel's rich and diverse roster of characters were relegated to Saturday morning serials.

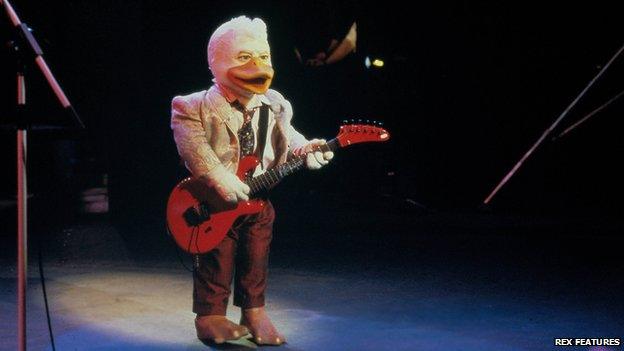

Its sole cinema venture in the 1980s was the risible Howard The Duck - a colossal flop that inexplicably featured an inter-species romance as its sub-plot.

Meanwhile, more obviously cinematic characters like Spider-Man and Captain America languished in development hell.

"Everyone was considering making Marvel movies but the budgets were just too high," says Sean Howe, author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story.

"Certainly before Terminator 2 there wasn't the technology to do anything in a convincing way."

Howard The Duck, about an alien stranded on earth, was derided as "noisy", "shrill" and "rubbish".

By the time the technology was available to bring Marvel's stable of superheroes to life, the company was on the brink of bankruptcy.

The comic book market crashed in 1993, thanks to a glut of underwhelming titles, and a crisis of confidence amongst collectors. Sales dropped by 70 per cent and Marvel was left heavily in debt. Shares that had been worth $35.75 in 1993 dropped to $2.38 in just three years.

The firm was only saved by a merger with toy company ToyBiz - whose boss, Avi Arad, was appointed President of Marvel's film division after a drawn-out boardroom battle.

Arad looked at the botched attempts to licence Marvel movies in the early 1990s - including a cheap, unreleased production of Fantastic Four, external - and made a decision: In the future, Marvel would commission its own scripts, hire its own directors and negotiate with stars. Then it would sell the whole package to a major studio, which would shoot and distribute the film.

"When you get into business with a big studio, they are developing a hundred or 500 projects; you get totally lost," Arad told the New York Times, external in 1996. "That isn't working for us. We're just not going to do it anymore. Period."

Launching in 2000, the X-Men trilogy proved Marvel's characters had a life beyond the comics

The strategy worked. Fox bought the X-Men, Sony took on Spider-Man and New Line made the Blade trilogy.

Only Marvel wasn't sharing in the profits. According to an article on Slate, external, the company made a mere $25,000 from the first Blade film. And, of the $3 billion that Spider-Man 1 and 2 raked in, Marvel saw only $62 million.

Worse still - as Hollywood jumped on the superhero bandwagon, it rushed out films based on Elektra, the Punisher and Daredevil which proved to be creative and commercial disappointments.

"Things got a little out of our hands," admitted Marvel president Kevin Feige on the company's own website, external. "That's when we started to think about making the movies internally."

Going it alone

So Avi Arad, along with chief operating officer David Maisel, went to Wall Street to get funding for an independent studio, making films based on second-tier characters the company hadn't already licensed elsewhere, starting with Iron Man.

"The funny thing about the plan is that Marvel used character rights as collateral," says Howe. "So if Iron Man was a disaster, they would give up a whole bunch of characters to the backers.

"That included The Avengers - but the way the deal was worded was that it didn't say who The Avengers were. And if you know comic book history, you know that The Avengers can be any of 50 different characters.

"So that was sneaky. They could have said, 'OK, you have the rights to The Avengers, so here's Jack of Hearts and the Two Gun Kid.'"

Iron Man was the first movie Marvel produced as an independent studio, and the launching point for the Marvel Cinematic Universe

Of course, Iron Man wasn't a disaster - but it was perceived as a massive gamble. A lesser-known superhero, played by "troubled" Robert Downey Jr in his first ever blockbuster lead role, directed by indie filmmaker Jon Favreau, it was far from a guaranteed hit.

But it delighted fans and critics alike, thanks in large part to Downey Jr's irreverent, wise-cracking portrayal of billionaire inventor Tony Stark - a refreshing change from Christian Bale's po-faced Batman.

The breezy tone set the template for the Marvel Cinematic Universe - where character and comedy are given equal emphasis to visual spectacle.

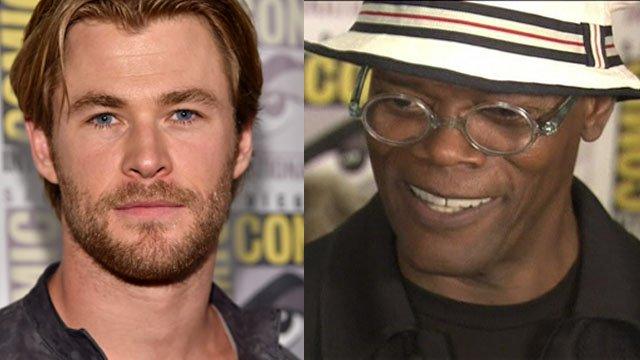

And, with the nerd-pleasing, post-credits appearance of Samuel L Jackson as Nick Fury, Iron Man teased the possibility of the first Avengers film.

"You think you're the only superhero in the world?" Fury asks, as he starts the process of building the superhuman supergroup.

"Mr Stark, you've become part of a bigger universe."

That universe now encompasses 11 films, seven TV series and a slate of movies planned until 2020. Each inter-cuts with the other, with a narrative arc plotted by a "brain trust" of Marvel producers, led by 41-year-old Kevin Feige.

"Logistically, it's a miracle that it's occurred," says Downey Jr. "But there was a plan for that miracle, so I hand it to them.

"It's kind of like kicking off a concert but you have no idea they want to turn it into Coachella. I'm humbled by the kind of folks that can have a masterplan like that."

The continuing storyline is what makes the franchise so special - and so successful - says Howe.

"Not just because each movie is an advertisement for all the other movies, but because it gives the narrative a complexity you can usually only get in serial television and comic books."

"And Marvel have got a better head start on marketing their movies than anyone else. If you think about the other movies that'll come out in 2018 and 2019, nobody's even got the ideas for them yet."

Age of Ultron adds Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver to the franchise's ever-expanding roster

"I think they have a unique advantage as a franchise," agrees Joss Whedon, director of the two Avengers films, and a creative consultant on Marvel's overarching plot.

"The Harry Potter movie was one thing, James Bond is one thing. But this can take disparate franchises and make them part of the same spreadsheet.

"All of the characters bring a unique energy - Thor is very different from Cap[tain America], who's very different from Iron Man - and when you put them together what you get is humour and conflict and all the other things you would hope for.

"It has the advantage of not being one thing, but being a little bit of everything."

Robert Downey Jr on enduring appeal of Marvel

Particularly after the success of last year's Guardians of the Galaxy - a risky venture, based on a lesser-known comic starring a talking raccoon - it feels like Marvel is unstoppable.

"Right now, it seems like its limitless, which should be disconcerting," says Downey Jr. "It's become bigger than the people or the filmmakers. There is a calling for this type of entertainment right now."

But Howe says Marvel's history holds a warning for the future.

"The narrative snowball of Marvel - the way that everything accumulates - means it gets bigger and more popular but also more unwieldy," he says.

"That happened in the comic books. With all the crossovers, everything became completely uninviting to the new fan. Eventually, Marvel had to hit the reset button and start over again, because you couldn't hold all of it in your head.

"Ironically, that could be the biggest danger to the success of the movies. There are so many storylines that you have to navigate in telling this bigger story, that eventually fatigue sets in - especially with people who are not already 100% on board.

"There's a lot of significant others being dragged to these movies who are going to rebel."

Avengers: Age of Ultron is in cinemas now.

- Published28 July 2014

- Published10 February 2015

- Published7 August 2012

- Published6 May 2012