Trying to shine at Venice

- Published

Helen Sear of Wales is exhibiting large-scale video installations and stills photography

So far Sarah Lucas has received all the attention, her giant phallic sculptures overshadowing the exhibitions presented by her fellow Brits. Which is fair enough, she is in the main British Pavilion, after all. But now she's had her moment in the Venetian sun, it's time to shine a light on the work of her compatriots.

Helen Sear is here representing Wales with a collection of works that couldn't be further from Lucas's in-yer-face seaside humour. This is an artist who prefers the romantic and elegiac.

The exhibition takes place in a suitably poetic venue, the beautiful Santa Maria Ausiliatrice, a church and former convent, a short walk from the teaming hoards dashing in and out of the main national pavilions in the Giardini.

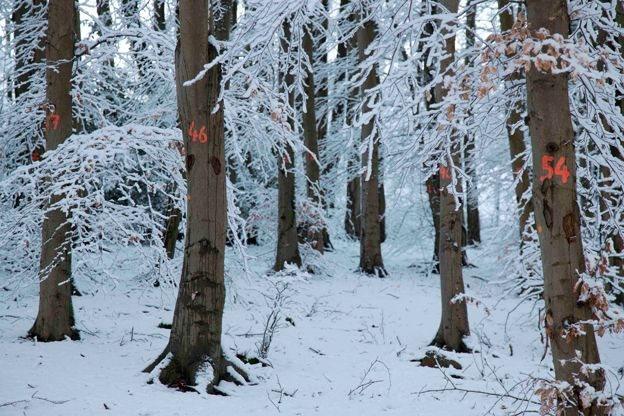

Sear has produced a series of gentle, atmospheric films and photographs that explore the ethereal and mystical beauty of the landscapes she has spent the last 30 years exploring in her adopted country.

She tells me how grateful she is for having such a high-profile platform on which to show her work. Artists from Wales, she says, struggle for the same level of attention enjoyed by those living in England and Scotland.

Graham Fagen is representing Scotland

Fagen explores themes of identity, commerce, slavery and consciousness

I'm not sure the Glasgow-based Graham Fagen, here in Venice representing Scotland, feels that he generally receives an overwhelming amount of attention. But he is this week. The Scots have rented a splendid 16th Century Palazzo in the north of Venice to show his work. It's quite a hike from where the majority of the action is taking place, but worth the effort.

Fagen is exploring themes of identity, commerce, slavery and consciousness. There's a rope in the shape of a tree which he has cast in bronze. A room displaying a series of Indian ink drawings made by the artist feeling his teeth with his tongue. And a final space in which he has installed an effective and affecting four-screen video performance of a poem by Robert Burns called The Slave's Lament, with vocals provided by reggae singer Ghetto Priest.

Chris Ofili is showcasing five new canvasses

Meanwhile, back in the Giardini, there is the centrepiece of the entire event: the exhibition All The World's Futures, staged in the Italian Pavilion. It's a maze of art and ideas that have been awkwardly corralled into an overarching left-of-centre geo-political theme of 'oh what a mess we're in'. Frankly, it doesn't wash in this environment. The truth is the Venice Biennale is an entertainment for the super-rich and hyper-cool.

But that's not to say that the show doesn't include some good work. There's a memorable group of skull portraits by the South African-born, Amsterdam-based artist Marlene Dumas. An excellent Hans Haacke semi-retrospective, and five huge new canvasses from the Turner Prize-winning artist Chris Ofili.

These I like, a lot. His work has moved on from the lumps of dung and cuttings from pornographic magazines that so upset New York's Mayor Giulani in 1999. The artist's admiration of Matisse and Klimt are still evident, as is - it seemed to me - an interest in William Blake. But these are just influences informing an artist that has developed his own, very distinct, and resonant voice.