The complex world of art sales

- Published

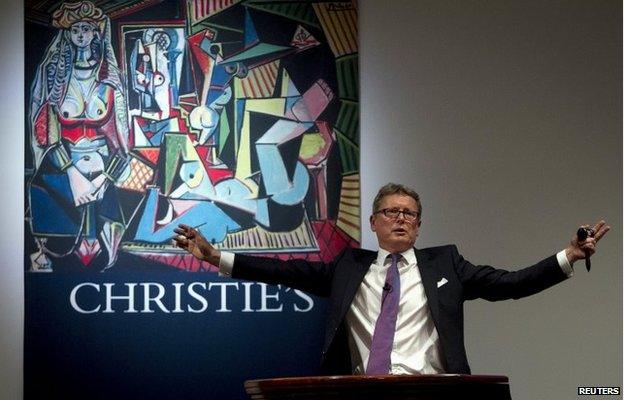

Auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen calls for final bids on Pablo Picasso's Women of Algiers

So Picasso's Women of Algiers (version O) has been sold for a record-breaking sum - going for $160m (£102.6m) at Christie's in New York.

Other than the high price, the transaction appeared fairly straight-forward. There's a seller, an (anonymous) buyer and an auctioneer to conduct proceedings.

But the opaque nature of the art world means trophy sales, such as the one last night in New York, are rarely that simple.

The auction houses are desperate for top-quality product and will go to great lengths to secure grade A works for their most prestigious sales. They might, for example, waive their fees for selling the work.

On occasion, they may even offer a guaranteed price to the owner, whether the work sells or not.

This, though, is a very high-risk practice. So they can offset the risk by arranging for outside investors to underwrite the guarantee. Anybody who does this will want a substantial slice of the profit, should the work sell for more than expected.

Can the third-party underwriter also bid at the auction, potentially driving the price up? Yes, they can - although the auction house will make clear that there are bidders with a financial interest taking part.

The irony is, that when it comes to these major sales in this red hot market, it's not so much a case of buyer or seller beware - it's the auction houses who need to be careful as they take on greater risks with reduced margins.