Remembering Rosalind: Sister recalls DNA pioneer brought to stage in Kidman play

- Published

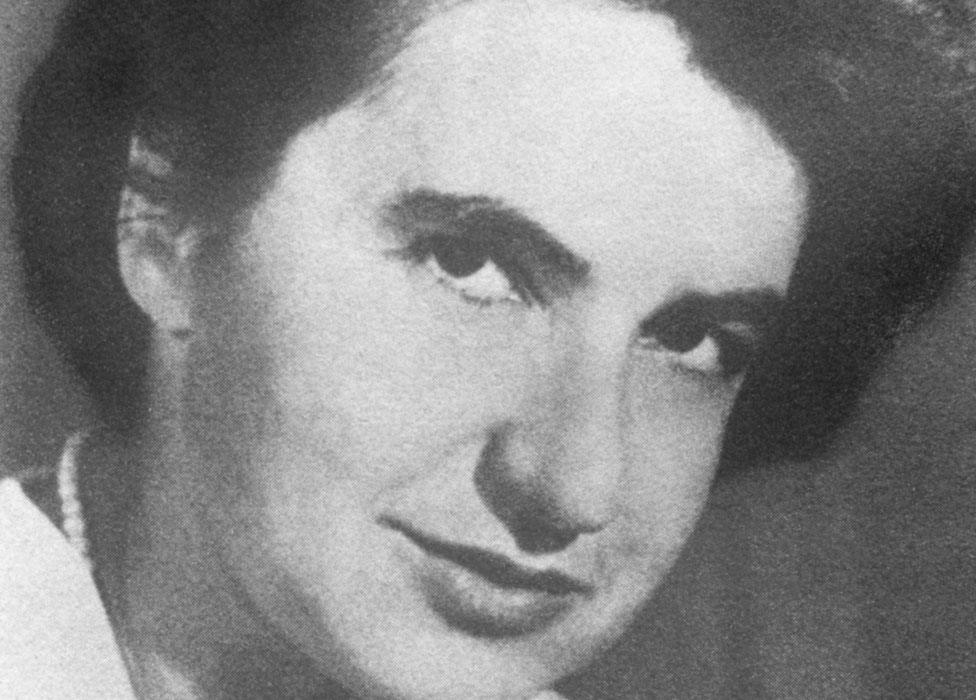

Jenifer Glynn said Rosalind "never saw herself as a victim"

When scientist Rosalind Franklin, who helped discover the structure of DNA, died in 1958 she was largely unknown. A play about her life starring Nicole Kidman is now on in London, but Ms Franklin's sister warns against seeing her as an undervalued victim.

It is 57 years since Jenifer Franklin (now Jenifer Glynn) lost her elder sister Rosalind to cancer. With interest in Rosalind now so great, Jenifer has published an intimate memoir of growing up with the bright, sometimes difficult girl who became an emblem of female attainment in science and medicine.

Jenifer still has copies of Rosalind's letters home, from early childhood through to her death at 37.

"Holidays and Travel is a big section because my sister always loved travel - especially to France and the mountains. Her life was far more than just work, which people at times assume."

Rosalind Franklin always wanted "proof" of facts, her sister said

Between 1951 and 1953 Rosalind Franklin worked, largely unhappily, at King's College, London. She was researching the structure of DNA. At the time the initials were meaningless except to a tiny core of specialists.

Today deoxyribonucleic acid is recognised as containing the vital genetic data which controls the development of living beings. Some consider DNA the key to existence. In 1962 three of Rosalind's fellow researchers - all male - shared a Nobel Prize for their work on DNA in London and Cambridge.

No-one can be considered for a Nobel Prize posthumously. So in that sense it's not true, as some have claimed, that Rosalind's work was ignored in favour of Maurice Wilkins, Francis Crick and James Watson (the only one who remains alive).

But was she quietly written out of the story? And was that made easier because of her gender?

'Love of argument'

Rosalind had been born in London in 1920. The family lived in Notting Hill but Jenifer Glynn says the area then wasn't as grand as it is now.

"Father was a banker and we had a house in Pembridge Place. But it wasn't quite how it sounds today. We had wealthy grandparents certainly, but we weren't rich.

"We were a family which debated things. We discussed events in a way I suspect most families now simply don't. So Rosalind grew up with a love of argument.

"My mother said that when my sister was told something, even when she was very young, she wanted proof. It's a scientific trait. I remember her being extremely honest with a tremendous sense of justice.

"We were a Jewish family and very consciously so. With all that was happening in Germany my father was involved in helping refugees. When Rosalind went to Cambridge University (in 1938) she was disappointed at first to find so many people politically unaware. She was of a left-wing disposition though not hugely active politically."

Kidman has said it was "an injustice" that Franklin was not recognised during her lifetime

As the letters record, after World War Two Rosalind went to work in France. "She was lucky to meet French scientists who invited her to work in their laboratory learning the techniques of X-ray crystallography." She later applied that skill in her work on DNA.

Jenifer is aware that some have sought a romantic motive for her sister's four years in France.

"There is nothing I know of at any point of her life which suggests a romance. Rosalind died young and she had found no-one she wanted to marry or to spend her life with. I know that may disappoint people but it's the truth."

The lack of a sweeping love-story is one of the factors which the American playwright Anna Ziegler contended with, writing her hit play Photograph 51.

It was commissioned in 2008 by a small theatre near Washington DC. Now the presence of Nicole Kidman in Michael Grandage's new production in London has brought fresh attention to Rosalind Franklin's story.

'Liberties with facts'

"Rosalind was a fascinating person who succeeded against the odds," Anna Ziegler says. "In the 1950s it was hard to be a woman and be a top-level scientist. She played a major role in what's arguably the biggest discovery of the 20th Century but that role was never sufficiently acknowledged.

"But the play isn't obsessed with the Nobel Prize issue. I've been looking at the play again for London and the more I work on it the more fascinated I become by the personal questions.

"Certainly the play is about the race to identify the structure of DNA, which was going on in other countries too. They were real events but I've taken liberties with the facts: it's not a documentary."

The reshaping of reality extends to a focus on Rosalind's friendship with her American colleague Don Caspar (who's still alive at 87).

Some scientists consider DNA to be the key to existence

"I have invented a certain amount but I didn't create some fiery Hollywood romance for Rosalind. But there were characters who loved her and I think the story is much the stronger for it."

Anna Ziegler's play goes into the controversial area of the extent to which Crick and Watson's research benefitted from Rosalind's work with X-rays without her knowing it. The play's title comes from a crucial image of 1952 which revealed the form of DNA more clearly than ever.

Director Michael Grandage says that part of the play provides what he calls "the thriller element".

"It helps draw the audience in. But there are other things which attracted me to the play. There was the fact, which I happily acknowledge, that I was looking for a new play to offer Nicole Kidman a huge and demanding central role to bring her back to the theatre.

"But there's a fantastic human story here. Audiences want to see characters and events on stage which in some way they identify with.

"Anna has written a very good play about a very intelligent woman who finds it hard to communicate - many people will relate to that. Rosalind is so fixated on her craft and mission that she finds it very hard to engage emotionally with other people.

"In fact that's what you're looking for in almost any play: the human emotion at the centre. I need to know that the narrative will touch people."

'Try a bit harder'

Jenifer Glynn has read Photograph 51 but has avoided seeing it. "I know that any play or film has to change the facts of a life to make a story work. But I think I'd rather not see my sister on stage."

After two unsatisfactory years at King's, Rosalind moved to Birkbeck College, London. Jenifer recalls that her sister found her work and colleagues there more congenial.

"But all her career my sister thought that as a woman scientist she had to try a bit harder. Undoubtedly she could be hard to get on with at times. Perhaps she suffered because Crick and Watson were prepared to go out on a limb - Rosalind wanted to be terribly sure of her facts before going public.

"I suspect that as a woman she was given less room to experiment and fail. But Rosalind never saw herself as a victim.

"People want her to be a feminist icon but one has to accept that when she died in 1958 there were still only the first stirrings of feminism. You can't rewrite the history of a whole era. But now Rosalind has become a public figure, in the way we could never have imagined."

So do plays and biographies and TV programmes threaten to take the memory of Rosalind away from her family?

"No. It's marvellous that for large parts of her life Rosalind wrote to our mother weekly. I have that correspondence. It means I can know and understand my sister, perhaps even more than when she was alive."

- Published7 September 2015

- Published23 April 2015