The tragedy and gaiety of David Jones

- Published

Jones' name (circled) is on a memorial to British poets of World War I in Westminster Abbey

David Jones found critical acclaim both as a painter and a poet and wrote an epic poem about World War I, yet little of his work is familiar today. Can two new exhibitions in Sussex return the artist-writer to the mainstream?

Thirty years ago, when poet laureate Ted Hughes unveiled a memorial in Westminster Abbey to the British poets of World War I, 16 names appeared on the stone. David Jones' was among them.

Compared to the likes of Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen or even Isaac Rosenberg, Jones was a less obvious inclusion. By the time he died in 1974, though, he had created a body of work much admired by critics.

As a writer, Jones was known for In Parenthesis, an epic war poem that came out in 1937. It's a complex work about more than just the war he had fought in as a young man.

The poem's reputation grew when the BBC produced a radio adaptation in 1946, remade two years later with the young Richard Burton in the cast, while admirers of his writing included TS Eliot and WH Auden.

Art historian Paul Hills is co-curator of David Jones: Vision and Memory, external, an exhibition that opens this weekend at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester. His love of Jones' visual art began during his student years when he was introduced to the artist, then 73.

"I visited him around ten times in Harrow, where he lived in a residential hotel," says Hills. "He had had health problems ever since his first breakdown in 1932 and he was agoraphobic - largely he was confined to his room. So he got a reputation as a terrible recluse."

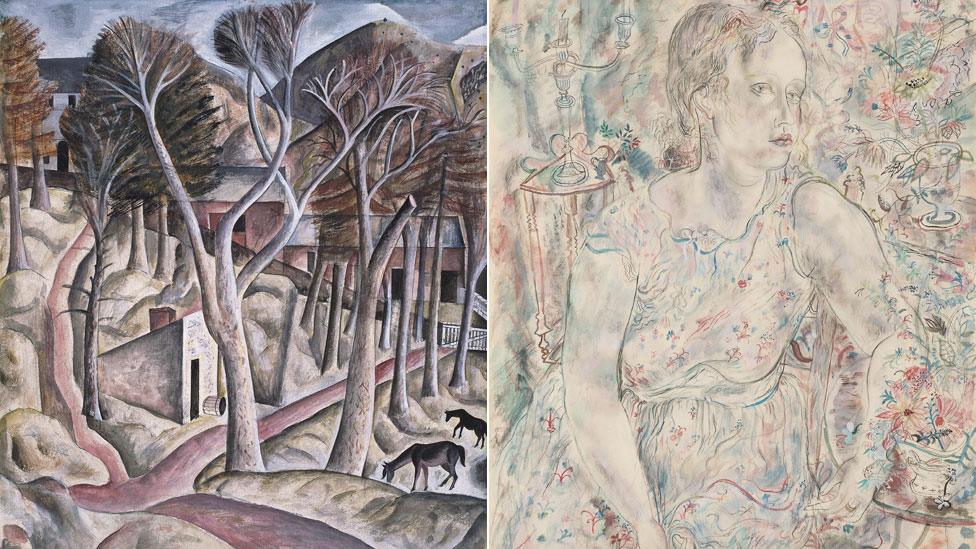

Capel-y-ffin in Wales (left) and one-time fiancee Petra Gill were among Jones' subjects

Jones has been written of as having a deep depressive streak, but Hills says that is not the whole story.

"The David Jones I knew could have the most wonderful smile. He was supremely alert and was extraordinarily welcoming and had a real gift for friendship.

"He loved having visitors and he could move from solemnity to gaiety with great speed: there was an impishness to him. I think all that is reflected in the artwork in the exhibition."

The show's other curator is Ariane Bankes, who says that while there has not been a major Jones show for 20 years, "it would be wrong to call him forgotten".

"But we both felt the time was right to reintroduce him to a wider audience," she goes on, saying people "may be surprised what they find."

"It's true that not many people under 40 know much about him," says Professor Hills. "But I've noticed that when younger people are introduced to his work they often love it.

"Contemporary culture seems to share his taste for the mythological - it shows up in films and in the books people buy. David Jones was fascinated by Welsh history and mythology and he loved Arthurian romance."

One of the most personal paintings in the show is The Garden Enclosed (1924). It shows David Jones with Petra, the daughter of artist Eric Gill.

A discarded doll can be seen in The Garden Enclosed, which shows the artist with Petra Gill

Jones was engaged to Petra Gill for three years. Ultimately, though, she called off the engagement and Jones was never to marry.

"It's a powerful image," says Ariane Bankes. "It shows a man and a woman in a form of embrace, but she appears to be pushing him away.

"On the ground lies a discarded doll, which you could interpret as the end of childhood and of innocence. There's a slightly hallucinatory quality to the image and he's playing with the perspective.

"Overall it feels like the work of someone very undecided. It's not a happy painting, but it's a gem of a work and very original."

Also in the exhibition is a beautiful watercolour of Capel-y-ffin, near Hay-on-Wye in Wales. Eric Gill ran a workshop here in the 1920s, with Jones a sort of disciple.

The emotions that surrounded Jones' time there were intense. Yet Paul Hills says it would be wrong to associate Jones' work with non-stop emotional trauma.

"Since he was a young boy he'd adored sketching and painting animals," he reveals. "There's a lovely sketch of a dancing bear from when he was only seven, in which you already see a talent."

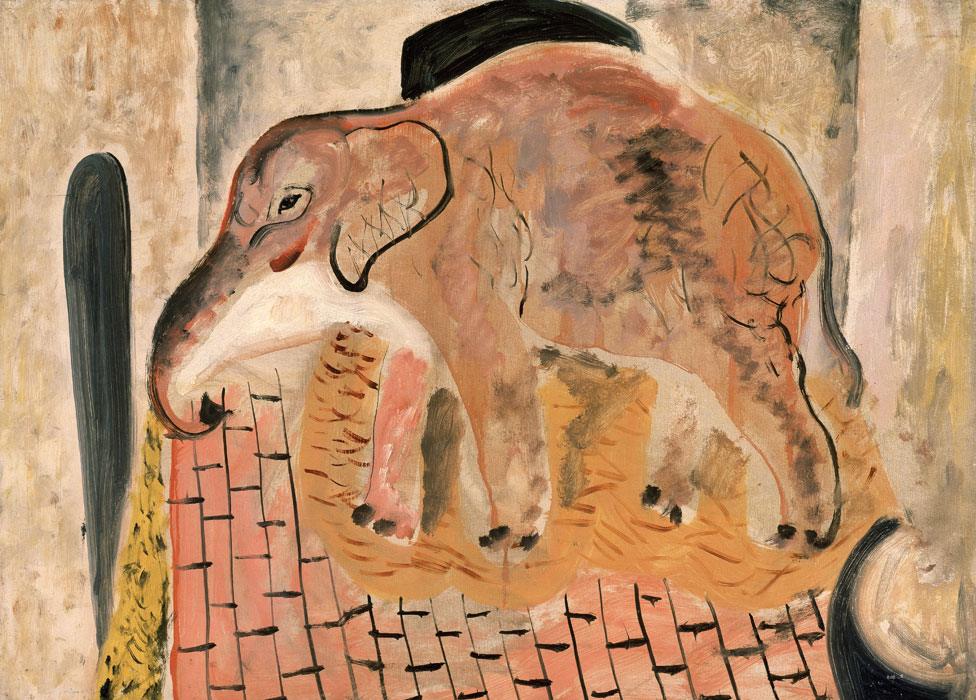

As well as the main exhibition in Chichester, a smaller display at the Ditchling Museum, external in East Sussex concentrates on Jones' animal images, including a delightful elephant he painted after a visit to London Zoo in 1928.

Jones' Elephant is one of the works on display in Ditchling

For much of his life Jones faced psychological challenges. Yet Paul Hills says, in some ways, he was a tough character.

"He volunteered for the First World War and when he was in the trenches he volunteered for missions into No Man's Land.

"In some way he relished the war and the camaraderie it offered. But undoubtedly later in life the war contributed to his problems, which at times stopped him painting."

Ariane Bankes thinks Jones came to terms with his depression and used it in his work. "In those days people might have used the word neurasthenia," she says, an alternative term for shell shock or post-traumatic stress disorder.

"In fact, David Jones called that state of mind 'Rosy', which is the middle of the word neurosis. But he was never totally bowed down by it."

Paul Hills says one of the main aims of the Pallant House show is to reveal the variety of Jones' talent. "There's tragedy, comedy, a witty gaiety, but also an intense solemnity.

"I know that sometimes confuses people, but I think it's part of his brilliance".

The exhibitions in Sussex are not the only sign of a revival of interest in David Jones. In May next year, Welsh National Opera will premiere an opera based on In Parenthesis.

David Jones: Vision and Memory is at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until 21 February. The Animals of David Jones is at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft until 6 March.