Enya on her new album, living in a castle and the international appeal of her music

- Published

Upon meeting Enya it is almost a shock to hear her speak with one voice.

On record, she is eternally a choir - with hundreds of cascading, ethereal harmonies recorded painstakingly over months in the studio.

But perched neatly on a sofa in London's Dorchester Hotel, Enya is softly-spoken and homophonic.

She chats happily about Ireland and her family, as though we were old friends. The only glimpse of megastardom comes when she casually refers to her "castle".

Because Enya lives in an actual castle, to the south of Dublin, which she bought for £2.5million in 1997 and named Manderley after the house in her favourite book, Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca.

"The nephews and nieces love the old castle," she grins, "running up and down the spiral staircase."

The Irish musician, born Eithne Ni Bhraonain, can afford to live in luxury. She has sold more than 80 million albums around the world, while remaining enigmatically above the fray of the music industry. Her public appearances are so rare she makes Adele look like Lady Gaga.

"I find that fame and success are two different things," she says. "You can have success with the music and then have the choice of how famous you want to be.

"Coming from Donegal, you have your feet firmly on the ground, and I always focused on what I was comfortable doing. And, in that regard, I always focused on the music."

Her profile is so low, she admits, that a fan once confessed they didn't know whether she was a band or a solo artist. In fact, they weren't even sure what her name was.

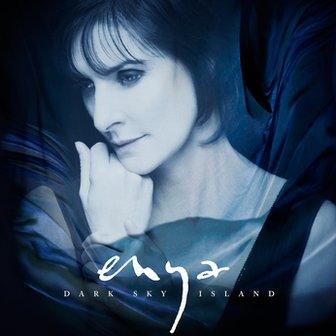

Dark Sky Island is Enya's 9th studio album

"But they enjoyed the music and that, to me, was really important."

Despite appearances, Enya's music is a group effort. She makes all of her albums with husband and wife team Nicky and Roma Ryan - who act as her producer and lyricist respectively.

More importantly, it was the Ryans who discovered and nurtured Enya, encouraging her to leave Irish folk band Clannad and forge a solo career.

It was also Nicky who helped realise the singer's genre-defining sound - a mixture of Celtic folk, early sacred music and world music, upon which Enya's vocals are layered hundreds of times to create vast, breathy choruses that seemingly emerge from the mists of Irish history.

Lazily, it has been called elevator music or "new age" - a term which Enya has dismissed as "marketing" - but there is something precise and affecting about Enya's vocal performance which explains her ability to sell millions of records around the world.

And yet, you can't help but imagine that her recording studio is littered with candles and patchouli oil.

"Studios usually are a bit dark and a bit smelly but not our studio," she concedes. "It is actually on Nicky and Roma's grounds and they built it from stone, so it looks like an old church."

The painstaking process of piecing together a new Enya record takes an average of three years - so the trio keep strict office hours during recording.

"I go in every morning. It's about seven minutes away from my home, if you're driving. And there are these beautiful wrought iron gates at the entrance of the studio. And they have our names on the gates.

"Once I arrive at the studio, the focus is totally on music and we work from 10 o'clock to half five or six."

Why does it take so long?

"Time is the important factor," she says. "We work on one song and then set it aside for two or three months. When you eventually go back, you can be a critic for a short time because it's new to you again.

"Is this arrangement working? Is it enhancing what the melody is about? Are the lyrics right? And sometimes we just take it all back to the melody again and start it all over again."

Golden microphone

When Enya recorded her first, self-titled album in 1986, studio technology was much more primitive.

The singer would record 24 vocal takes onto a multi-track tape. They would then be merged onto a single track, with the rest erased to free up room for even more vocals.

Nowadays, digital technology allows hundreds of tracks to be recorded, almost without limitation - but Enya says she doesn't use any modern tricks, like cutting, pasting and auto-tuning, to speed things up.

"It's still live voices," she insists. "With sampled voices, there isn't that emotional feeling. So if I'm layering my voice, I will sing for the duration of four minutes and then layer it for the hundreds of voices."

Fittingly, she says, those angelic harmonies are recorded into a "golden microphone".

"It is actually gold, or gold-plated," she laughs. "It gives a very, very bright sound. So you hear even more of the air and the elements in your performance."

But the microphone lay unused for four years after 2008's A Winter Came album.

"I didn't know what to do musically next," says Enya. "I felt I needed a break, and I felt the music needed a break as well.

"So I took three years where I didn't go back to the studio, I didn't write any music and basically travelled.

Enya performed Orinoco Flow, her breakthrough hit, on Top Of The Pops in 1988

"Then, at the beginning of 2012, I felt the yearning. I missed it. I needed to go back to the studio and it was a lovely feeling."

Her travels inspired a new album, Dark Sky Island, whose first single is described as a "companion piece" to her breakthrough hit Orinoco Flow.

Where that song was an itinerary for the most expensive gap year of all time ("From Fiji to Tiree and the Isles of Ebony / From Peru to Cebu, hear the power of Babylon"), Echoes In The Rain is about "the journey home and the excitement and nostalgia and the memories of home".

So why return to the themes, and the sound, of Orinoco Flow after 25 years?

"It was not intentional," she says. "It was just a natural progression. And maybe it was just because I took the break.

"The chorus was the first I had written [after going back to the studio] and I felt like it wanted to embrace something positive. So talking about this journey home felt right. And it doesn't necessarily have to be about your home, it could be a place you love that you haven't been to in years."

The theme of travel and making journeys - both emotional and physical - came to define the whole album; which is named after Sark Island, in the English Channel, which has officially been designated a "dark sky preserve", meaning it is free from light pollution.

"There are a lot of dark sky areas around the world - but this was the first island," Enya explains.

"The 600 people who live there have even decided not to have any cars to combat the pollution of the light. And, from what I have heard, the night sky there is unrecognisable to us - because of the vastness of the stars that you will witness.

"And I loved the story about the island and when I went back to the studio in the spring of 2012 that was my first inspiration."

Musical home

Has she ever wondered why her music, which is so rooted in the traditions of Ireland, has translated to countries as far flung as Brazil, Japan and Mexico?

"I have often asked people, 'does it matter that I'm singing in Gaelic, or I'm singing in Latin?' But they said that they can sense the emotional feelings within the performance of the song.

"And also it's very interesting that, with Irish music, there are a lot of minor keys and, in Japan especially, their music is also very much based on the minor. So I don't know if that is why they enjoyed the music so much?"

After all her travels, I wonder, where is home for Enya? Is it with her family, back in Donegal on Ireland's north-west coast? Or is it in that castle, overlooking Bono's house in Dublin?

"I think it's a bit of everything," she muses. "It's the people that you miss, as well as your physical home. The studio is very much a home, but a musical home. And because I travel so much, I have another home in the south of France. So home can be anything."

Enya's new album, Dark Sky Island, is released on Friday, 20 November.

- Published23 October 2015