Why Strictly dances to Russia's beat

- Published

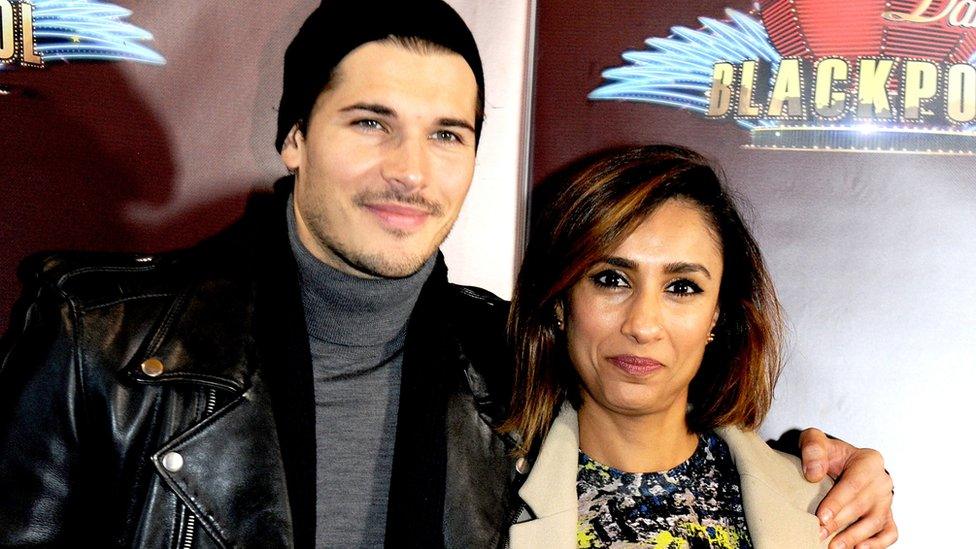

Gleb Savchenko joined Strictly in 2015

Why is it that Russian dancers are so prominent on Strictly Come Dancing, and so visible in many international competitions and dancing shows? Bridget Kendall, the BBC's diplomatic correspondent and former Moscow correspondent, has been investigating.

When Gleb Savchenko - one of the new Russian dancers on Strictly Come Dancing - turned 13, his grandfather asked what he'd like for his birthday.

"I said, 'I want dance shoes.' They were, like, $100 (£67)... And my grandfather said, 'Don't you want something else, something a boy would want - a bicycle? A skateboard?' But I wanted the shoes... So we went together and bought them, and I was really, really happy."

By this point, Savchenko had been dancing for five years and was already addicted to ballroom. It was the 1990s - a grim time in Russia.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many people had no jobs or tiny salaries. Savchenko's dancing career was a family enterprise. His grandparents and uncle helped pay for lessons. His father drove him two hours across Moscow every day for training sessions and two hours back again. His mother sewed his costumes and when he came second in a competition, took him aside and told him to try harder.

A decade earlier, in the Pacific port of Vladivostok in the far east corner of Russia, Kristina Rihanoff, another familiar face from Strictly, also started dancing young - at six-years-old. The competitive ethos of the Soviet Union meant children were always being pushed, or even groomed, says Rihanoff.

"You were sort of faced with the ideology that you had to be the best, to deliver for your class, for your school, for your country."

Gleb Savchenko has also danced on the Australian and American versions of Strictly

But dancing school was also fun, and she enjoyed the sparkle and glamour of the competitions - an escape from the grey world of the last years of the Soviet Union. A little older than Savchenko, she now recognises the limited horizons of her provincial Soviet childhood.

"You don't really understand living under the Iron Curtain, as a child. You just accept things around you, you don't really see. I think now I understand that everything foreign was acknowledged as propaganda."

So while they danced waltzes and foxtrots and cha cha cha, there was no samba from Brazil or Argentine tango. And jive from America, that Cold War enemy, was off limits.

Gleb Savchenko has competed in Australia and America's versions of Strictly Come Dancing

To keep abreast of new steps, dancers would seek out videotapes of big competitions. Rihanoff says she would study borrowed tapes for days to memorise all the routines.

Marina Tarsinov, a former national champion, learnt to dance in another remote part of the USSR, the central Asian republic of Tajikistan. She recalls the excitement of getting hold of a recording from that all-time Mecca of ballroom - Blackpool. Even though it turned out that the technician put the film in the wrong way round.

"It was in black and white and had no sound. But we were so happy to see actual dancing, and to learn from this recording - the style, the costumes, the hair, the dancing," she says.

"We watched it, and we even learnt something from this tape. But then we realised we had learnt everything backwards because he put it in wrong."

It was a Blackpool couple who first helped give ballroom dancing respectability in the Soviet Union. Up until the 1950s, the Communist government in Moscow discouraged it as too foreign and too reminiscent of the previous tsarist era whose every trace it wanted to erase.

Leonid Pletnev was one of the early pioneers of ballroom dancing in Russia

But after Stalin died, the political atmosphere eased somewhat. In 1957 Moscow hosted an international Youth Festival, which brought in young people from all over the world. Among them were Harry Smith-Hampshire and his partner Doreen Casey, the British European ballroom champions, who danced in front of an audience in the Kremlin.

"They did a show dance, and were invited to an audience with our general secretary and the Politburo. It was a big event and sped up the development of ballroom dancing in the Soviet Union," says Leonid Pletnev, another veteran Soviet ballroom champion who is now honorary president of the International Dance Union.

After that, ballroom dancing was on the list of permitted amateur hobbies offered by local so-called Palaces of Culture. But some Soviet officials still regarded it with suspicion. It remained a peripheral activity, neither banned, nor exactly celebrated, and sometimes even dangerous.

Pletnev recalls one competition held at night and in secret, to avoid trouble from officials.

"It was really a spy story, how we got to this Palace of Culture - sitting in the bus with curtains closed and then running inside. That was how far it could go. They called us 'agents', 'agents of counter-propaganda'. Now we can smile about it, but then it was not nice."

Kristina Rihanoff says she notices her teenage nephews and their peers are not as driven as she was to find success, as they have much more comfortable lives

Almost no Soviet dancers were allowed to travel abroad. In the 1980s Marina Tarsinov and her husband Taliat were among the lucky ones. By now national champions, they managed to get permission to go to Belgium - though only after one government official personally guaranteed that they would not try to defect. As a young married couple with no children, they were seen as prime candidates.

"One day when we were going to dinner," recalls Tarsinov, "we saw from the bus window a shop selling feathers. So we decided we would eat very fast and run back to this shop to buy the feathers (for our costumes).

"When we got back, the guy who gave the guarantee was almost having a heart attack: when he saw us running out, he thought we were escaping."

With the arrival of perestroika reforms in the late 1980s and the Soviet Union dissolution at the end of 1991, everything changed. Now Russian dancers could travel.

The Tarsinovs run a Fred Astaire Dance Studio in America

But while government restrictions had gone, the new obstacle was money. Pletnev recalls driving all the way from Russia to Blackpool, because he couldn't afford the plane ticket. In Germany he worked as a dishwasher. In Norway he acted as an odd job man for his Norwegian dance teacher.

"I cleaned his garden, I changed the wheels on his car, cleaned his studio. I got some money and paid him straight back for another lesson," says Pletnev.

But the post-Soviet era also brought an exodus of some of Russia's top talent. The Tarsinovs were early emigres who made their way to New York in 1992. At first they found the adjustment difficult.

In Russia the focus had been on training talent to create champions. In America dancing was a service industry, delivering entertainment to the public. Marina Tarsinov says they also found they were treated with suspicion, as unwelcome foreign competition.

Gleb Savchenko (front left) was a newcomer to Strictly Come Dancing in 2015

"We were very successful competitors and not everyone loved it. In some competitions they would not allow us to dance - they would ask for our passport and ask if we had legal papers. They would give us an empty envelope instead of prize money. People did a lot of things to us to show that we were not welcomed."

But those initial resentments evaporated. Now the Tarsinovs are well established, running one of the famed Fred Astaire Dance Studios, teaching a new generation of Americans - and Russians living in New York - to waltz and foxtrot. And the outflow of top Russian dancers, seeking fame and fortune abroad, continues.

Rihanoff also found her way to New York, via international dance competitions. She visits her mother in Vladivostok every summer, but has no plans to return to Russia.

Savchenko moved first to Latvia. A modelling career then took him overseas to Hong Kong and New York. Since he returned to dancing full time, he's been a professional dancer on the Australia and American versions of Strictly, and here in the UK, of course. He, too, has no plans to return to Russia.

So, if so much top talent has moved abroad, what of the next generation of Russian ballroom dancers? Will they benefit from the same level of dedicated teachers? Will they be as motivated to excel?

'What they live for'

Rihanoff says she notices her teenage nephews have a different mentality.

"It's much more relaxed and they are not driven because they have much more than we had. I would never say it was a bad time, because what we lacked in knowledge, we made up for in perseverance.

"With the little information we had, we worked hard to get ourselves to the best stage we could be. Now you can get clips from YouTube, you can travel, and you can get lessons from the best in the world. But it takes a special person to push themselves."

But Savchenko thinks there are still plenty of young Russians throwing themselves into dancing as a way to escape to something better.

"I'm sure there are people somewhere, in a small city, practising and dreaming to go out there and have a chance... and they are still watching the videos from Blackpool and trying to copy the routines. And that's what they live for."

A shorter version of this article originally appeared in this week's Radio Times.

Radio 4 will broadcast Bridget Kendall's Strictly Russian programme on 12 December at 1030.

- Published6 September 2015

- Published2 November 2015