Assemble help Turner Prize rediscover the art of controversy

- Published

Assemble drew up plans for a winter garden in one derelict house

Cows in formaldehyde. Lights going on and off. Elephant dung.

Throughout its 31-year history, the Turner Prize has revelled in selecting winners that prompt the question: "Yes, but is it art?"

This year, it has done it again.

But as the shock value has drained out of modern art, and as fewer artists can simultaneously tap into and taunt popular culture, the Turner Prize has been forced to look beyond the art scene altogether.

Until being nominated, this year's winners Assemble did not think of themselves as artists.

They were a group (numbering between 14 and 18) who had innovative ideas for architecture and design projects.

When the phone rang to tell them they had been nominated for the Turner Prize in May, they did not think it could be THE Turner Prize.

"The girl who took the call in the office thought it was for an obscure architecture Turner Prize that we had never heard of before," member Fran Edgerley told Liverpool's Double Negative art blog, external.

It was THE Turner Prize. They were nominated for the prestigious art award for their work regenerating terraced houses that had been boarded up for years in Toxteth in Liverpool.

They won the Turner Prize for their work in Liverpool's Cairns Street

A street market takes place on the first Saturday of every month

They worked closely with local residents and were familiar faces on the building sites in one of Liverpool's most run-down areas - far removed from a fashionable artist's studio.

But nor were they following the fashions and formulae of most architects. They brought an artistry to the process, lovingly fashioning low-cost fireplaces, tiles, fabrics and other interior fixtures and fittings.

They took part in a monthly community street market and even drew up plans for a winter garden that would take up the full height of one dilapidated house.

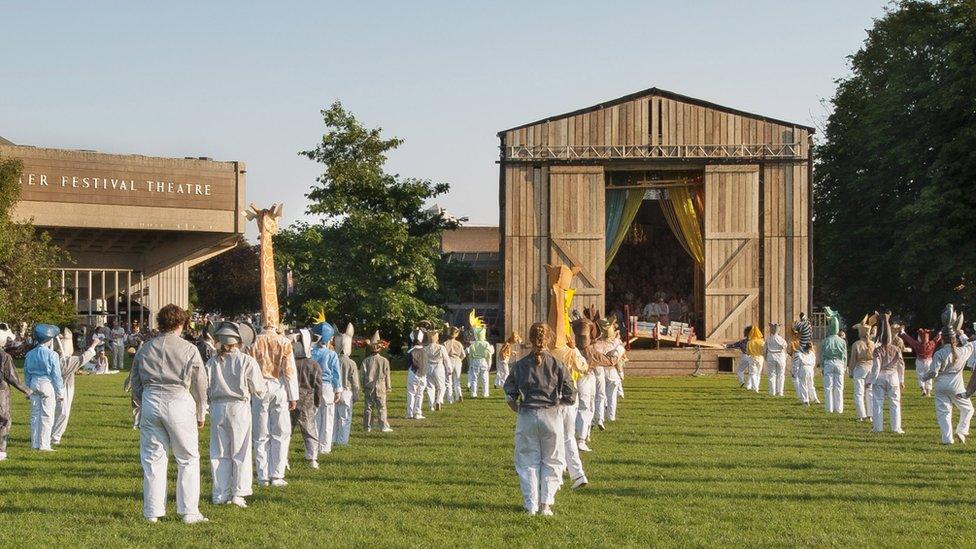

Assemble formed in 2010 and, as well as the Liverpool project, have turned a derelict petrol station in London into a cinema, converted a disused motorway underpass into an arts venue and built temporary theatres in Chichester and Southampton.

They have created an adventure playground featuring mud, scrap metal and campfires in Glasgow, are turning a former Victorian bathhouse into a new art gallery for Goldsmiths University and are erecting a huge climbing wall in Swansea.

Many members of Assemble studied architecture - but did not finish their training

Their work caught the attention of Alistair Hudson, director of Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, who was on this year's Turner Prize panel and has been Assemble's biggest champion.

Hudson has long been an advocate of "useful art" - art that plays a role in society and the community, rather than being reserved for a white-walled gallery.

He traces the idea back to William Morris, who believed in "art for all" and who designed wallpaper, textiles and tiles as part of the Arts and Crafts movement in the 19th Century.

Assemble, Hudson told BBC News arts editor Will Gompertz, fit into "a long tradition of art working in society".

He added: "You could perhaps look at Bauhaus, or the Omega Group, or the Arts and Crafts group as part of a long trajectory of artist communities or artist activists really trying to have a genuine impact in the way society operates.

"There have always been these different versions of art, and different art worlds in operation."

So what is the difference between an architect and an artist?

"I would argue there's maybe not a fine distinction," Hudson said.

"There's a graded line between the two. One blurs into the other."

Assemble designed a temporary theatre in Chichester

But that view is not shared by everyone.

The Daily Telegraph's art critic Mark Hudson told BBC Newsnight on Friday, external he did not see Assemble's work as art.

"It works very well as architecture," he said.

"Why bring it in as art? If you're just looking for stuff that isn't pretentious and is useful, why don't you nominate B&Q or Oxfam?

"It's great if art can be useful. But just because it's useful doesn't make it art."

There was not much actual art on the Turner Prize shortlist this year - perhaps an indictment of the state of British art.

'Anyone can create art'

Assemble were shortlisted alongside an avant-garde opera, a recreation of a supernatural study room and a lifeless installation comprising chairs and fur coats.

Against that competition, it was no surprise that Assemble won - they shone a light on our forgotten urban spaces and showed a way forward.

After the ceremony, Assemble's Joseph Halligan told Reuters the art world should not shut its doors on people like them.

He said: "I think the idea that art is something that can only be created by someone that declares themselves an artist is maybe not the best thing.

"I believe that anyone can create art, and art should be for everyone."

- Published7 December 2015

- Published7 December 2015

- Published30 September 2015