The underground sound systems of the UK's reggae scene

- Published

In 1973, the Notting Hill Carnival invited reggae sound systems to take part in its annual street party.

For many in England, it was their first encounter with these custom-made set-ups, which migrated to Britain from the Caribbean in the 1940s.

Created by rival soundmen and their crews, sound systems developed a distinctive British style - and a loyal following.

"Sound systems come in all shapes, varieties," says music historian John Masouri.

"Some specialise in dub, some specialise in MCs, or singers at the mic, some put the emphasis on the sheer weight of the sound and the tone quality.

"Some play the latest music, some play music from the past, whether it's ska or dub or roots music.

"Some are heavily inspired by Rastafari, others are more hedonistic."

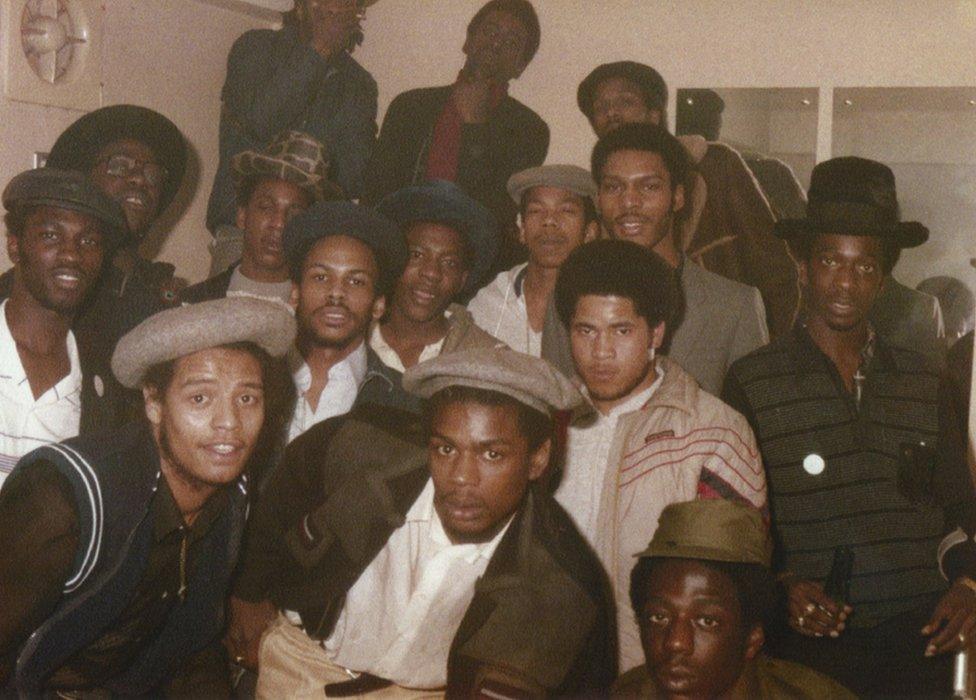

Birmingham's Wassifa Sound System established a nationwide reputation in the 1980s

A series of exhibitions in Bristol, external, Birmingham, external and London, external have documented the growth of sound systems in the UK.

At their peak, they could have stacks of speakers standing 12ft (3.6m) high, and at least as wide.

There would be banks of amplifiers plus turntables and microphones.

"There would be singers and MCs at the microphone - and a packed crowd of very enthusiastic people who knew exactly what was happening," says Mr Masouri, who worked on the exhibition Sound System Culture London, external.

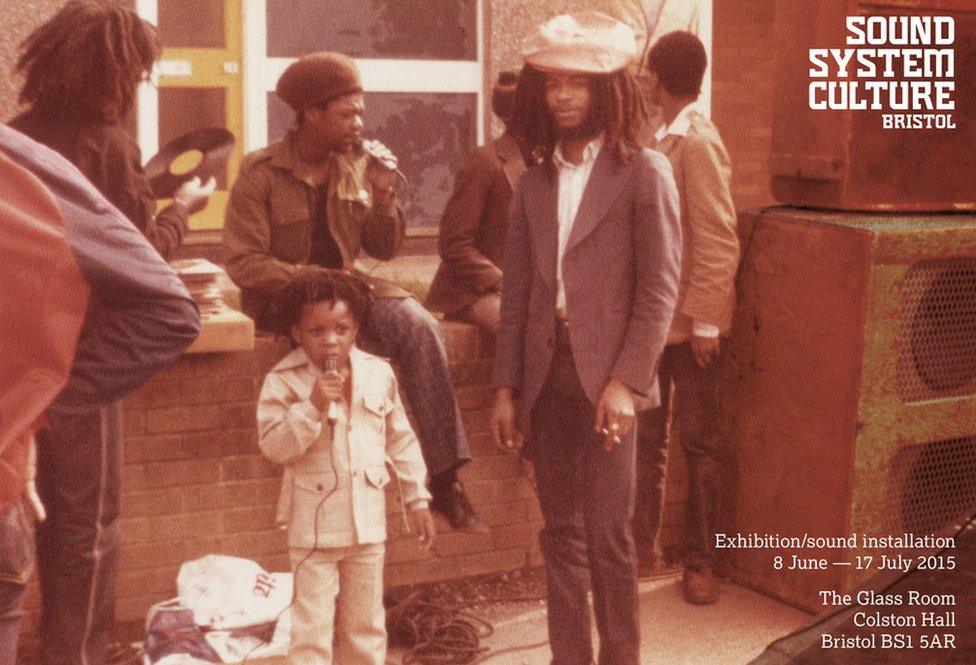

People gathered around a speaker box at a Birmingham community centre

What distinguishes sound systems from a disco, he says, is the crew that runs the set-up.

"You would have the owner and the manager, who would deal with all the bookings and collect the money," he says.

"You would have the amp-builder, who would build all the custom-designed equipment to certain specifications.

John Masouri spoke to World Update on the BBC World Service - listen to his interview here

"You would have the operator, who would make sure that the sound system was working properly.

"Then, you would have the selector, who chooses the music and actually puts on the records.

"And you would have the talent around the mic, who would keep the crowd happy and entertained.

"So it really was a team effort.

Some sound systems, such as Jah Shaka, seen here in Deptford in 1984, were inspired by Rastafari

"They started off as illegal house parties in basements and so on because Caribbean people coming to this country found pubs and working men's clubs unwelcoming environments.

"So they created their own spaces where they could enjoy themselves - initially to the sound of radiograms."

Former club-owner Newton Dunbar says: "We had to find ways of alleviating the stress.

"Naturally, people wanted somewhere where they could let their hair down and relax, and so we had to find ways of creating this.

"One of the ways was what we used to call a 'blues party' - a pay party held in a house.

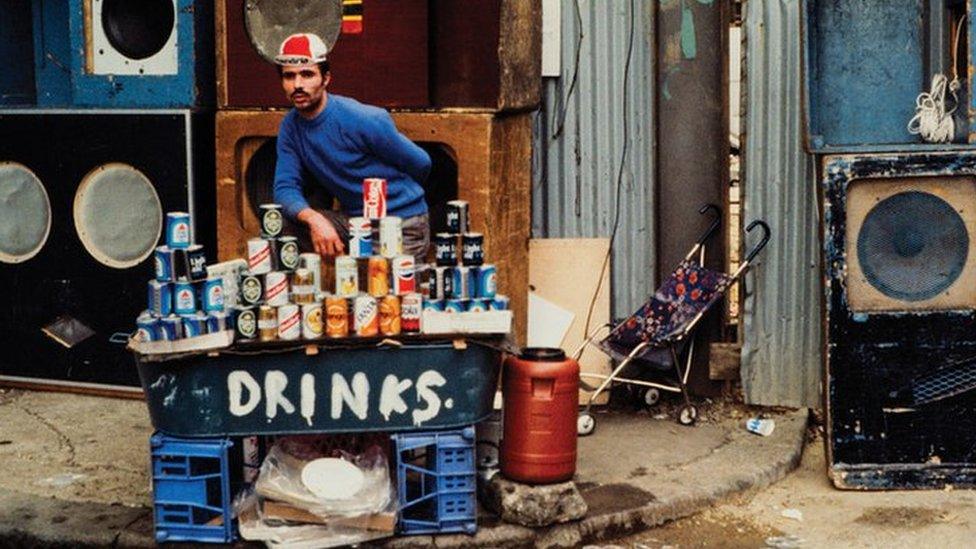

"A sound system would move their equipment into this house, and people would pay a nominal sum to enter.

"They would sell beer et cetera, and whatever they could think of for making a little bit of money."

Soundmen like Lloyd Coxsone created their own systems with custom-built equipment designed to convey the kind of sound and power they personally wanted.

Coxsone came to London from Jamaica in 1962 and settled in Balham. "There was a little place that West Indian people go and play dominos," he recalls, "and there was a little sound (system) there called Queen of the West.

"I started to ask the selector if I could spin a few tunes. He said when his turn come to play the domino I could spin a few tunes, so when his turn came to play domino I was spinning a few tunes on the sound and automatically I took that little sound over."

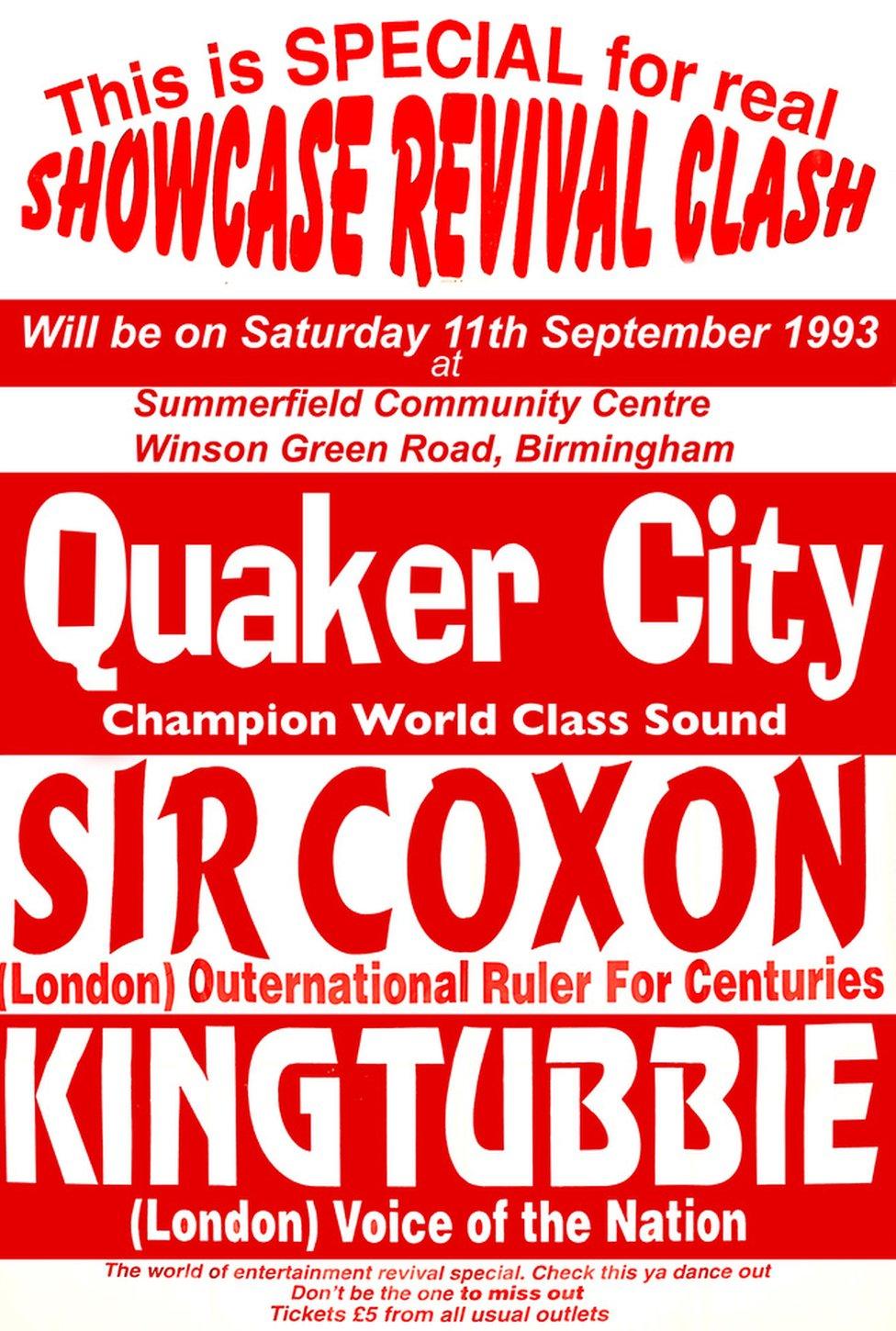

Coxsone went on to build his influential sound system, Sir Coxsone Outernational, in 1969. He remembers listening to other sound systems working in London at the time, such as Metro Downbeat, Daddy Young, and Neville the Musical Enchanter.

"But the difference with Sir Coxsone sound from all of these sound," he says, is "these sound was very good sound in London - but they weren't going anywhere.

"When I come with Sir Coxsone sound I travel to Bristol, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds - I travelled the breadth of the United Kingdom. They weren't slick venues, but the vibe was very nice. And hundreds of people turned out, because they wanted the entertainment.

"Then the other sounds started going around as well after we travelled around the place."

The cities Coxsone visited had their own thriving sound system scenes, but London was the major hub.

"All of the top Jamaican artists, producers, engineers, the major figures of the Jamaican scene, all came to London," Mr Masouri says.

"A lot of them lived in London for various periods of time, including Bob Marley, Dennis Brown, Gregory Isaacs, Jimmy Cliff, and so the bonds were much stronger in London than anywhere else in the country.

"The heaviest, the most impressive sounds systems tended to come from London.

"It was in London that the sound systems emerged that could not only match the top Jamaican sound systems but even surpassed them in certain aspects."

"We’ve inspired a generation of sound systems worldwide" - Lloyd Coxsone founded one of the UK's most influential sound systems, Sir Coxsone Outernational

And it was a massive endorsement if a sound system could attract Jamaican artists.

Mr Masouri says: "It's the equivalent of if you invented a country-and-western scene in Yorkshire, and Willie Nelson thought you were doing OK, you'd know then that it's pretty much a thumbs-up.

"And you also have to remember that when the big singers came in from Jamaica - I'm not really talking about Bob Marley or singers like that so much, but the dancehall artists, the MCs - you didn't go and see them at conventional venues, you saw them on sound systems.

"So you would have to go and see Sir Coxsone, for example, to see Josey Wales or Junior Reid or Nitty Gritty or Tenor Saw when they arrived in the UK - that's where you would see them."

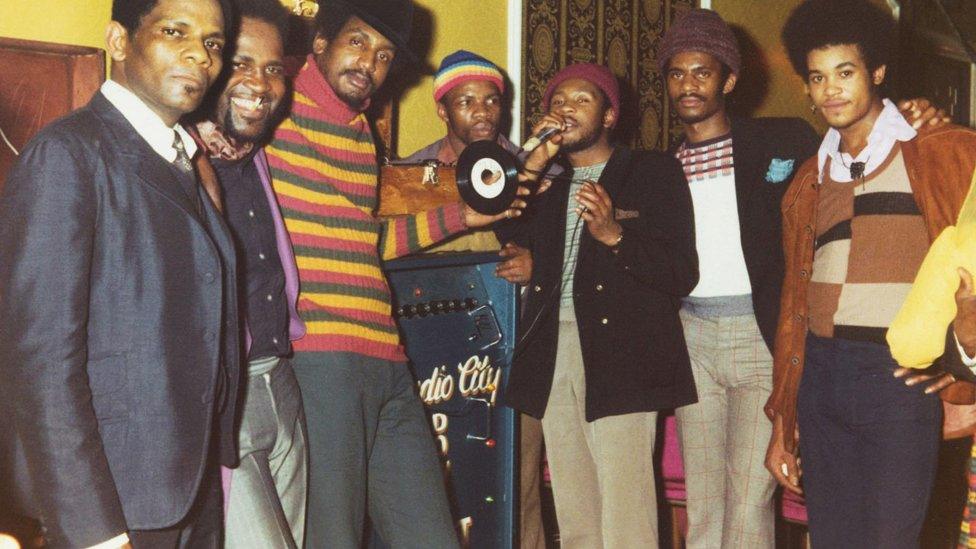

The Studio City Crew nurtured future members of UB40

The 1980s saw a shift, with a new generation of sound systems emphasising the MCs and singers grouped around the microphone.

And UK sound systems really came into their own, even influencing the Jamaican scene.

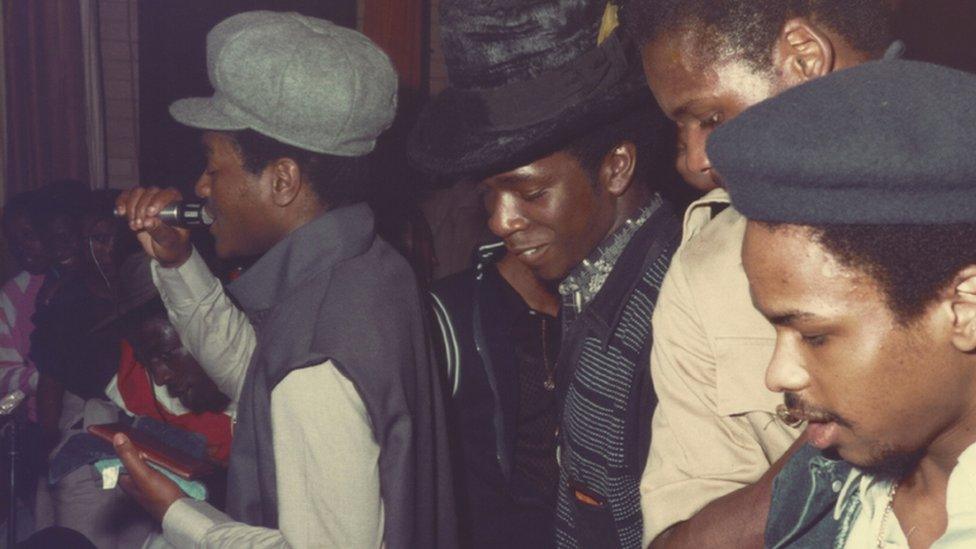

Mr Masouri says: "On Sir Coxsone, you had Daddy Freddy, you had Levi Roots - the Reggae Reggae Sauce man - you had Tenor Fly, you had Jah Screechy"

"With Saxon, you had Philip Levy, you had Maxi Priest, you had Smiley Culture, Asher Senator, Tippa Irie, Daddy Colonel.

Irie says: "What we did as MCs on Saxon revolutionised the music.

"It was Peter King who created that fast style of talking, which shifted the game from Jamaica to us because DJs like Yellowman, General Trees and Peter Metro started to follow our style after that.

"We were the first ones to write lyrics that filled up rhythms from start to finish and to tell stories in our own voices, instead of using patois.

"We could make a lyric out of anything, and we were all Cockney translators in a sense, because we were talking about what was going on around us, and what we were experiencing in our everyday lives at that time."

Saxon Crew included British reggae artists such as Maxi Priest, Smiley Culture and Tippa Irie

Mr Masouri says: "All over London, you had sound systems with people on the mic who began making records in the 80s - especially once the music became digital.

"There was a real explosion of talent at that time."

The scene was fuelled by live recordings of dancehall session distributed on tape cassettes, but they were not widely available.

"You had to know somebody or go to certain little outlets to buy them," Mr Masouri says.

Alpha & Omega at the St Paul's Carnival, in Bristol, in 1991

But, on a 90-minute cassette, listeners could hear established names on the mic, plus new artists, which helped them identify with one sound system or another.

Mr Masouri says: "If you heard a Saxon tape, and you heard a very young Maxi Priest, for example, and he caught your ear, then you would follow his career, buy his records when they came out - and it promoted that feeling of support and identification with certain sound systems, a bit like following a football team."

While for many years sound systems struggled to find venues and operated underground, Mr Masouri says recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in reggae culture.

"Thanks to the internet, the music's never been so accessible, and more and more people have taken an interest in it," he says.

"That's what's fuelling all of these books, films exhibitions and documentaries.

"I'm seeing the veterans finally get the recognition they deserve.

"Their music's being heard, their classic recordings are being heard, their history is being documented.

"In their twilight years, they're receiving some recognition for what they've done - because they did hold communities together, and I credit those sound system owners, like Lloyd Coxsone, with keeping a lot of young people out of trouble and off the street.

"They gave them a sense of purpose and a sense of belonging that they wouldn't necessarily have got otherwise."

Sound System London is at the Tabernacle until Sunday, 17 January. The exhibition series culminates with a symposium at Goldsmiths College, south-east London, on Saturday, 16 January.