Douglas Slocombe, Ealing comedies and Indiana Jones cinematographer, dies

- Published

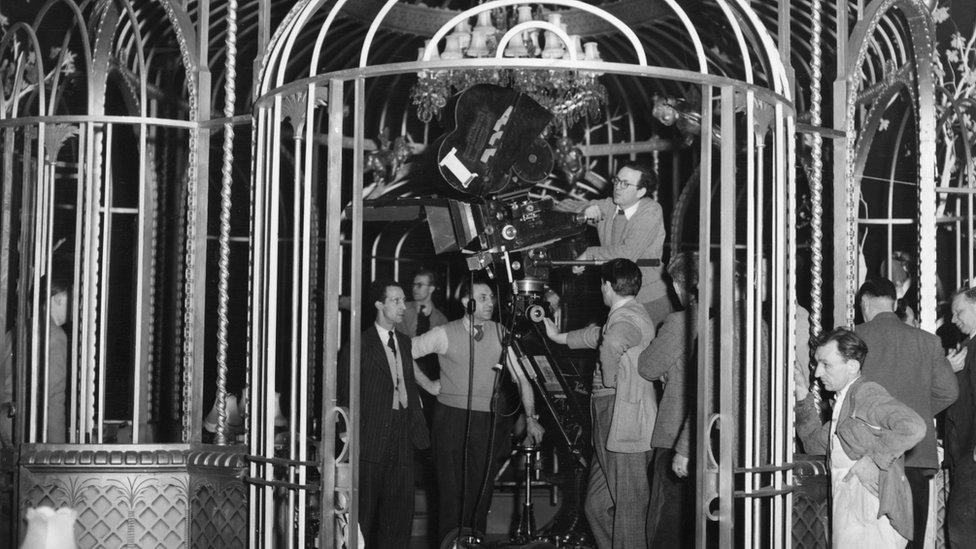

Douglas Slocombe setting up his camera on the Ealing Studios film Cage of Gold in 1950

British cinematographer Douglas Slocombe has died at the age of 103, his family has said.

Slocombe shot 80 films, from classic Ealing comedies such as The Lavender Hill Mob and Kind Hearts and Coronets, to three Indiana Jones adventures.

In 1939 he filmed some of the earliest fighting of World War Two in Poland.

Indiana Jones director Steven Spielberg said Slocombe - who won Baftas for the Great Gatsby, The Servant, and Julia - "loved the action of filmmaking".

He said the cinematographer was "a great collaborator and a beautiful human being".

"Dougie Slocombe was facile, enthusiastic, and loved the action of filmmaking. Harrison Ford was Indiana Jones in front of the camera, but with his whip-smart crew, Dougie was my behind the scenes hero for the first three Indy movies," Spielberg added.

Oscar nods

Slocombe other work included The Italian Job and Jesus Christ Superstar.

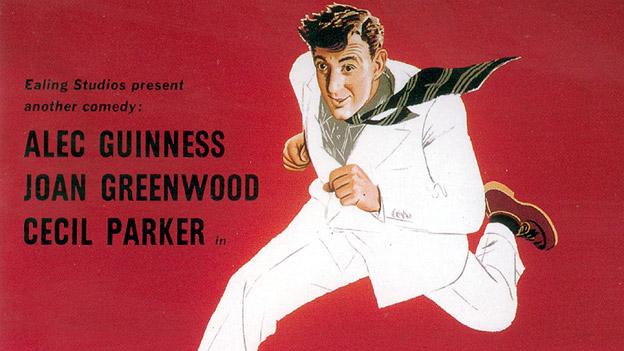

Among his own favourites was Kind Hearts and Coronets, the Ealing Studios classic of 1949, starring Alec Guinness and Joan Greenwood.

A decade earlier, as a young newsreel cameraman, London-born Slocombe had shot parts of the Nazi invasion of Poland.

The quality of that footage, which was used in the documentary Lights Out in Europe, persuaded Ealing to employ him.

Steven Spielberg chose Slocombe, then nearing 70, to shoot Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark and then two further Indiana Jones films in the 1980s.

Slocombe was nominated for an Oscar on three occasions, including for Raiders, and was given a lifetime achievement award by the British Society of Cinematographers in 1996. He was made an OBE in the New Year Honours list in 2008 for services to the film industry.

'Amiability and intelligence'

by Vincent Dowd, BBC World Service

With Dougie Slocombe's passing at 103 we've lost a link to several eras of Britain's cinematic history. His typically humane account of how as a news cameraman he escaped from wartime Poland by horse and trap and then by train would make a film in itself. He became, as he said, 'last man standing' of the great craftsmen who helped Michael Balcon turn Ealing Studios into a force to be reckoned with. Of the films he shot there he most loved the dark humour of Kind Hearts and Coronets - but he told me he was also proud of how Hue and Cry (1947) found black and white beauty in bombed-out London post-war. When Ealing closed, he went on to an extraordinary array of 1960s and 70s films: from The Servant (again, London in gorgeous monochrome) to the explosively colourful Jesus Christ Superstar in 1973.

Four years later, Steven Spielberg drafted him in to film scenes for Close Encounters of the Third Kind: they got on so well that he asked Dougie to be cinematographer on the first of three Indiana Jones movies. Dougie was already 70 when he started the job. I didn't know him until he was 100 and almost blind, but in the long conversations I had with him, his memory remained pin-sharp. The amiability and intelligence which helped make him one of the world's great cameramen were still there. His energy amazed. When he was 102, I telephoned to ask if I could come round the next day to interview him about an aspect of the Ealing years. Dougie said he'd be delighted. But it would have to be in the morning because in the afternoon he was booked in to record a five-hour TV interview - in French.

His other films included Whisky Galore, The Man in the White Suit, Rollerball and Never Say Never Again.

Speaking to the BBC last year, Slocombe recalled working under the Ealing Studio mogul, Sir Michael Balcon, as well as filming on location in a city still scarred by bomb damage.

"I think I'm the last man standing," he said. "All the major technicians and the producers and directors are gone - and that famous repertory company of actors and actresses."

Slocombe's daughter said he died in hospital in London.

- Published11 February 2014

- Published30 August 2015