Opera's radical pharaoh returns to ENO

- Published

A new production of Philip Glass's opera about the ancient Egyptian pharaoh, Akhnaten, is being staged at English National Opera. Based on the life of an insular but singled-minded leader, who introduced what was arguably the first monotheistic religion, it also features a conflict in Syria and a counter-revolution in Egypt. An opera which asks questions of performers and audiences alike, its themes continue to resonate with current world events.

"Akhnaten created this whole other culture based around the sun," the opera's director, Phelim McDermott, explains during a break in rehearsals.

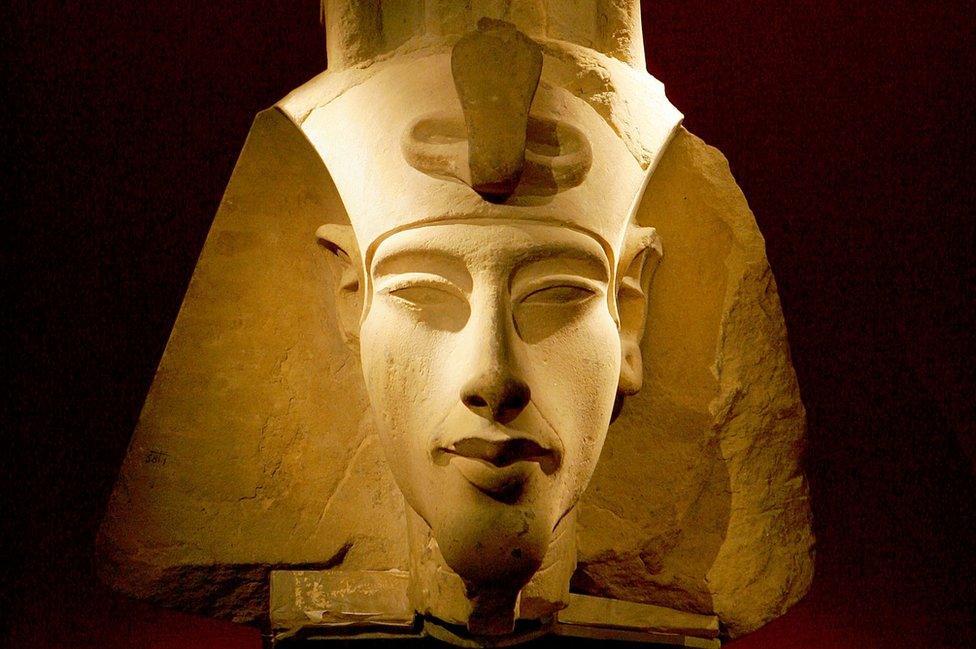

"On a certain level it was the first ecological kind of religion, and the fact that he put himself at the centre of this thing and his relationship to the sun makes him a very radical figure," he says of the 14th Century BC pharaoh, who ruled for 17 years, and was father to the famous Tutankhamun.

Akhnaten is the third instalment of Glass's trilogy of operas about great historical figures which includes Einstein on the Beach, and Satyagraha, which is about Mahatma Gandhi.

McDermott has previously worked with ENO on productions of Satyagraha, and another Glass opera, The Perfect American, based on the life of Walt Disney.

"Although the sun was a part of the religion before that," McDermott continues, "it was part of a multi-God world. So it's a transition from all these different extraordinary gods we know from Egyptian hieroglyphics.

"And it is extraordinary how he changed the culture in terms of what it looked like visually. So for instance the statues of himself and his own family and himself - very different from what we know of the archetypal Egyptian iconography.

Face of the pharaoh - Akhnaten introduced religious reforms and built a new city

Akhnaten built a new city dedicated to Aten, the Sun-God, and so as a figure in ancient Egyptian history "he's a very potent person to write an opera about", he says.

McDermott and ENO will both be hoping that potency will translate into healthy sales at the box office.

Previous Philip Glass operas at ENO have been well received, and the company says Satyagraha has been its most popular contemporary work.

This incarnation of Akhnaten is the first fully staged UK production of the opera since 1987, but it comes at a time when the Gods are not smiling kindly on ENO.

Its Arts Council funding was cut by £4.8m in 2014, and its senior management is emerging from a bruising wrangle at the top of the organisation that has left it without an artistic director since the end of the 2015 season.

And in a crucial phase of rehearsals for Akhnaten, a dispute with the ENO chorus over pay and jobs has tilted into crisis, with the company's choir announcing they will refuse to sing in the first act of the final performance of Akhnaten.

All of which adds to the pressure for McDermott to create opera gold for ENO out of a minimalist piece, with slowly evolving motifs which unfold over long periods of time.

But speaking ahead of the chorus's decision to go on strike, the director was relaxed about the challenges of producing the opera during an industrial dispute. "This is my third Glass piece," he says, "so I've been on a journey with the company.

"I've been on a journey" - Akhnaten is McDermott's third Glass opera for ENO

"The chorus, when we first did Satyagraha (in 2007), weirdly were going through a period of redundancies. And I was asking them to do a Philip Glass piece in which they were singing in ancient Sanskrit.

"We did it (Satyagraha) three times at ENO, and each time we did it, it got stronger and more confident. We realised we'd created quite a unique piece there, a very strong piece".

Back in the present, the dispute behind the scenes provides a backdrop for an on-stage drama of grand proportions.

Akhnaten's religious reforms were reversed after he died

Incorporating texts drawn from ancient hymns, prayers and inscriptions sung in their original languages, Glass's opera depicts the ancient ruler ignoring pleas for help from his vassals in Syria, who are under attack from enemies of the kingdom, before being overthrown and killed in a popular uprising led by priests of the old religious order.

In fact, it is not clear exactly how Akhnaten died. What is certain is that after his death, the pharaoh's religious reforms were reversed, and the city he built was abandoned - later rulers would plunder it for materials for their own tombs and monuments.

"There is this story of a kind of closed inner community that he created," says McDermott, "this quite inward looking world he creates at his own court - and him not listening to what's going on, the kingdom being attacked at various points.

"We see his kingdom falling because things are decided by the outer community that will go back to how things were - the re-establishment of the old order.

"That religion was incredibly complicated," he continues "and when you look at it, it's almost like something from a sci-fi movie. Passing into the underworld didn't mean going somewhere else, it meant being in a parallel universe.

"So those figures that have passed into this other life haven't gone away - they are still present for the ancient Egyptians."

Akhnaten, he says, was "the person who was at the centre of this epic world - a real person".

Ancient bones - a skull believed to be that of Akhnaten

The task of making Akhnaten live again on stage falls to American counter-tenor, Anthony Roth Costanzo.

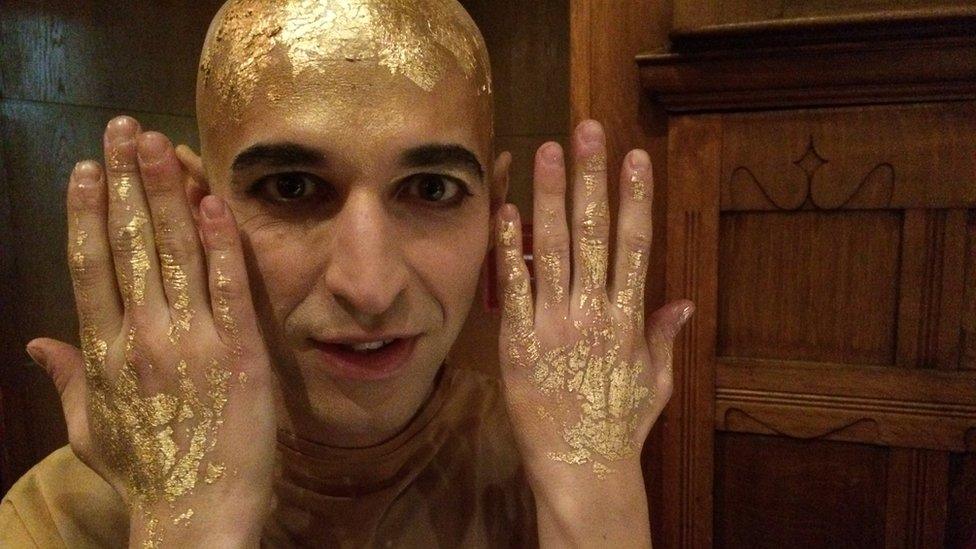

The American singer says portraying the pharaoh in a convincing way requires "full-bodied devotion" - an idea he has put into practice literally.

Beyond learning the music - "making sure it's in your brain, in your body, your muscle memory" - he has undergone a physical transformation too, shaving his head, removing body hair, and, conscious that he will appear on stage completely nude, a rigorous workout programme.

"We actually waxed every inch of my body that they could find any hair - so it was very painful. And shaving my head was a big decision," he says.

"But what really convinced me more than the look of it, is that there is an aspect of the psychology of shaving your head - I'm on stage for three hours, singing very minimal music with very little text and narrative to latch on to as a performer, so what can I do to tell the story?

"Being in this headspace - literally - it helps convey a narrative."

Sun-worshipper - counter-tenor Anthony Roth Costanzo in full make-up as Akhnaten

Costanzo describes singing the part as "like running a marathon", requiring endurance and supreme concentration. "It takes more focus than even a Handel opera, because if you take one wrong step in Philip Glass you could find yourself 18 bars off very quickly."

He has been encouraged by McDermott to "radiate forth the opera" from the stage.

"You think about that and feel that the whole time you can really hold the attention of the public," says Costanzo. "But it takes so much from you. It takes so much to just hold that and make the air feel meaningful."

McDermott used puppetry in his ENO staging of Satyagraha, and animation for The Perfect American. For Akhnaten, he has turned to ritual and movement, which he describes as an "exciting element" using "choreography and juggling in hypnotic unfolding patterns that are kind of revelatory", which he hopes will take both his singers and his audience into a different state of mind.

"There's something very exciting about the vocabulary of this one," says McDermott. "Anyone who's done a Philip Glass piece knows you can't not slow down - you can't make people move on stage as fast or as naturalistically say, as they would in a different kind of opera.

"When he (Glass) first did his operas, I don't think he knew that on a certain level he was also inventing a particular performance style.

"You have to take the performers into another sensory level where they're almost performing on stage whilst meditating. If they manage to do that well it leads the audience into another zone.

"And of course there will always be people who don't take the invitation - but people who do go with it go into that other zone and actually the time changes, and an hour and a quarter goes incredibly quickly.

"What's unique about opera is it's this live experience where performers go into these other states."

Philip Glass's music has been criticised as soporific, a cop-out which avoids deeper meaning. But McDermott dismisses that view.

"I would say it's exactly the opposite - it has deeper states that you've got to open yourself to, more vulnerable states.

"So although some people say 'oh, it's bubble bath, it is avoiding', I would say you can't avoid these deeper levels and Philip's music looks at these levels of reality that can only be discussed by opera."

ENO's production of Philip Glass's Akhnaten opens on 4 March 2016 at the Coliseum, London.