Why the ENO needs a Fergie

- Published

If you want results, it helps to have experience. Just ask Sir Alex Ferguson

You will probably be aware that the English National Opera is in trouble. Again.

Frankly, following its fortunes is like supporting the England football team: a woeful affair kept tantalisingly alive with occasional moments of brilliance and the promise of a better future.

Neither outfit has managed to live up to their '60s heyday, despite big money investment and a revolving door of "I can fix it" managers boasting state-of-the-art tactics.

They are both overshadowed by seemingly superior neighbours. The ENO has the well-heeled, well-supported Royal Opera House to contend with, while the footy lot have the Germans.

There are similarities. But I'm not sure, even in the madcap world of football administration, a national manager who has never been a boss would be appointed. I just don't think they'd give the top job to someone who has never been in charge of a team, any team - be it a rugby squad or a bar billiards partnership.

It wouldn't happen, would it? Well, not at the FA perhaps. But it has at the ENO.

Its board has hired a young, inexperienced CEO who has never run a company of any sort, who has never had a full-time job in the arts, and has no track record in opera.

That might strike you as a bit risky at the best of times, but given the ENO's dire situation - trying to cope with a £5m cut to its annual budget by Arts Council England - it could appear reckless.

And that's before you take into account that the post was not advertised, nor were any alternative candidates interviewed.

That's not the CEO's fault. But isn't it like asking someone who has never driven a motor (but has passed the theory test with flying colours) to take control of a racing car with a dodgy clutch? It could work out, but you're not exactly stacking the odds in your favour.

That's not to say that Cressida Pollock, the CEO in question who was hired in March 2015, isn't up to the job. I found her personable and passionate when we met, and I wish her and the company well.

Singers at English National Opera have voted to go on strike

But if I were a member of the 44-strong chorus that she intends to reduce to 40 while cutting the income of those that remain, I might feel a little uneasy about her lack of experience. Their professional lives are in her hands, and she is giving them a squeeze. And they don't like it. Industrial action is imminent.

Maybe they are wrong to strike. Maybe Ms Pollock has made the correct decision in the circumstances. Maybe she is right when saying the ENO is operating "a fundamentally flawed business model". The "decades of trying to make it work", along with the £33m of bail-out money it's received from Arts Council England over the past 20 years is proof of that.

Maybe it is - as she says - an organisation "falling down the stairs slowly". Maybe. But then, maybe it is not.

Maybe it's much worse than she and her board think, and a more rapid, terminal tumble would be better and kinder to all. Maybe the very idea of an English national opera is fatally flawed. Could it be that the money needed to make sense of the concept of a "people's opera company" is too great in our austerity times? Maybe Ms Pollock should be more radical and not seek to trim the head-count and salaries, but cut the lot - herself included.

Or - maybe - the ENO should take on the relatively low-cost model of the National Theatre of Scotland, which operates without a physical base and all the associated costs. But then that wouldn't really an English National Opera; it'd be more like a production company that specialises in opera. And that isn't the same.

Professional opera, like pro soccer, is a team game in which a group of talented players have a coach (conductor) whose job it is to elicit from them a top-notch performance. Generally speaking, the better the coach, the better the team, and the better the performance. Which is why there was an all-conquering Manchester United under Fergie, and a pale imitation (largely the same players) without him.

Mark Wigglesworth became the ENO's musical director last year

I can't imagine the sensitive Mark Wigglesworth - the current musical director of the ENO - gives either his orchestra or chorus the hairdryer treatment, but they certainly up their game for him. (Check out the reviews for the ENO's production of The Magic Flute which he conducted.)

He works with them day in, day out. Their artistic achievement is a collaborative effort brought about by earned trust and a deep knowledge of the company's canon. You can't simply hire a bunch of strangers and expect them to hit the same high notes, as consecutive managers of the England football team have discovered.

If there is to be an English National Opera at all, there has to be a core team of musicians and singers. That is the stance of Ms Pollock and her board. The question is, how many do you need?

The potential problem with the proposed solution, according to Mr Wigglesworth's recent article in The Guardian, external, is that cutting the chorus further (it has already been significantly reduced over the past decade) risks "compromising" the whole operation. It would, he says, "damage irreparably" the company's output.

It is possible the respected conductor is merely sabre-rattling on behalf of the musicians, but it's reasonable to argue that if you offer less favourable pay and conditions, the outcome is likely to be that the best singers go and find another job and leave the less gifted behind. Those that remain might then struggle to reach the same standards without their more talented teammates showing them the way. A lose lose looms.

But what choice do they have? After the recently departed artistic regime led by John Berry - who put on some cracking shows but lost a large chunk of the core audience, the sympathies of ACE and the confidence of the board - it has become harder for the management to trust the arty types to fix the problems. But opera is a content business, and if those in charge of content can put you in the mire, they are also, probably, the only ones who can drag you out.

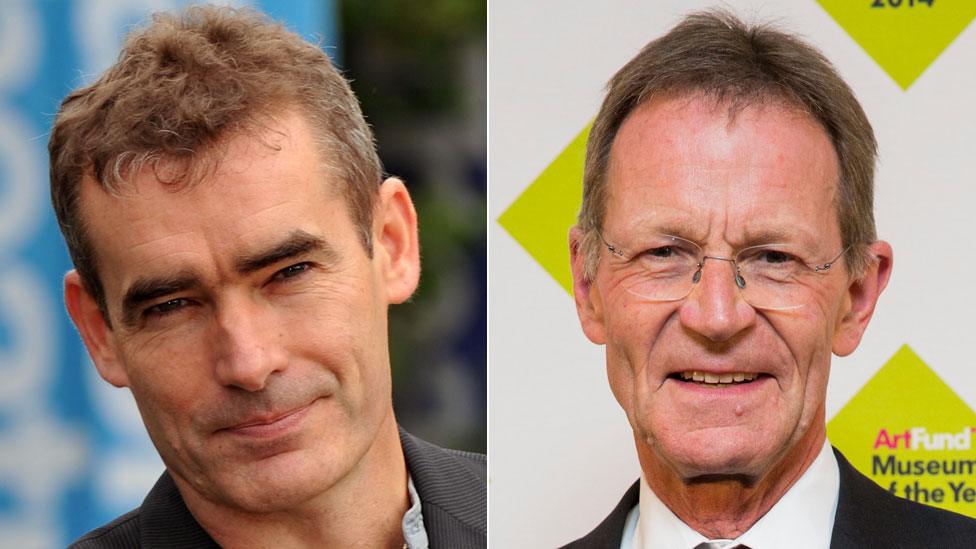

Rufus Norris (l) and Sir Nicholas Serota head up the National Theatre and Tate respectively

Ms Pollock and the board might have to take a deep breath and believe in the new artistic director enough to give her or him their head. John Berry reported to the Chair, the new artistic director reports to Ms Pollock. Does Rufus Norris at the National Theatre or Nicholas Serota at the Tate report to a CEO? I don't think so.

If the ENO had an artistic director in place (they hope to fill the long-vacant post by April), would he or she have agreed that cutting talent was the only way forward? Would other options have been explored? Would a strategy of putting on more shows for less have been explored? Who knows?

The fact is those decisions rest with Ms Pollock and her board. I only hope they remember, while they try and figure out the future, that opera is ultimately all about listening to the musicians.