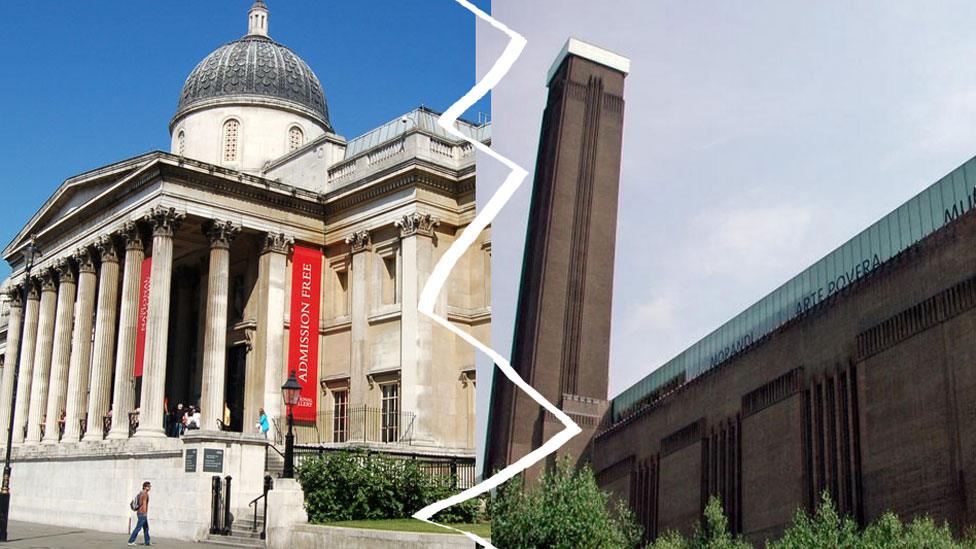

National Gallery / Tate divide

- Published

There is a fundamental flaw in an historic agreement between the National Gallery and the Tate. The two institutions settled on the idea of having a dividing line about twenty years ago, and came up with the idea that 1900 would be a suitable date at which to separate their collections and displays. It deal was precipitated by the then-imminent arrival of Tate Modern.

It was agreed by Messrs McGregor and Serota that the National Gallery would show international art up until 1900, while Tate Modern would present work produced from that date. Simple.

In fact, too simple, 1900 might be meaningful in terms of calendar dates, but it has absolutely no relevance to art history. Art didn't stop on the 31st December 1899 and then restart afresh and anew first thing the next day. No great art movement stopped at the end of the 19th Century, and none of note started in 1900. It is, frankly, a facile date to choose.

And now that agreement is at risk. Gabriele Finaldi, who started as director of the National Gallery six months ago, has called it into question, hinting he wants to expand his remit well into the 20th Century.

Art historians would happily write and talk at length about the date you could and should divide the collections of the two national institutions, but it'd always be open to challenge and debate. And that's because all art connects. As Cezanne once said of his own avant-garde efforts: "I am simply adding another link to the chain". Art is ever evolving, which is a fact the two institutions and their collections need to reflect.

Cezanne's link in the chain is a case in point. He was predominantly a late-19th Century artist, although he died - working right up until the end - in 1906. He absolutely has to be in the National Gallery's collection, which is why Tate - as part of the agreement - has loaned its Cezanne to the good burghers of Trafalgar Square.

But, you can't seriously tell the story of Cubism - a 20th Century art movement that falls within Tate's remit - without acknowledging the debt it owes to Cezanne's pioneering work. Matisse and Picasso - two modern masters in the Tate's canon - described him as "the father of us all".

The same applies to Expressionism, which has roots in Van Gogh's 19th Century paintings (National Gallery), but is shown in all its anxious glory in Tate's displays of German and American Expressionism. The 1900 line is blurred, to say the very least.

It is a false wall: an open border that the two institutions have happily crossed in the recent past. Tate had its blockbuster Gauguin exhibition, although he is a 19th Century artist; the National Gallery has dabbled in the contemporary.

The reasonable way forward is for each institution to tell the stories it wishes to tell within the context of their collections. For that is what really separates the two: they are addressing the same subject in very different ways. The National Gallery has an art historical perspective, the Tate's is staunchly contemporary.

There are other differences, too. That National Gallery, for instance, only collects and displays paintings: it is into two-dimensional art. The Tate, on the other hand, has galleries (and warehouses) full of sculptures, installations and sound pieces.

That the two institutions cross over is inevitable, and - in my opinion - to be encouraged. There are many ways to look at art, and we, the public, no more want to look at the subject from a single perspective than did Picasso (or Cezanne, for that matter).

If the National Gallery thinks displaying a painting by the contemporary artist Peter Doig next to one by El Greco will illuminate both in an interesting way, it should be allowed to do so. Similarly, if the Tate Modern curators are itching to pair Pierro della Francesca with David Hockney, why not let them?

In New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) co-exist with both presenting modern and contemporary art. The get along well enough, but can find themselves competing for pictures at auction or in the form of gifts, which can be awkward. This is the area of activity where some clarity can be helpful.

The need for some sort of dividing line is required when it comes to collecting. It is not in the interests of the British public to see two of its major public art institutions competing and bidding up the price of a painting at auction. That'd be daft. If they both want to buy a Picasso circa 1901, they should discuss it beforehand and come to an agreement that one or other institution will try and secure the work for the nation. They could even share the costs and the picture.

And if they can't agree? Well, I would then recommend they ask a grown-up to decide on their behalf.