Conceptual art: What’s the big idea?

- Published

Pablo Bronstein makes 'playful investigations into Rubenesque baroque with a dollop of contemporary irony'

I'm down at Tate Britain and chatting to an old friend and half looking at a performance art thing happening in front of us when I realise we are the most attentive inattentive art-watchers at the early evening private view.

So, we weren't exactly concentrating on the choreographic goings-on central to Pablo Bronstein's newly unveiled performance installation, but at least we were giving it a respectful this-is-the-reason-for-all-the-free-hospitality glance.

The other 400-odd attendees appeared to feel no such compunction for half-hearted pretence, and chose instead to shamelessly ignore Bronstein's creative endeavour - although not the artist himself for whom they had all the time in the world.

Bronstein is a favourite among thrusting young curators looking for the next big thing. His shtick is to make playful investigations into Rubenesque baroque with a dollop of contemporary irony thrown into the mix.

Drawings and performance are his preferred media, as is the case with this installation in Tate Britain's Duveen's Galleries.

Three dancers dressed in black leggings and bright red tops adorned with big white-balled necklaces strike poses while moving gracefully along strips of white tape that have been temporarily stuck to the floor.

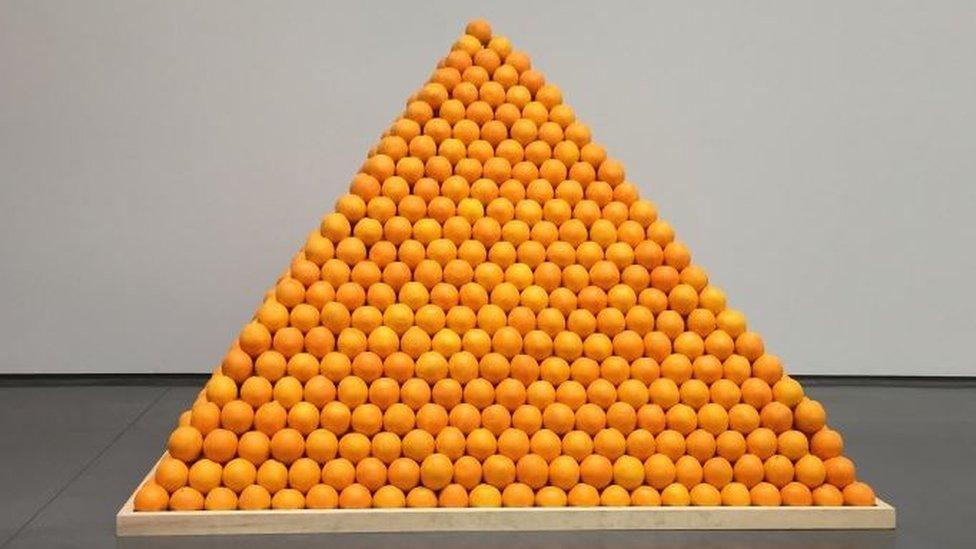

The Tate encourages you to take a piece of the fruit from Roelof Louw's work

They are framed by two huge pieces of scenery at either end of the vast hall, onto which the artist has drawn a satirical trompe l'oeil depicting the museum's neo-classical facade. There's some occasional piped music too.

There's lots of art historical references, from Raphael-type sprezzatura posing to Bruce Nauman's Pythonesque square-bashing. None of which impressed an earnest critic-cum-curator passing us en route to the drinks waiter, who dismissed the work by saying: "Pablo's been repeating himself for years."

"So have you darling," my friend said under his breath. And then we gave it more attention and agreed Bronstein's efforts would please the new director of Tate Britain who likes "that sort of thing".

As do I, to be honest. And this one is ok - not his finest work, but enough to liven up a difficult space. It's full of ideas like a boxer is full of punches, but it's landing them that counts, and there's too many glancing blows to make the piece a knockout.

Unlike the Conceptual Art in Britain show in the adjoining galleries, which the critics have slated for being pretentious and boring.

I went to take a look. The vibe was different in there. People were actually looking at the art, for starters. And there was a palpable feeling of intensity.

A pyramid of oranges by Roelof Louw called Soul City (1967) is the first thing you see. I was (you are) invited to take one (from the top is better, those below are bruised) and eat it later ('not in the gallery please sir').

I'm guessing we're into ideas about art, decay and consumption here, which given the stories of Damien Hirst's disintegrating sharks and the greedy commodification of art this century, strikes me as rather prescient.

The Conceptual Art in Britain exhibition is 'the opposite of what we expect from art'

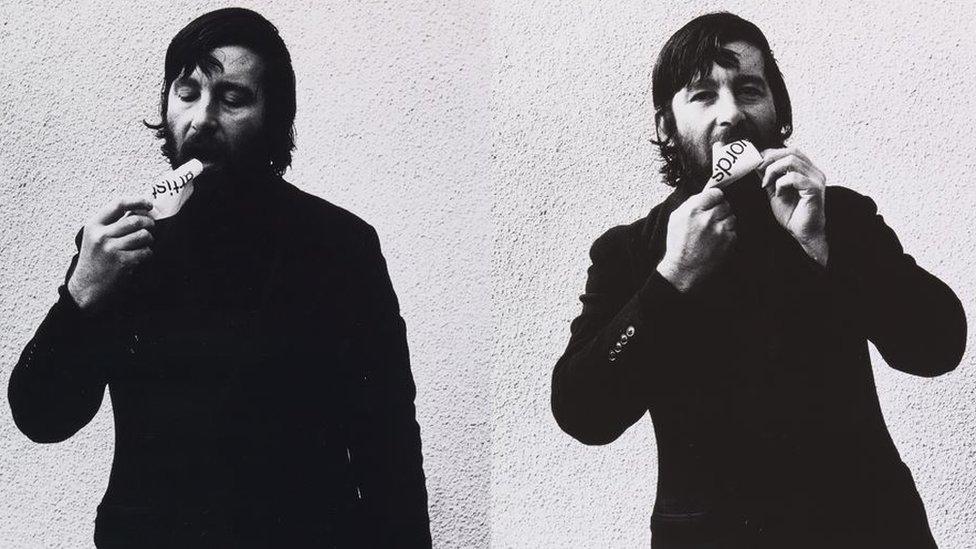

All the work in the show dates back to the late 60s and early 70s, most is either black and white or grey, and all of it is very "serious".

I'm picturing male artists with beards who tinker with cars in their spare time, and female counterparts who think laughing is for imbeciles. That might be way off beam, but that's how the show feels. And I think that's what the critics don't like, but I'm lapping it up.

Most of the exhibits are so intellectually convoluted in conception, and so utterly stark in realisation that you need to read an essay (provided as wall captions next to the artworks) on each one before having a clue what you're looking at or what for.

It's the opposite of what we expect from art. Normally, we look at a label for a date and artist name, and then find out what he or she wants to express and explore by studying the painting or sculpture or performance.

In this show you do it the other way around. The starting point is the image; from which you work backwards through the text to discover what on earth it is the artist is getting at.

You could argue that's what books are for and not gallery walls, but I disagree. You need these ascetic works set in the context of a public gallery, which - as Bronstein's creation a few feet away demonstrates - have become places for colourful entertainments and snazzy cafes.

Which is fine, by they way, I have no problem with that - but it makes the professorial seriousness of the 60s and 70s conceptual work all the more potent.

The Conceptual Art in Britain show is so full of ideas, almost all of which the artists land, that you come out with your head spinning and wondering where to go in the contemporary realm to find an equally considered, sincere investigation about the meaning of art.

One place might be the Chisenhale Gallery in east London, except it is closed for the next five weeks. Not for refurbishment, or an art installation, but by decree of Maria Eichhorn, a Berlin-based artist who - for her solo show there - has decided to shut the gallery and insist the gallery staff take the time off.

That's right, we're talking "Arts Council Funded Gallery Pays People Not To Work!" type thing. But it's smart don't you think? It poses lots of questions about how we work, what work is, and when or if we can stop working.

How many Chisenhale staff were at Tate Britain on Monday, for instance? And if any were there chugging back the wine, was that in work capacity or just for fun, or both. There's nothing to see at the Chisenhale, but like Tate's conceptual art show, plenty to think about.

Pablo Bronstein's Historical Dances in an Antique Setting can be seen until 9 October.

Conceptual Art in Britain is at Tate Britain until 29 August.

- Published25 April 2016