Turner Prize: Art not gibberish, please

- Published

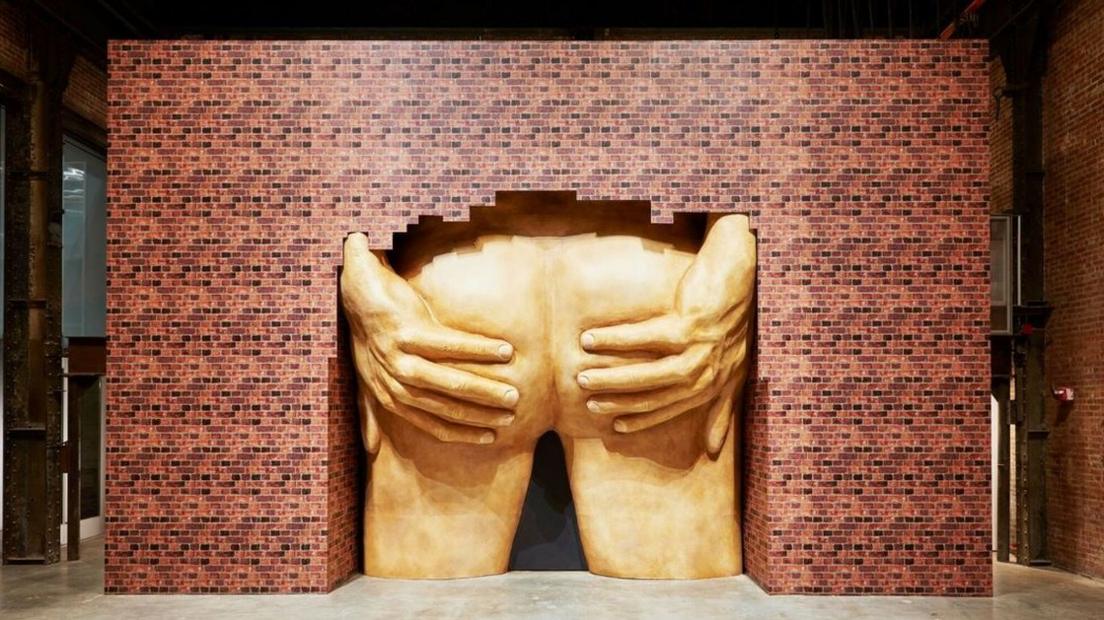

Anthea Hamilton explores desire, fetish and pop culture

To start, a moan: why do the Turner Prize curators write such unintelligible gibberish about the artists shortlisted for the prize?

Where do they go to learn to produce these texts laden with pseudo-academic speak? Does their dense, mangled prose reflect a lack of confidence in the artists whose status and work - the curators' might think - needs to be elevated by arcane, pompous language?

Or, perhaps, it is insecurity about their own place in the "snobby" artworld (as Laurie Anderson described it to me) that leads them to write such nonsense?

To be clear: The purpose of the Turner Prize is to provoke a conversation about contemporary art among the public. The stated role of the Tate is to "increase knowledge, understanding and appreciation of art".

Both objectives are undermined and poorly served by the incomprehensible "artspeak" used by the institution's curators. It is not clever and it is very off-putting.

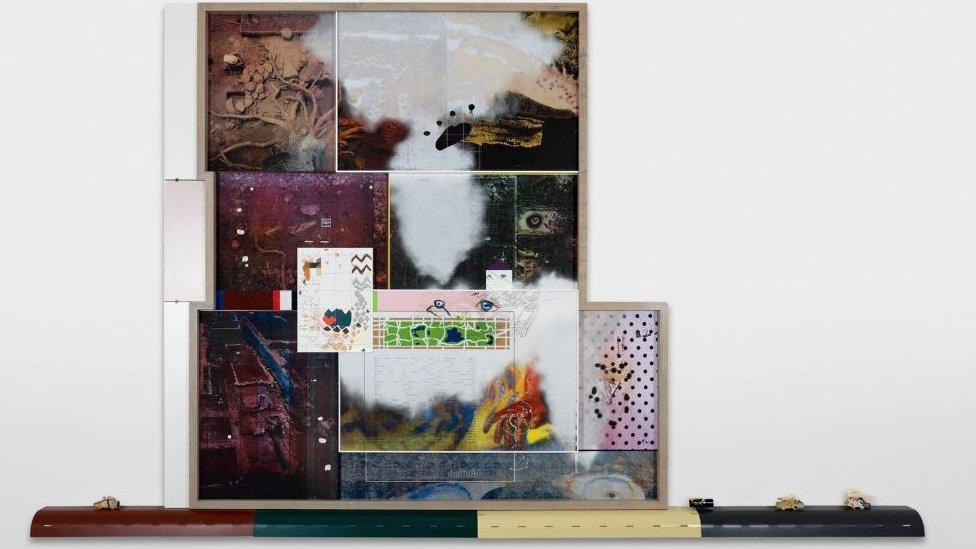

Helen Marten's 'objects read almost as hieroglyphics, a visual system of communication that is expressive yet rooted in logic,' says the Tate

Here, by way of example, is an explanation of Helen Marten's work: "Whilst their complex references might not be made immediately explicit to the viewer there is something alchemic in the way the materials collide, and ideas are often communicated through the obstinate wilfulness of the finished form.

"Marten's objects read almost as hieroglyphics, a visual system of communication that is expressive yet rooted in logic, which makes rational the combination of a pickle with an electrical circuit, or a pillar drill alongside a bowl of fish skins."

You get the point, I won't go on - and nor should the curators who wrote the texts, until they've been on a plain-speaking course or locked in a room with a collection of books by masters of writing about art such as Ruskin, Gombrich, Hughes and - for good measure - Bridget Riley.

Okay, onto the shortlist of four artists. All work in variety of media, but for simplicity's sake, I think it's fair to say we're talking about three sculptors and a photographer. They are mostly all based in London.

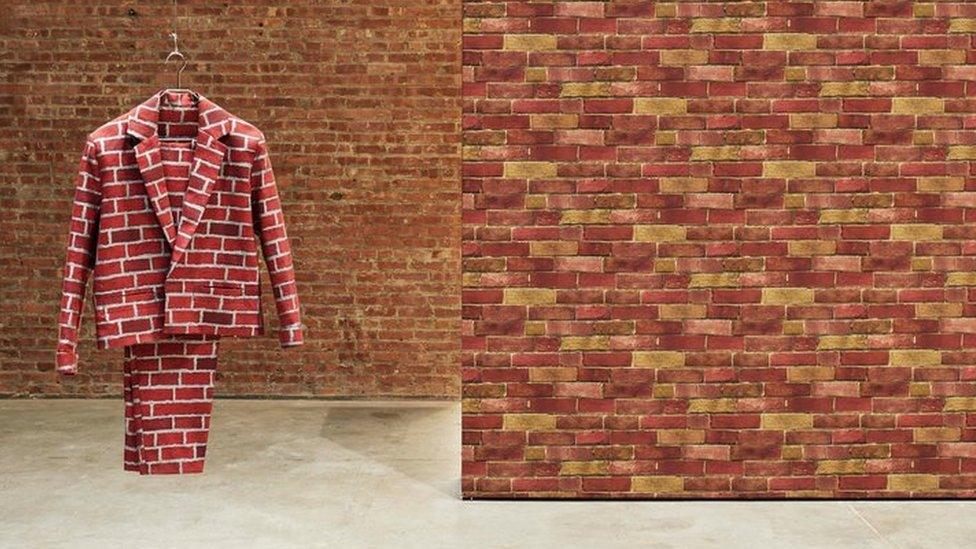

Josephine Pryde's interest is photography in the main but a train to travel around viewing it is a bonus for visitors

Michael Dean is a 38-year-old sculptor who makes pieces out of concrete and other DIY-type materials. His work tends to be rooted in his interest in language. He is the only male on the list.

Thirty-year-old Helen Marten is the youngest of the four. Collage plays a big part in her work. She has a cut-and-paste aesthetic, making sculptures out of combinations of wildly differing elements. They are designed to be awkward, to get you looking at the world afresh. She makes screen-prints, too.

Josephine Pryde is 49 and the oldest artist on the list and the one focused on photography. Although rooted mainly in London, she spends a lot of time in Berlin. Her shtick is staged photographs that mimic the slick, glossy imagery of advertising and fashion.

Michael Dean - the only male on the shortlist - likes bits of concrete and things left lying about to make his pieces

Anthea Hamilton is a 37-year-old sculptor who makes pieces and installations that explore desire, fetish and pop culture. You might say she's taken up Meret Oppenheimer's pre-war surrealist vibe via Allen Jones's Clockwork Orange sets.

It's a good list and am I am looking forward to seeing the show when it opens in September.

One thing that struck me when looking at the line-up was how all four artists seem to be more interested in modes of representation - advertising, language, film - than directly in the physical world. A reflection, maybe, on the reality of everyday life in 2016, which is more often than not mediated - and consumed - through a filter of media rather than at first hand.

- Published12 May 2016