Obituary: Richard Rogers

- Published

Richard Rogers, Baron Rogers of Riverside, helped design some of the most remarkable buildings of the past 50 years, including the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Lloyd's building in London and the Millennium Dome at Greenwich.

They were utterly original structures: exhilarating, beautiful, playful and strange, technologically innovative and visually striking.

Lord Rogers, who has died aged 88, was one of the first Britons to become a global architectural superstar - the other was his erstwhile partner, Norman Foster. He won commissions ranging from airport terminals to law courts and office buildings to housing, in countries as far afield as Taiwan, Colombia and the United States.

It was a remarkable achievement for a man who couldn't really draw, and who couldn't read until the age of 11.

Richard Rogers was born in Florence on 23 July 1933. For the rest of his life, his ideal urban space was the piazza, preferably filled with strolling citizens of all ages and classes, of the kind he remembered from his Italian childhood.

Despite his name, he was Italian. His father's family, originally from Sunderland, had emigrated from Britain around 1800. Rogers' parents brought him from Mussolini's Italy to England when he was six.

He had a rough time at boarding school. "Art was for sissies, and I was always bottom of the class," he told one interviewer. He didn't realise, he said, that he was dyslexic until his own sons were growing up.

His first sight of 1960s New York was a revelation

Nevertheless, in 1954 he won a place at the Architectural Association in London, then the most avant-garde architectural school in Britain. Initially he struggled there too. One early report read: "His designs will continue to suffer while his drawing is so bad, his method of work so chaotic and his critical judgment so inarticulate."

But then he came under the spell of Peter Smithson, a pioneering modernist who spotted his potential and encouraged him to such an extent that in 1961 he won a scholarship to Yale.

Rogers was deeply impressed when he docked in New York. "The boat arrived at dawn and I remember going on deck and being absolutely shocked and awed at the change of scale, from toy-town England to this immense steel structure of high-rise buildings. You had great canyons all the way down. I'd never seen anything like it."

Traditional techniques

At Yale, he met Norman Foster, who had studied architecture at Manchester, and the pair toured the States, sampling as much modern architecture as they could - in particular the modernist houses designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

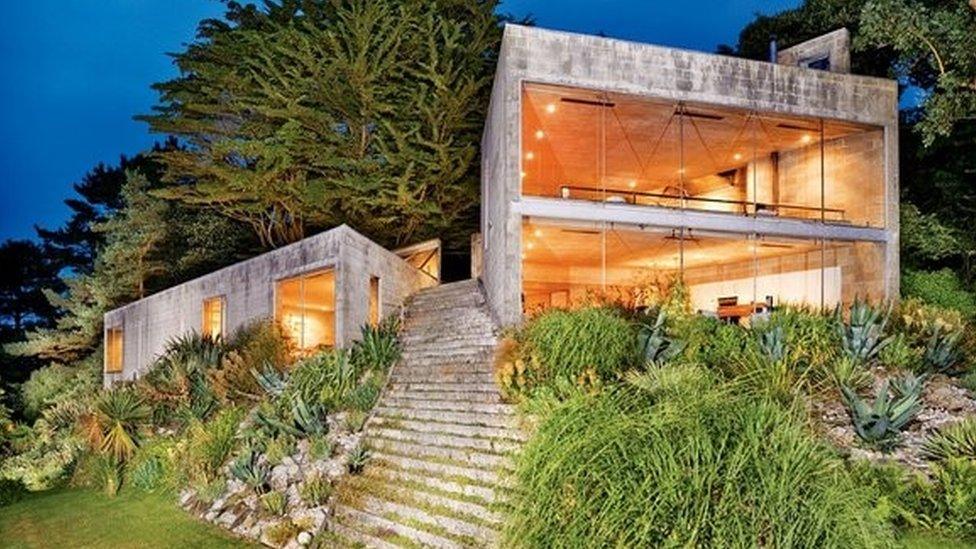

Back in England, they formed a partnership with their respective wives, Su Brumwell and Wendy Cheesman, called Team 4. They spent three years building a striking house for Brumwell's parents, Creek Vean, beside the estuary of the River Fal in Cornwall. It's now a listed building.

Creek Vean was constructed in a modern style from traditional materials

Essentially hand-crafted, it looked modern but was built (expensively) using traditional materials and techniques - a far cry from the hi-tech modernism with which both Rogers and Foster were later associated.

They also built a factory in Swindon for Reliance Controls, which was demolished in 1991, and another house in Hertfordshire which featured in an especially brutal scene in Stanley Kubrick's film A Clockwork Orange.

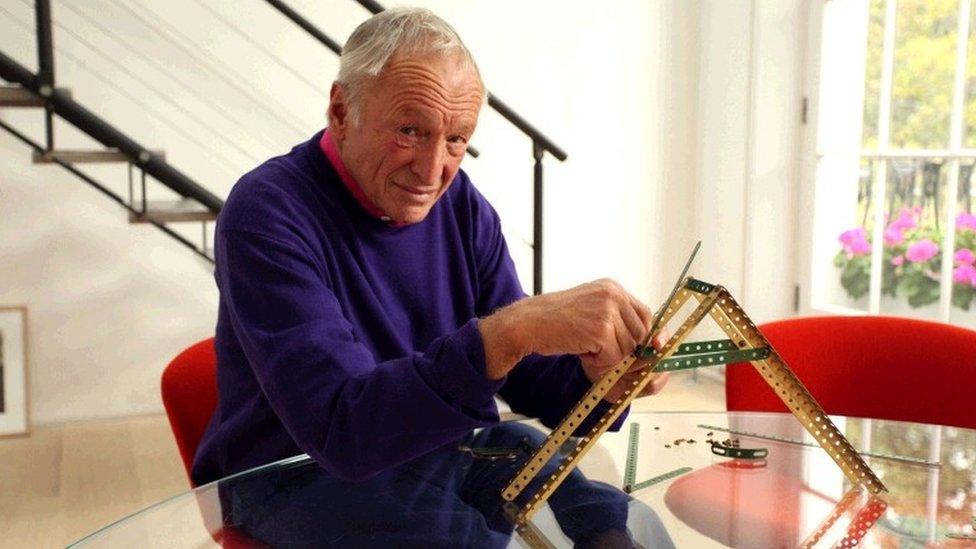

In 1967 the partnership broke up. Rogers began developing a new architectural approach, influenced by the Meccano he had played with as a boy: assembling buildings from pre-fabricated components like a kit of parts.

Astonishment

He produced a concept he called the Zip-Up House, and built a home in Wimbledon for his own parents, a single-storey yellow-painted steel frame with glass end walls and moveable partitions inside to allow the space to be reconfigured.

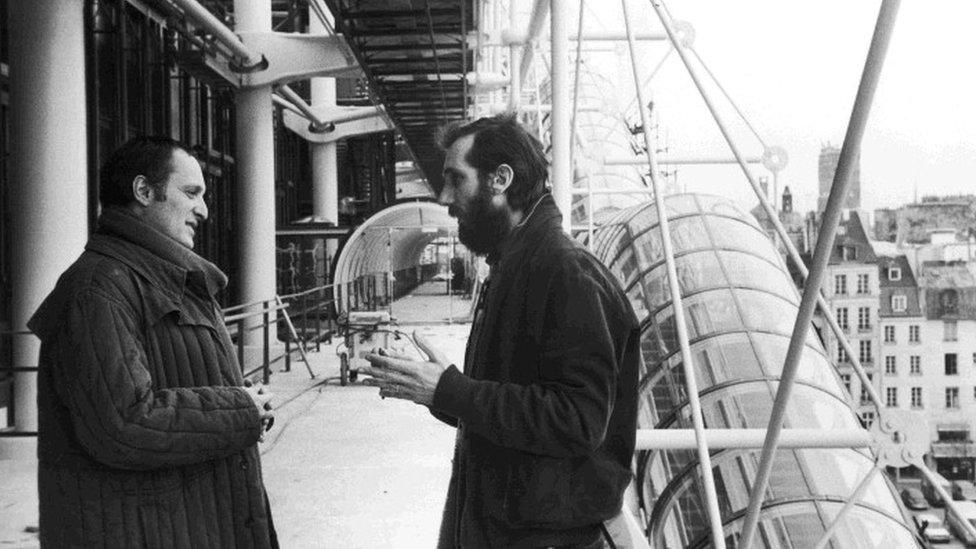

Rogers' career was in the doldrums when his then-partner Renzo Piano (later to become another international superstar) suggested they enter a competition to design a centre for contemporary arts and culture in the heart of Paris.

Rogers (l) & Renzo Piano designed the futuristic Pompidou Centre

There were 681 applicants to design the Pompidou Centre. To their astonishment, they won. The building contained elements that were later to become hallmarks of the Rogers style: a dramatic metal skeleton, bright pop-art shapes and colours, exposed ducts and services, and large clear floors allowing internal flexibility.

Equally important from Rogers' point of view, the building occupied only half the site: the rest was given over to public open space - a piazza.

Some critics hated it, likening it to an oil refinery or a space ship dropped into the centre of the city. But the public loved it, not least for the escalators carrying visitors up the side of the building in a clear plastic tube.

Extraordinary

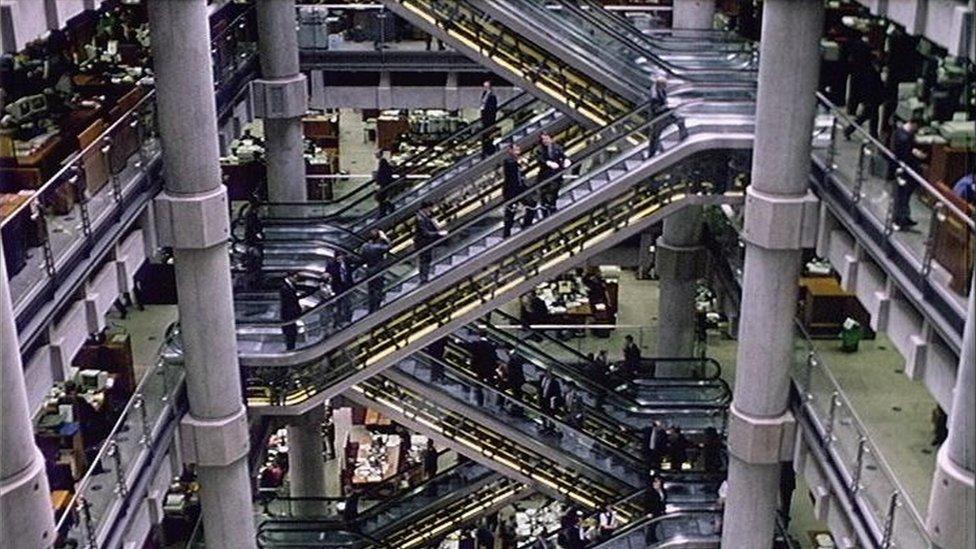

Rogers followed the Pompidou Centre with an equally striking intervention in a second historic urban centre. The Lloyd's building in the City of London, completed in 1986, is another inside-out building, a looming tower finished in polished metal. Lifts, staircases and air-conditioning ducts are on the outside.

From the roof project a series of cranes or gantries for maintenance cradles. Inside is a dramatic space: a vast atrium criss-crossed by escalators. If the Pompidou aesthetic is playful, this is deliberately awe-inspiring, almost gothic.

Not everyone was happy with the Lloyd's building, which was costly to maintain

That Rogers was able to persuade the burghers of Paris and the stuffed shirts of Lloyd's to commission such extraordinary structures says much for his powers of persuasion. In fact, neither building, conceived in an era of hi-tech optimism, wore quite as well as hoped, or performed quite as expected.

In 2000, the Pompidou Centre reopened after a three-year refurbishment that did away with many of Rogers' and Piano's ideas for the interior. By 2014, Lloyd's of London was reportedly thinking of moving - the building had become too big, but also too expensive - though it still remained at the site Rogers created at the time of his death.

Clashes

But at the time, the Lloyd's project led to a spate of commissions: a new building for the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg; a new headquarters for Channel 4 in London; the Daimler Chrysler building in Berlin's Potsdamer Platz; Terminal 5 at Heathrow (a project begun in 1989 though completed only in 2008).

Rogers became a public figure, sometimes a controversial one. A plan to redevelop a site on London's South Bank fell foul of a campaign led by the residents of Coin Street, who objected to the emphasis on hotel and office buildings. In 1984, the Coin Street Action Group purchased the land themselves.

The vast unsupported roof was a feature of Heathrow's Terminal 5

The Prince of Wales unfavourably compared a Rogers plan to redevelop Paternoster Square beside St Paul's Cathedral in London to the efforts of the Luftwaffe. It didn't go ahead. The pair clashed again in 2009 when the Prince wrote to the Emir of Qatar, who owned Chelsea Barracks, to protest at Rogers' plans for redeveloping the site.

Some of the biggest names in the world of art and architecture wrote to The Times telling the Prince to back off... but the Rogers scheme was scrapped.

In 1996, Rogers was asked to design a home for a millennium exhibition planned by the government for the Greenwich peninsula in east London. He handed the project to two colleagues, the architect Mike Davies and Ted Happold, founder of the engineering firm Buro Happold.

Prestige projects

They came up with a plan for a gigantic tent suspended from 12 angled pylons, and made of a tough and lightweight material, PTFE-coated glass-fibre fabric. The Dome was one of the lightest structures for its size ever built. Its content was hugely controversial; the building itself met with widespread approval.

For the most part, Rogers' practice focused on prestige projects for public and commercial clients - although the proportion of commercial work increased as the years went by. As well as his much admired Terminal 5 at Heathrow, with its sweeping roof enclosing a vast interior space, there was Terminal 4 at Madrid's Barajas Airport, with its undulating roof of bamboo. It won the Stirling Prize.

Madrid's Barajas Airport won him a Stirling Prize

Rogers gained a second Stirling Prize for a very different and much smaller building, a Maggie's Centre for cancer care at Charing Cross Hospital, close to his London office.

In Cardiff, he designed a new home for the Welsh Parliament, and was invited to design one of the replacement buildings in New York for the World Trade Center destroyed on 9/11. In central London, he built a 50-storey skyscraper, the Leadenhall building (also known as the Cheesegrater), and in 2016 moved his own offices into it.

In 2015, his early notion of the Zip-Up House was partially realised in a project for the YMCA to provide houses for homeless people: they were constructed largely of factory-built panels and components.

Task force

Rogers broke rules, played with expectations and explored new methods of construction. But he had his critics. Some thought he was very bad at fitting his designs into the streetscape around them. Others found his enthusiasm for new technology and public open spaces naïve.

He was also criticised for selling out too readily to commercial interests. Number One Hyde Park, a development of hyper-expensive apartments in Knightsbridge, came in for particular opprobrium.

Meccano provided the inspiration for many of his structures

In 1985 he was awarded the Riba gold medal for architecture, and in 2007 architecture's top award, the Pritzker Prize. He was knighted in 1991. Later he became a life peer and a Companion of Honour.

In 1995, he was the first architect to give the Reith Lectures on BBC Radio. They were later published as a book, Cities for a Small Planet. In 1998, the deputy prime minister, John Prescott, invited him to chair an Urban Task Force to find ways of revitalising cities.

Meanwhile, following the collapse of his first marriage in 1973 he married an American, Ruth Elias. With her friend Rose Gray, she founded the River Café, which started as the Richard Rogers Partnership staff canteen before developing into a favoured watering hole of media types and spawning a series of cookbooks.

By his first wife Su he had three sons, and a further two by his second wife. The youngest, Bo, died suddenly of natural causes in 2011 at the age of 27.

In 2007, he said: "A very major part of my architecture is about trying to create a world which is influenced for the better through public space and private space."

By the time he stepped down from the firm he founded more than 40 years earlier, in 2020, six decades after starting out as an architect, Rogers had made his mark on many of the world's greatest cities.

Related topics

- Published19 December 2021

- Published2 September 2020