The quiet man at the British Museum

- Published

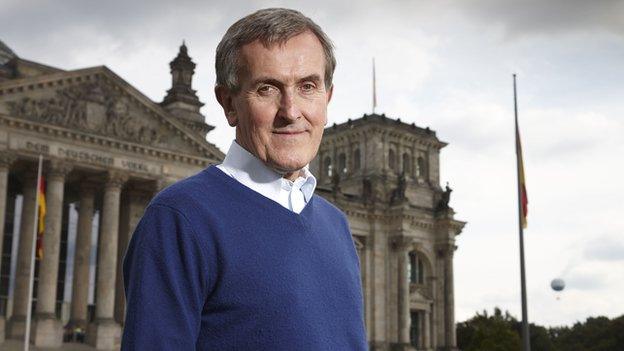

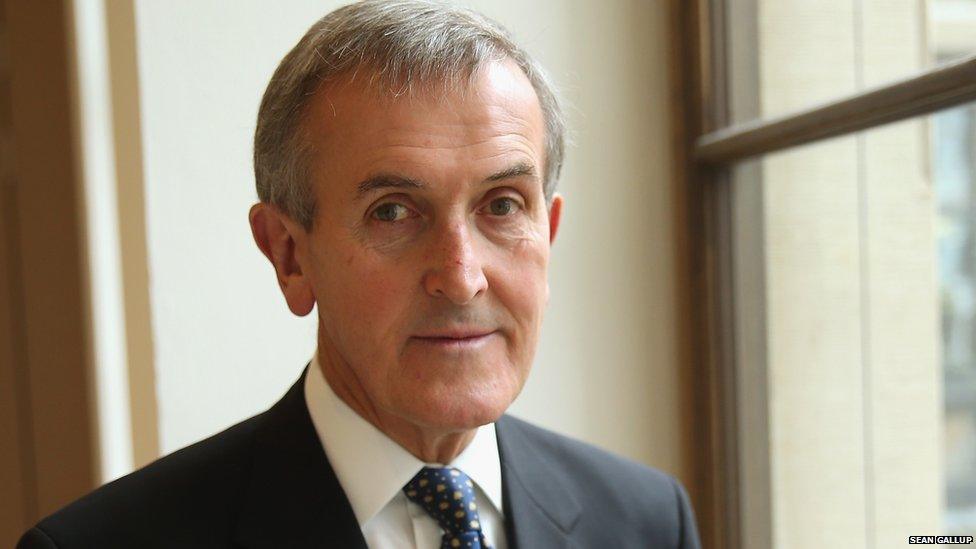

Hartwig Fischer took over from Neil MacGregor earlier this year

When Neil MacGregor was the director of the British Museum, press conferences tended to be lively affairs. He was a born raconteur who'd make his points by telling stories and cracking jokes. He had the ability - like all natural showmen - to reach out to his audience.

His successor, Hartwig Fischer, is cast from a different mould. Three months into the job, and quite reasonably still sizing up the enormity of the task, he cuts a more circumspect figure. There were no laughs or stories or great statements about future plans at his press conference this morning. Instead, a gentle earnestness prevailed.

Potentially explosive questions about BP's long-standing sponsorship of the museum, and the possibility of handing back the Elgin Marbles to the Greek authorities were diffused with the elegant evasiveness of a practised diplomat.

MacGregor presented like a charismatic teacher, Fischer's style is more akin to a professor in a tutorial: calm and assured and not in the least bit showy. Which is about right. There's absolutely no point in trying to compete with MacGregor's style or achievements, both of which won him many plaudits and millions of fans. Much more sensible for the new incumbent to try and complement the effervescent Scotsman.

Neil MacGregor spent 13 years at the helm of the British Museum

The question is how? Chatting in his office afterwards it became apparent that he was still working the answer out. The large space on the wall behind his desk is occupied by a two-metre square, black pinboard-like object - a temporary arrangement apparently, while he pauses and thinks what should go there. He's taking a similar approach to fixing his vision for the institution.

The German director has only just finished a tour of the museum's many partners around the UK, who between them ensured that 7.7 million people encountered British Museum objects beyond its Bloomsbury base (which had 6.9 million visitors) last year. He has also spent time getting to know some of his near 1,000 staff, and comprehending the huge scale of the collection, which runs into millions of objects.

There is only one moment during our discussion in which any hint of fear flickered across his eyes. It wasn't when I asked about BP, a corporate sponsorship he is grateful to have and would like to continue. Or when I enquired whether he had heard from the Greek authorities, to which the answer was an emphatic 'no' (they needn't bother - sending the Elgin marbles back, or indeed the Benin Bronzes, doesn't look like it's going to be happening on his watch).

Protest at BP sponsorship of the Sunken Cities exhibition temporarily closed the museum in May

It happened when we were talking about money. The British Museum receives 40% of its funding from the Government, and relies on its own enterprising efforts to generate the other 60%. These are impressive figures in many respects, but they do leave it vulnerable to the sort of economic volatility we are currently witnessing.

Fischer says raising that level of money is always a concern (McGregor was very good at it), and the uncertainty brought about by Brexit will present 'challenges' - hence the look of mild panic. You can understand why. A glance across the Atlantic to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, will reveal an equally venerable institution in deep financial trouble following the departure of a long-serving, much admired director, who was replaced by a relatively unknown foreigner (the Brit, Thomas Campbell).

It is impossible to know if the same fate awaits Hartwig Fischer, given that we have entered a highly unpredictable period. But I very much hope it doesn't. Not only because the British Museum is a global treasure that has found a way to share its wealth of objects and knowledge with the world, but also because the new director strikes me as a decent man with a deep intellect and compassionate outlook.

Time will tell, but on first impressions, I think we're lucky to have him.

- Published29 September 2015

- Published8 April 2015