Obituary: Brian Rix

- Published

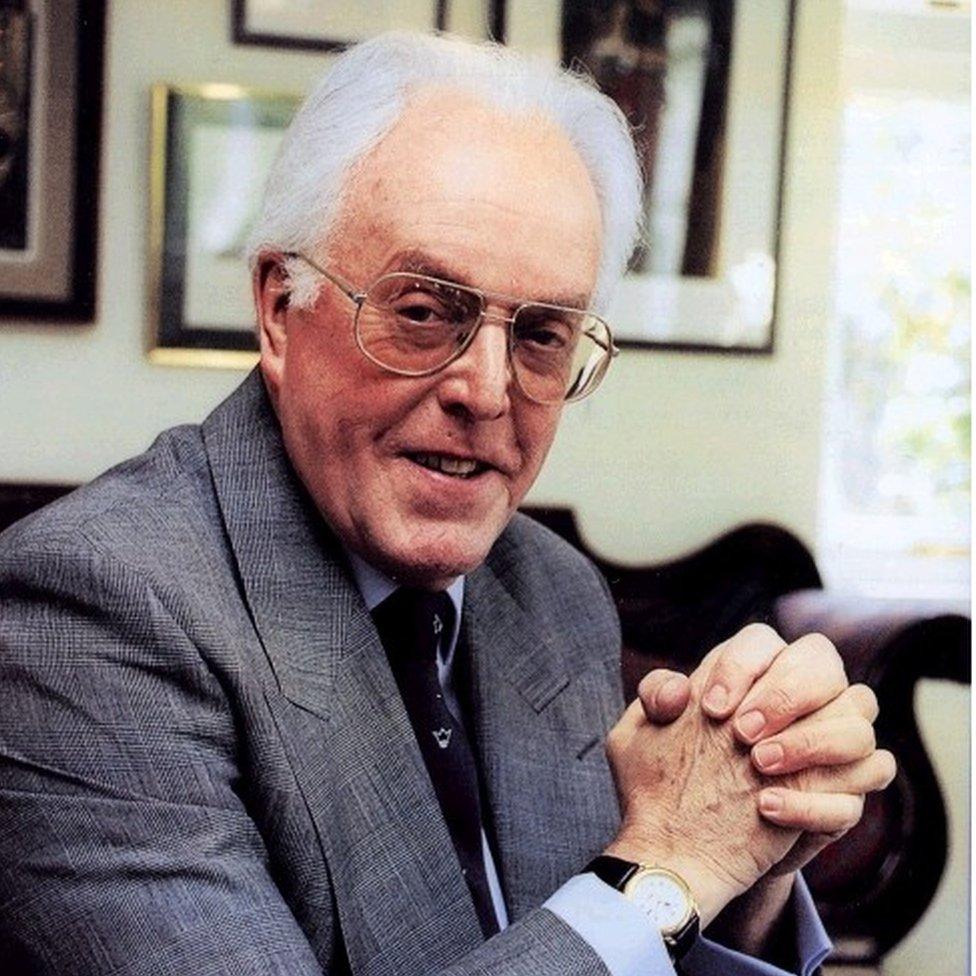

Brian Rix was one of Britain's most successful actor-managers, once described as the master of farce, and also one of the country's leading charity campaigners.

For more than three decades his farces, acted out by some of the great names in British comedy, played to packed theatres and attracted millions of TV viewers.

But the birth of a daughter with Down's syndrome saw him begin a lifetime of campaigning for those with learning difficulties.

It culminated in him becoming president of the charity Mencap and using his seat in the Lords to press for reforms in the law to provide better care and treatment.

Brian Norman Roger Rix was born on 27 Jan 1924 into a wealthy family in Cottingham in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

His grandfather, Robert Rix, had founded a shipping company in the 1860s which later diversified into the oil business.

As a talented cricketer and proud Yorkshireman he harboured ambitions to play for his county but succumbed to a love of the theatre, after appearing in plays put on by his mother who ran an amateur dramatic society.

Called up for the RAF, his service was deferred and, at the age of 18, he was performing in the theatre company run by the great actor-manager Donald Wolfit.

Within months of joining the company, Rix was playing Sebastian in a production of Twelfth Night in London.

There was a brief period in rep before he finally joined the RAF.

However, he eventually volunteered as a Bevin Boy, one of the group of men who carried out their national service as coal miners during the Second World War.

Elspet Gray became his wife, co-star and fellow campaigner

In 1947, Rix returned to the theatre and formed his own company, running a number of repertory companies, the nurseries of so many British actors.

He also married the actress Elspet Gray, beginning a personal and professional relationship that would last until her death in 2013.

Rix discovered a farce called Reluctant Heroes written by Colin Morris about army life and after touring the play, in which he starred alongside his wife, he persuaded the Whitehall Theatre in London to take the production.

Over the next 16 years Rix produced five plays at the Whitehall, including Dry Rot and One For The Pot.

They were immensely popular with audiences who loved the low comedy, exaggerated situations and bewildering plot twists.

Success

Rix was also successful in persuading the BBC to transmit a performance of Reluctant Heroes.

In doing so he had to overcome the resistance of the theatre management and the actors union Equity, both of whom saw the newfangled television as a huge threat to live theatre.

In the event television viewers loved it and the TV showing seemed to have no effect on theatre audiences, where the production continued to be booked up months in advance.

It was while playing the gormless recruit Horace Gregory, that Rix gained a reputation for losing his trousers on stage, something that would continue in future farces.

However, the BBC took a somewhat more conservative view and it was noted that the offending garments were more likely to stay on during the TV transmissions of the productions.

His farces relied on ridiculous situations, twisted plots and a dose of British smut

The success of Reluctant Heroes led the BBC to commission Rix to produce a series of one-off farces to be staged specifically for a TV audience.

The first, Love in a Mist by Kenneth Horne, was transmitted live in January 1956.

The series continued until 1972 by which time 80 productions had been successfully televised, many of them pulling in audiences in excess of 15 million.

Some of the farces were transferred to film including Reluctant Heroes, Dry Rot and Don't Just Lie There, Say Something.

Rix, who appeared in the film versions alongside comedians like Tommy Cooper, Sid James and Leslie Phillips never really felt that the film versions were as successful as the live theatre performances.

Rix quit performing in 1977, bowing out during an emotional evening at the Whitehall where he ended a period of 26 years of live performances, both at the Whitehall and at the Garrick to which he had transferred his productions in 1967.

Respite care

He was still a partner in a production company which put on a number of hit shows in the West End.

But he was missing the buzz of performing and an increasing amount of his time was being spent campaigning on behalf of people with learning difficulties, something that had started with the arrival of his eldest daughter, Shelley, in 1951 who was born with Down's syndrome.

Rix was appalled to discover that there was no support for children with this condition other than a place in an institution where there was little or no attempt to provide any stimulus, let alone education.

Both he and his wife supported a number of charities working in this field and, in the early 1960s, he became chairman of the fundraising committee of the National Society for Mentally Handicapped Children and Adults, which would later become known as Mencap.

Rix became Secretary General in 1980 and chairman of Mencap in 1988.

Ten years later he was elected president, a role he continued to hold until his death.

With fellow disability campaigner Lord Ashley

He was created a life peer in 1992 and from his seat on the crossbenches of the Lords, he introduced a bill that would ensure local authorities provided respite care for the parents of children with learning difficulties.

To his immense frustration, it took 12 years before the measure was put in place.

He also campaigned to extend statutory childcare provision for children with a disability, and fought for the right of those with learning disabilities to vote freely.

In 2006 Rix voted against an Assisted Dying Bill because he feared that people with learning disabilities might become the unwilling victims of euthanasia.

However, in 2016 he wrote to the Speaker of the House of Lords, Baroness D'Souza, and revealed he was suffering from a terminal condition, saying he hoped Parliament would act "as soon as possible" to make it possible for people in his situation to be helped to die.

"I'm not," he said, "looking for something that helps me only, I'm thinking of all the other people who must be in the same dreadful position."