Edinburgh Fringe: Why comedians need to get serious

- Published

Richard Pryor met the harsh truths of his real life head on

Back in 1967, when Richard Pryor was a 20-something stand-up, he found himself waiting in the wings of a club in Las Vegas about to go on. The house was packed. He was probably nervous and almost certainly high.

He walked on and spotted Dean Martin sitting at one of the front tables. The actor's famous face was full of boyish excitement. Pryor looked around and saw hundreds of other similarly expectant faces: eyes bright, mouths cracked open primed to laugh.

The comedian, who'd grown up in a brothel in Peoria, Illinois, paused. A series of questions went through his mind. What were they looking at? What did they want? Then he swore and wondered out loud what he was doing there.

He turned on his heel and left the stage.

That was the last anyone saw of Richard Pryor the pleasing comedian. He was done with sparkly one-liners with which he had made his name. He reinvented his act and became the man who became the legend who used profanities because they were part of his natural vernacular and not a way of getting a cheap laugh.

His old shtick built around cheesy punchlines was ditched and replaced with character-based expressionist-surrealist storytelling that met the harsh truths of his real life head on.

New generation

He changed the stand-up game. His 1970s agit-comedy would become a major influence on the UK's alternative comics of the late '80s. Rage- and confusion-veiled in-jokes became the norm for comedy clubs and hip TV shows. And then, at some point in the mid-to-late '90s, comedy stopped being serious and shifted into whimsy.

Observational became the thing - telling insights from world-weary flaneurs whose stock-in-trade was to point out the ridiculousness of everyday life. And that's how things have been pretty much ever since for the really big stars of comedy, from Larry David and John Bishop to Al Murray and Amy Schumer.

Nothing wrong with that, they are all class acts. But right now they feel part of something that was, as opposed to something that is. The momentous, calamitous, tragic, and mind-warping nature of world events over the past 12 months has changed things. At least, they have for me.

I found myself sitting at a comedy gig at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe the other day and having a Richard Pryor moment. It was a decent show, by an established comic, musing on the vagaries of life. It was funny and well observed but all I could think was, what am I doing here?

I wanted something different. A comic who would use his or her wit to interrogate some of the big issues we're facing.

Shazia Mirza: 'I'm female, I'm brown, I'm Muslim and people want to know what I think'

Matt Forde's Edinburgh show is titled It's My Political Party (And I'll Cry If I Want To)

I don't think I'm alone. Many of the agents and impresarios to whom I have spoken over the last few days have identified a notable change in what Fringe audiences are looking for. The punters want politics.

I've been a fan of Matt Forde's political satire for a while, but his new show has an added sense of energy and urgency post Brexit. Last year you didn't have to book to see him, now you'd be wise to do so - he's playing to packed houses.

Shazia Mirza, a stand-up comedian who hails form Birmingham, summed up the mood when she told me: "It's different this year. I could talk about my moustache… but I'm female, I'm brown, I'm Muslim and people want to know what I think."

She has put on a good show that directly confronts the news agenda and associated issues.

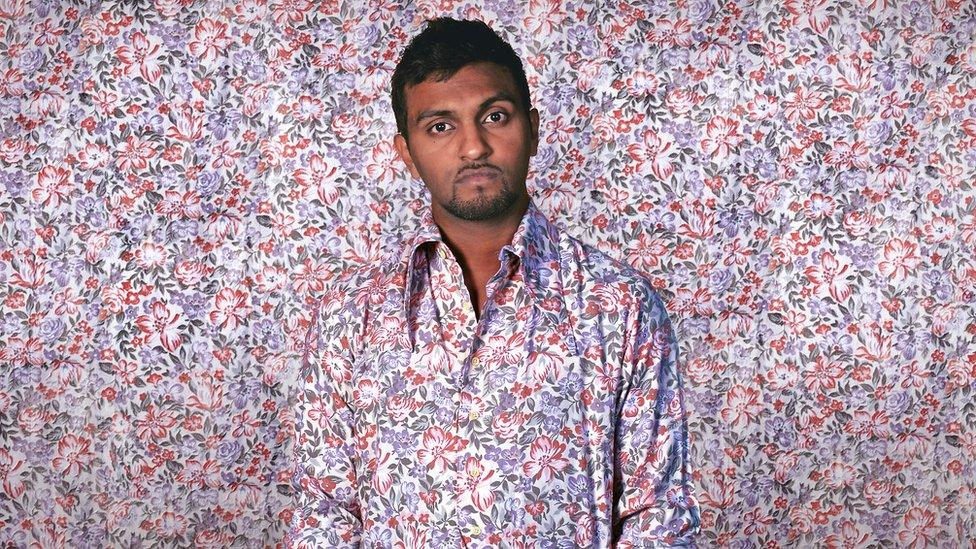

Nazeem Hussain: 'Awkward, aggressive, uncompromising and funny'

But the stand out stand-up for me this year is the Australian comic Nazeem Hussain, who is performing here for the first time as a solo artist.

He doesn't so much tackle the tricky subjects head on (being an Asian-Australian, being a Muslim, being the subject of covert government surveillance), but drags them out front and gives them a good beating.

"What do you want to talk about?" he asks the audience, and then without waiting for an answer: "Isis? OK." And off he goes, developing a narrative that is delivered like a rant, but is actually a carefully crafted assessment of how he sees things. It's awkward, aggressive, uncompromising and funny.

He's good. Not quite Richard Pryor good, but not far off.