Oscar Wilde love letter celebrated 'behind bars'

- Published

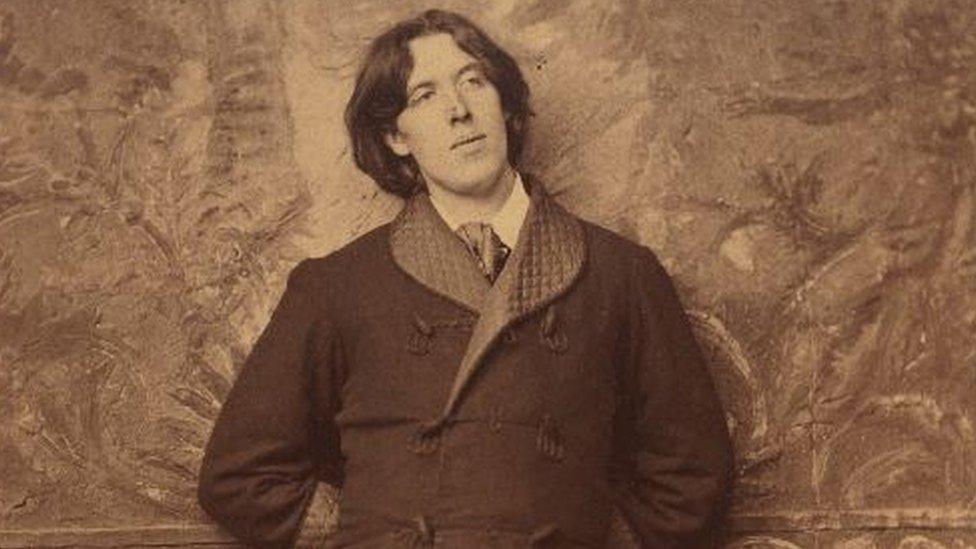

Oscar Wilde wrote his epic letter De Profundis during his two-year sentence in Reading prison

In 1895 Oscar Wilde was sent to prison following the most infamous of indecency trials. His two-year term was served mainly at the now closed Reading prison, then known as Reading Gaol. It was there he wrote De Profundis - a long letter to his young aristocratic lover. Weekly readings of it by well-known actors and writers have just begun at the former prison. One of the readers, poet Lemn Sissay, went to meet the great-grandson of the man regarded as Wilde's nemesis - the 9th Marquess of Queensberry.

At 86, the 12th Marquess of Queensberry, or Lord Queensberry (first name David), is long retired from a career as Professor of Ceramics at the Royal College of Art. But his house in London is filled with paintings and pottery and an obvious love of art.

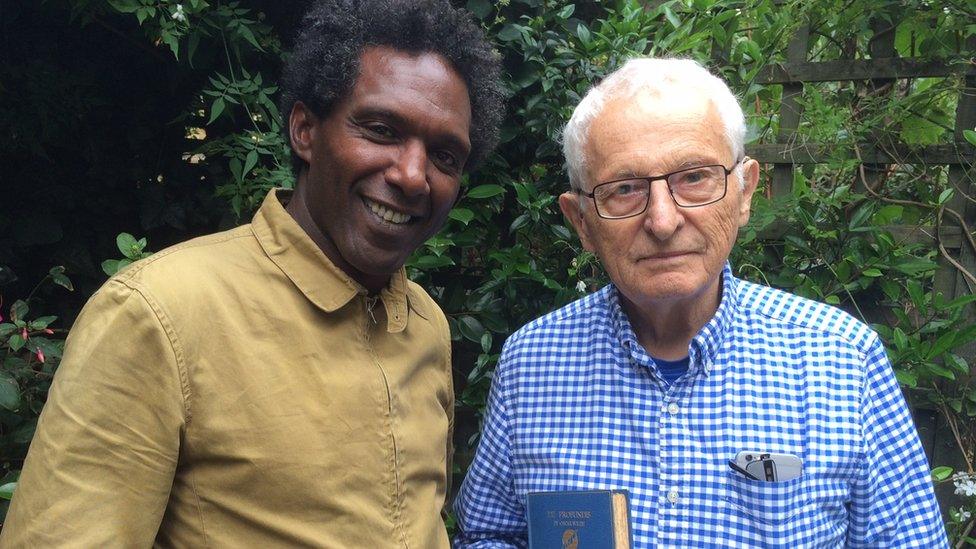

Lord Queensberry is delighted to invite into his kitchen the poet Lemn Sissay, one of the figures who for the next few Sundays will read De Profundis where it was first written, in the former Reading prison.

The title means From the Depths. Though in theory a letter to his former lover Lord Alfred Douglas (known as Bosie) it reads as a long essay on life, art and religion. Others scheduled to perform it include Maxine Peake, Ben Whishaw and Patti Smith.

In most cases the Sunday readings, which are largely sold out, are in the prison chapel. But Irish novelist Colm Toibin will read from the same cell where Wilde served the sentence which helped propel "Prisoner C33" towards an early death at 46.

Lord Queensberry (right) told Lemn Sissay he was 'absolutely not an apologist for my great-grandfather and never have been'

The project is the work of the organisation Artangel and includes artwork by the likes of Steve McQueen and Marlene Dumas.

Which brings us back to the current Lord Queensbury and his art-filled house.

No one could be less like the Victorian ancestor often portrayed as a maniac intent on destroying Wilde at any price. But Lord Queensberry is keen to give Sissay the background to the work he's about to perform.

"I'm absolutely not an apologist for my great-grandfather and never have been. There were times when he was a monster. But I'm not the only person who thinks his son Bosie was the real villain. In later life Bosie became something of a homophobe and some of his statements were racist."

Lord Alfred Douglas died in 1945 and Lord Queensberry recalls meeting him. "It was fleeting and we never had a proper conversation. But I know my father helped him financially: at times Bosie was pretty well penniless."

Faced with the daunting task of reading all of De Profundis to an audience, Sissay is keen to understand more about what led to a work theoretically addressed to Bosie.

Lord Queensberry believes Oscar Wilde knew sending his letter to Bosie (right) would have been pointless

"It's not always easy going," he admits, "but with Artangel I committed to reading the whole thing which will take around four hours. I could have gone for a condensed version but it's a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the reader and the audience.

"It's like becoming Chancellor of the University of Manchester last year - it's important for writers to be involved in things beyond their own little world."

Wilde was discreetly allowed to write his manuscript by a sympathetic prison governor. But Lord Queensberry believes Wilde came to see that sending it to Bosie would have been pointless.

"Probably Bosie would just have put it on the fire. It's not very flattering to him - certainly not the full version which emerged after he died."

Neither he nor Sissay doubts that Wilde was in love with Bosie but Lord Queensbury says Bosie's motivations were complex.

The cell which held Oscar Wilde will become an unlikely setting for a literary recital

"People sometimes forget the entire thing started when Wilde was prevailed upon to sue Queensberry for criminal libel. The Marquess accused him of being a 'somdomite' as he put it - spelling isn't always our family strength. It was Bosie who wanted him to sue: if he had a dream it was to see Queensberry carted off to jail. Bosie wanted to stand in the witness box and denounce his father.

"We can't say he didn't love Wilde but Bosie was certainly manipulative. He persuaded Oscar to deceive his own legal counsel about their relationship: if the truth had been clear the lawyers would have seen disaster was almost inevitable.

"You do get a self-pitying streak in De Profundis, which annoys some people. But after what Oscar went through I suppose we might forgive a little self-pity."

Sissay admires the fact that much later Lord Queensberry, as a member of the House of Lords, spoke in favour of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. The legislation legalised homosexual acts in private between consenting adults aged at least 21 in England and Wales.

"It was a huge step for gay men but it was a real step for all of us."

Lord Queensberry says half a century ago he was delighted to associate his family with a liberalising measure. "The Queensberry name had become so associated with the way Oscar Wilde was pilloried in 1895. However much I disapprove of what Queensberry did, he was using the law as it then stood.

"My regret with the 1967 act was that we settled for a high age of consent. But it was the only way to get it through parliament. Today if you read some of the objections my fellow peers made at the time they sound extraordinary.

"I have family and close friends who are gay and for most people it's just not an issue. It's been a remarkable change in my lifetime."

Sissay is looking forward to his stint reading De Profundis on 18 September.

"It's not only the work itself - though I'm finding new things in it all the time. It's also being part of people's fascination with Wilde, which never seems to vanish. It was too late for him but a lot of attitudes were changing by the sixties - and not just to sexuality. De Profundis is a reminder of how bad things were for far too long."

Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison continues until 30 October.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, on Instagram, external, or if you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.