Streaming playlists 'make it harder to break UK talent'

- Published

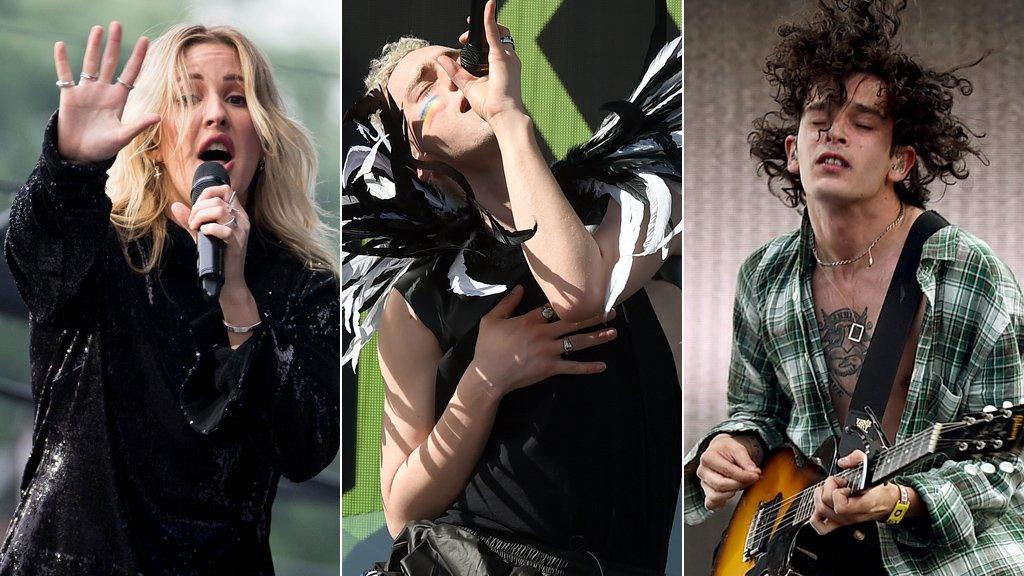

Polydor has had success with acts like Ellie Goulding, Years & Years and The 1975

The president of Polydor Records says British record labels are struggling to establish new artists because of the way streaming services promote music.

"Playlists are skewed towards US artists, which makes it harder to break UK talent," Ben Mortimer told the BBC.

"I love streaming. Everyone knows this is happening and we're working 24-7 to figure out how we can fix it.

"It's a conversation that's going on in rooms in every streaming service and in every record label."

Only one British artist - Zayn Malik - has had a number one single in the UK this year.

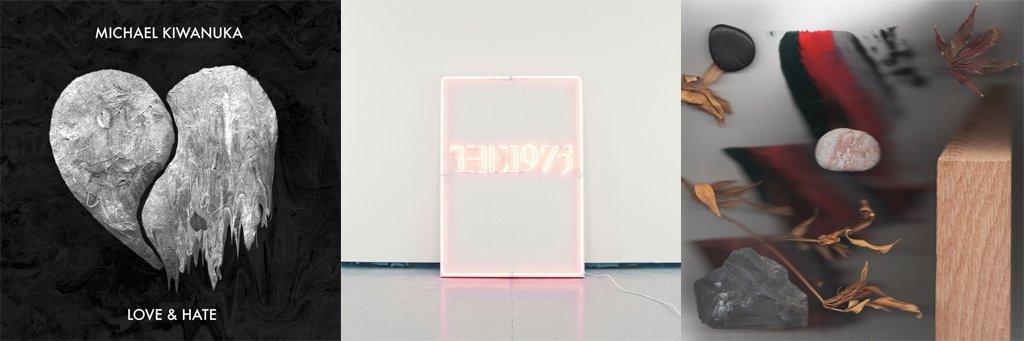

Mortimer, whose label has three albums shortlisted for tomorrow's Mercury Prize, says acts from North America are particularly strong at the moment.

"We're inundated with absolutely brilliant pop and urban music from the States," he said.

In a first for a major label, Polydor has three nominations for this week's Mercury Prize

"But look back over the last six or seven years, the UK has been the country that's dominated the global music scene - from Adele to Florence to Ed Sheeran to Mumford and Sons. It has been relentless and people in America have been worried for their jobs.

"It just so happens they've got their stuff together over there. It's a cyclical business in that way."

Nonetheless, 2016 has been notably quiet for new talent, with the likes of Drake and Justin Bieber dominating the charts at the expense of new releases.

The inclusion of streaming data, where 100 streams equals one sale, means the Top 40 now rewards music that is being listened to repeatedly.

The situation has led to an unprecedented slowdown in the singles chart. Just eight songs have reached number one in the UK so far this year, compared with 17 at the same point in 2015; and 28 the year before.

Olly Murs recently complained about the impact of streaming playlists on his chart position

Many in the music industry believe playlists like Spotify's Global Top 50 and Apple Music's Top Songs are self-perpetuating - robbing new music of much-needed exposure.

Pop star Olly Murs recently said the charts were "not fair" after his single, You Don't Know Love, stalled at number 15.

"With streaming you have to be on certain playlists for it to have effect," he told Digital Spy., external "I feel like the chart now, for breaking new artists, is harder."

Mortimer, who signed artists like Jamie T, Years & Years and Florence + The Machine, said the UK was still producing "tons of great music" and that labels like Polydor would continue to invest in "brilliant artists".

Read more of his interview below.

How do you account for your success at the Mercurys?

Polydor has a strong heritage of brilliant music, from the 60s onwards. It's always been a music-first label, and that's something we've been taught to instil here.

To have three Mercury nominations in one year, especially with sophomore [second] albums, shows real artist development. [We have] a light touch, allowing the artists to be creative and backing them.

Michael Kiwanuka's album took a lot of people by surprise - he'd almost been written off after his debut failed to sell in big numbers. Was there pressure on you to drop him?

I'd be lying if I said those conversations don't happen with some artists - but with someone like Michael, who I believe is close to being considered a classic artist, it's our responsibility to back them and show the support they deserve.

One of the major problems in the UK is that people are expected to come out on their first record and be as good as Blur or U2 - but those bands broke on their third record.

What's your philosophy when you sign a new band? What are you looking for?

Before, when we used to sign people, it would be on a demo and a gut feeling, but now you've got so much more information. Often bands have a bit of a fanbase already, or you can see how well their tracks are doing online.

Those stats can be misleading, though.

Exactly, and you have to be careful of that. Just because something's big on the internet, doesn't mean it's going to be big in the wider world. The balance is going a bit on that gut feeling, but using a touch of the stats.

One thing that hasn't changed is that you still want to sign brilliant artists, charismatic people and great songwriters.

Ben Mortimer (right) is co-president of Polydor Records alongside Tom March (left)

The traditional view of A&R is Alan McGee watching Oasis at King Tut's and offering them a deal on the spot. How realistic is that?

It's such a lovely idea - and I definitely caught the tail end of those years in my early days.

To some extent, that can still happen. A recent example is Royal Blood, a band who didn't have much going on, but an A&R at the back of the room said "you're signed" and it grew from there.

Why are guitar bands struggling so much at the minute?

I think people really love what the Americans call "rhythmic music" at the moment. There's a love for pop music, and urban music is just huge - just pouring out of the US and Canada. It just feels like the tide is not with guitar music.

It's been that way for almost a decade now.

It has - but I remember being here in the late 90s, when dance music was huge, and then it disappeared for much of the following decade. These things happen in cycles.

The Strokes prompted a sudden shift in the music market at the start of the millennium, says Mortimer

It's your job to be ahead of that curve… so how does a sea change like that manifest itself to you? Or does it catch you by surprise?

It definitely can do. Back in my previous life, I worked as a music journalist. I remember sitting in the offices of Mixmag and a young lady on the news desk started talking about an album from a band called The Strokes in New York.

Most of the people in the office went, "that's a load of rubbish", but it changed music for the next six or seven years.

So these things come along - we just have to be looking out for them.

You've just signed up the editor of GRM daily, Elle Simionescu-Marin, to your team. Are you pinning your hopes on grime as the next big thing?

Is grime the next massive youth movement? It already is, to some extent.

I just think it's great to have brilliant people around you, and she's a brilliant, enthusiastic and well-connected woman.

Is it simply the case that it will take more effort to break artists in the future?

Exactly. You have to put out more music and put on more shows before you get noticed. But that's not necessarily a bad thing. It's what the Beatles did. They were tucked away in Hamburg for two years learning their craft, then they were great when they came out.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external, or if you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published17 July 2016

- Published4 August 2016

- Published4 August 2016