Bob Dylan: Singer, songwriter, literary great

- Published

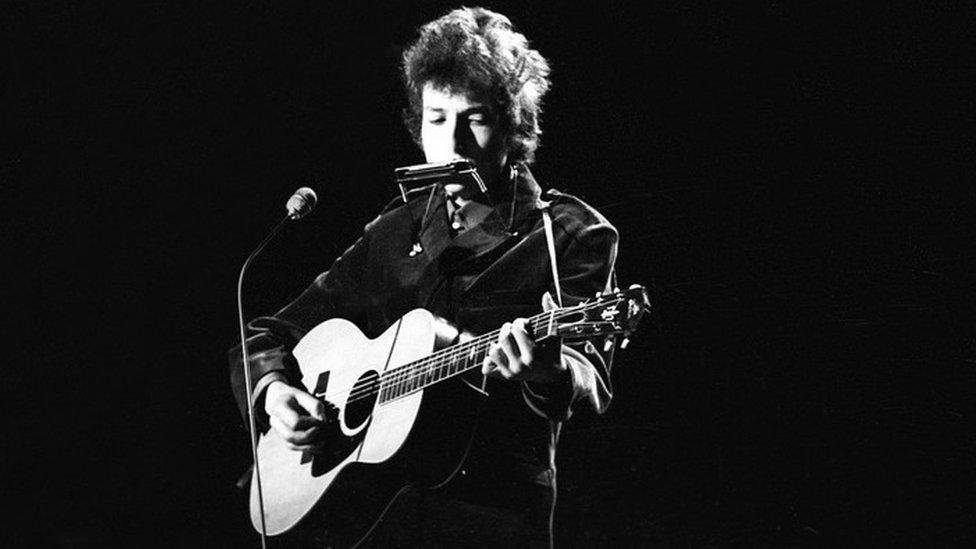

Bob Dylan pushed the art of songwriting to a new level

Bob Dylan is one of the greats of modern music - but he has never won any prizes for his voice.

Instead it is his lyrics and songwriting that have changed rock and pop music and earned him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

As the austere 1950s gave way to the free-wheeling '60s, Bob Dylan was the voice of his generation - the original singer-songwriter who both led and chronicled the social revolution that changed the world.

He has never had the greatest voice by traditional standards; indeed, that was part of his appeal. But he did create a new template for the singer as a poet and artist.

'Greatest living poet'

Allen Ginsberg called him the greatest poet of the second half of the 20th Century and former Poet Laureate Sir Andrew Motion has said he listens to Dylan almost every day.

On Thursday Per Wastberg, chair of the Nobel literature committee, said he is "probably the greatest living poet".

Certainly no other rock musician has had their lyrics more analysed, anthologised and eulogised.

After the 1950s, in which pop music had been dominated by the likes of Elvis Presley and Buddy Holly, Dylan was a free spirit who drew on literary influences to convey the political mood of the time.

And he delved into his inner self to summon songs that set the blueprint for the confessional singer.

His anthemic melodies, unorthodox voice and ruffled appearance were big parts of his appeal to the new, liberated generation.

But that alone would not have been enough to touch so many so deeply, let alone be recognised by the Nobel panel.

Dylan often shunned questions about the meaning of his work

In a speech accepting an award last year, he explained: "These songs of mine, they're like mystery stories, the kind that Shakespeare saw when he was growing up. I think you could trace what I do back that far."

The young Dylan was heavily inspired by poets like Arthur Rimbaud and John Keats, and his poetic influence is even in his name.

When Robert Zimmerman began performing folk songs in coffee houses, he renamed himself after Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

He was also influenced by dustbowl "folkies" like Woody Guthrie and country star Hank Williams. Yet Dylan moved beyond their traditions.

Meanwhile, the Cold War was at its height and America was racked by internal turmoil as the burgeoning civil rights movement clashed with the conservative middle class.

It was Dylan who would provide the musical backdrop to these troubled times.

Not just a protest singer

Using simple chords and universal metaphors, Dylan managed to tap into the zeitgeist of the era like no other, bridging the gap between folk and mainstream pop with songs such as Blowin' in the Wind and The Times They are A-Changin'.

Tunes including Like a Rolling Stone, Just Like a Woman and Lay Lady Lay followed as the 1960s went on, and Dylan easily moved beyond the pigeon-hole of protest singer.

The songs became anthems and were covered by hundreds of artists.

When he "went electric" at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, he horrified the assembled audience in one of the seminal moments in music history.

The sweet folk troubadour had transformed himself into a hedonistic rock star, with trademark dark glasses hiding eyes glazed by drink and drugs.

After a motorcycle accident and a subsequent seclusion, he made a comeback in the mid-1970s.

It culminated in 1975's Blood on the Tracks album, largely inspired by the break-up of his marriage and hailed as a return to form.

Career comebacks

Three years later, after Dylan witnessed a vision of Christ in an Arizona hotel room, his lyrics became full of Biblical references and reflected themes of faith and morality.

His albums continued to be received with interest - if often mixed reviews - and in 1988 he began what came to be known as the "Never-Ending Tour", constantly reinterpreting his own songs on stage.

Just as it seemed he was losing his relevance, his 1997 album Time Out of Mind, with its dark themes of mortality, proved another landmark release. It won three Grammys including best album.

In 2006, at 65, he became the oldest living artist to enter the Billboard chart at number one with Modern Times.

As he slipped into legendary status, an avalanche of honours flowed: A Kennedy Center Honour, an Oscar, a Pulitzer Prize, a Golden Globe, the Presidential Medal of Freedom - and, most recently, a Nobel Prize.

He was awarded the prize in October and is accepting it in Sweden this weekend.

Dylan has also published books, like 1971's experimental Tarantula, the collection Writings and Drawings and the autobiography Chronicles.

But it is the poetry in his music that has earned him the literature world's highest honour.

Follow us on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external, or if you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published13 October 2016

- Published9 February 2015