Did ye get healed? - How Van Morrison's music helped me recover my life

- Published

I have a special connection to an enigmatic Belfast man whose music crosses jazz, blues, folk and rock.

In the late 1980s, I was held hostage in Beirut. Of my five years in captivity, four were spent with the Irish writer Brian Keenan.

Stripped of virtually all external stimuli, we had to keep our minds and hearts going with memories.

Two lonely men, we shared things that had touched us - books, films and music.

Our soundscape then was as blank and depressing as the concrete walls of our cells. But music would emerge from our memories and we would hum snatches of songs as they came to us.

Brian talked of traditional Irish music and of the great Belfast musician Van Morrison.

I had never seen Morrison in concert but knew some of his hits - Brown Eyed Girl, Gloria and Moondance.

But as Brian spoke, I somehow I felt as though I had stood with him in a crowded Belfast concert hall watching Morrison leaning into the microphone as he sang one of his soulful ballads - or throwing himself about the stage like a wild man, overwhelmed by the power of the music.

Another world

Morrison is only a few years older than Brian and was born only a few streets away in East Belfast.

They went to the same school and came from the same modest backgrounds. Morrison's father had been a shipyard worker and they had grown up in near identical, small terraced houses. However, only a short walk away, was another world, a street lined with large villas called Cyprus Avenue.

Morrison wrote about it on a track on his seminal album, Astral Weeks. Brian took me to these streets for the first time to record a BBC radio documentary, Van Morrison and Me.

Two years ago, Morrison played a concert on Cyprus Avenue which Brian attended.

He dedicated the song "Motherless Child" to Brian, something he has never forgotten and which deeply moved him.

"It's a song which has a very special significance for me. Chained to a wall, never knowing if you were ever getting out, ever going home, your whole sense of who you were evaporated. And you felt lost and lonely, a bit like a motherless child," Brian said.

When I was finally released in 1991, I strove to come to terms with what had happened with the help of my girlfriend Jill Morrell, who had been campaigning constantly for my release.

We settled in a cottage in the Oxfordshire countryside and Morrison's music became a key part of our liberation soundtrack.

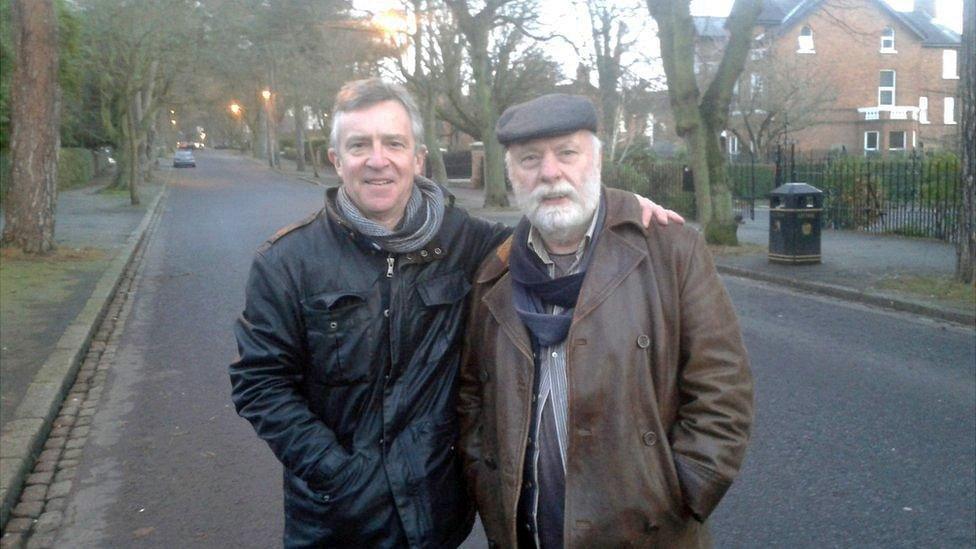

John McCarthy (left) and Brian Keenan on Belfast's Cyprus Avenue

Jill and I tried to make sense of those extraordinary times, writing a memoir of my captivity and her campaign.

One song particularly touched us both, and that was Wonderful Remark.

I remember one night getting a magnifying glass to read the lyrics crammed onto the cassette's sleeve notes.

As I read, I was stunned. Morrison's words seemed to capture the emotional heart of our experience over the hostage years: "How can you stand the silence, that pervades when we all cry? How can you watch the violence that erupts before your eyes?"

How did he come to write that?

I had met Morrison once or twice since my release at charity events and hoped that personal connection might help persuade him to speak to me about his music.

So I was delighted when he agreed to meet me at the Culloden Hotel, a beautiful former bishop's palace on the outskirts of Belfast. When I asked him about Wonderful Remark, he told me that it was a song about hard times he had suffered in New York.

He was short of money and felt stranded, a situation which contrasts to mine. But we both experienced similar feelings of frustration and sadness, as Morrison explained: "It was a song about my circumstances but it was nothing compared to what you've been through. It was about people who were supposed to be helping you and they weren't there.

"It was about the business I'm in and the world in general. A lot of the times you can't count on anybody."

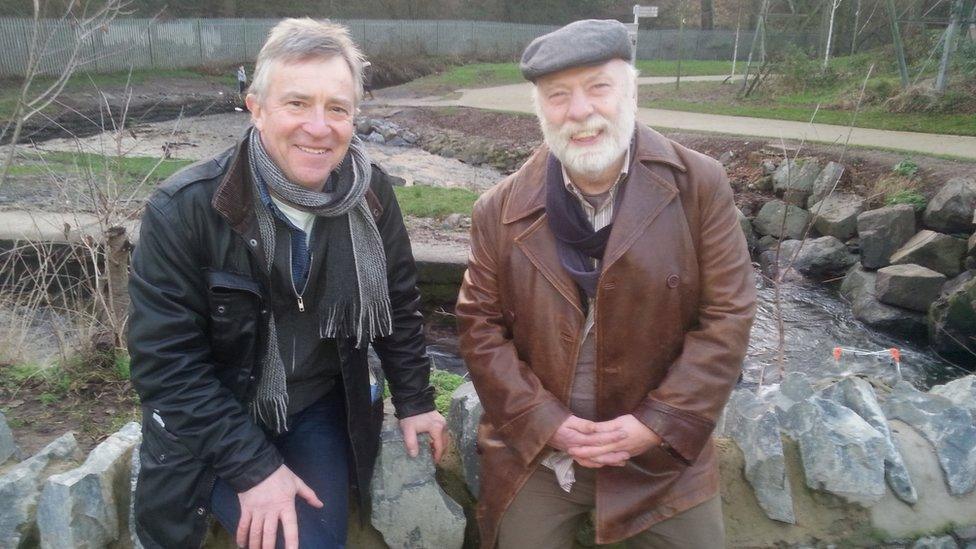

John McCarthy and Brain Keenan by Belfast's Beachie River

Brian took me from Cyprus Avenue to other locations which feature in Morrison's songs. Hyndford Street, where Morrison grew up and the nearby Beachie River.

Brian told me he used to go there as a boy with his father: "If we missed school, we'd go round there and catch frogs and newts. And it was a place where you could go courting where nobody could see what you were up to."

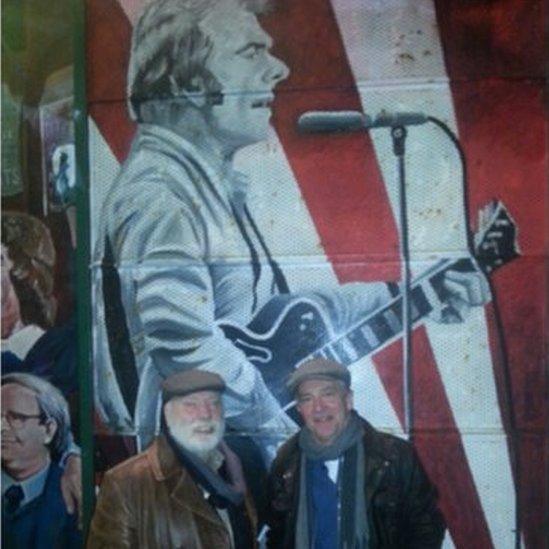

John McCarthy and Brian Keenan next to a mural celebrating Belfast's most famous musician

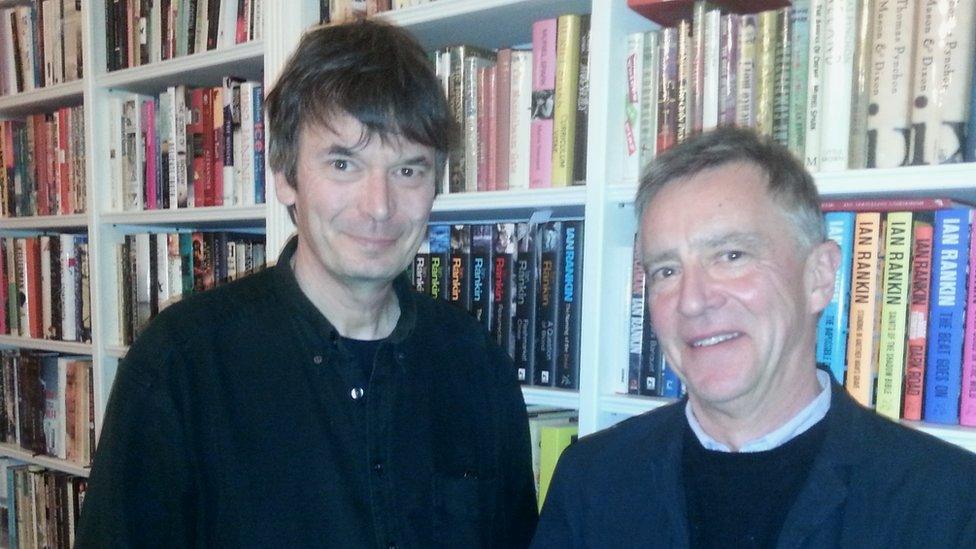

John McCarthy (right) and author Ian Rankin

Ian Rankin is another writer who says he has been influenced by Morrison's music at an important moment in his life.

In his mid-20s he was living in London, frustrated that he was not making progress as an author.

He told me how, after suffering panic attacks, his doctor advised him to rest.

So he grabbed a handful of Van Morrison cassettes and caught a train up to Scarborough to reflect on his life.

"It's very personal music and I thought here's someone who understands something of what I'm going through, they've seen highs and lows," he said.

While Wonderful Remark is the stand-out Morrison song for me, Ian was most influenced at the time by tracks from Morrison's 1973 album Hard Nose the Highway: "What I learnt was something about ploughing your own furrow. Don't let the world get in the way, if you want to be a writer, be a writer."

Ian decided to move to France to concentrate on writing novels. He has since written 21 Inspector Rebus books and become a world-famous author.

Van Morrison - Sir Van Morrison now - is rightly regarded as one of the truly original songwriters and performers of his generation.

His official accolades include two Grammys and an Ivor Novello award. One song - Someone Like You - has appeared in no less than seven Hollywood movies.

But the real accolades are from the millions of people, like me, who have, time and time again, been moved by his songs.

When I asked him how he had managed to touch so many people's lives, he said it was about working with the natural talent with which he had been born.

"I think it comes from God, whatever that concept is. A lot of people are given gifts and they don't develop them. I thought because I was given this gift, I had to develop it."

You can listen to John McCarthy reflect on Van Morrison's influence on his life on BBC World Service at 14:06 GMT on Saturday or on demand afterwards via iPlayer Radio.

- Published31 August 2015

- Published31 August 2015

- Published31 August 2015

- Published12 June 2015