Raymond Briggs obituary: An illustrious career

- Published

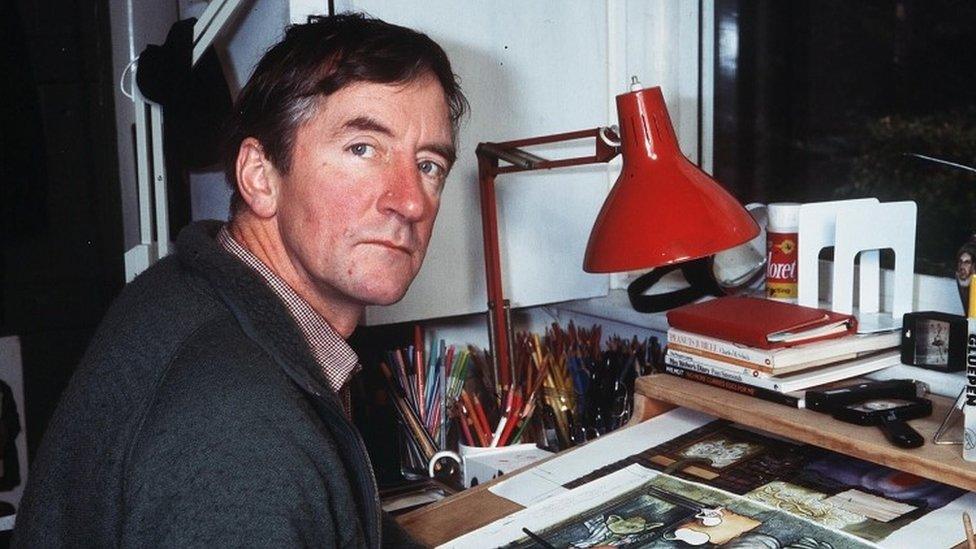

Raymond Briggs used his skills as an illustrator to articulate his own acerbic views on people, politics and society.

His children's books often failed to follow the established format. His snowman melted and his Father Christmas was far removed from the jovial figure we all expect.

An astute observer of the human condition, his adult work reflected his own concerns, such as When the Wind Blows, a fable about a nuclear attack on the UK.

Many of his books were made into successful films, winning him a string of awards and the admiration of millions of fans.

Raymond Redvers Briggs was born in Wimbledon Park in London on 18 January 1934. His father, Ernest, worked as a milkman while his mother, Ethel, had been a lady's maid before her marriage.

He was not particularly interested in children's books, apart from the Just William stories of Richmal Crompton. "It was always such a letdown at Christmas to feel that horrible hard edge under the wrapping paper," he later recalled. "I much more wanted a toy or a gun or something."

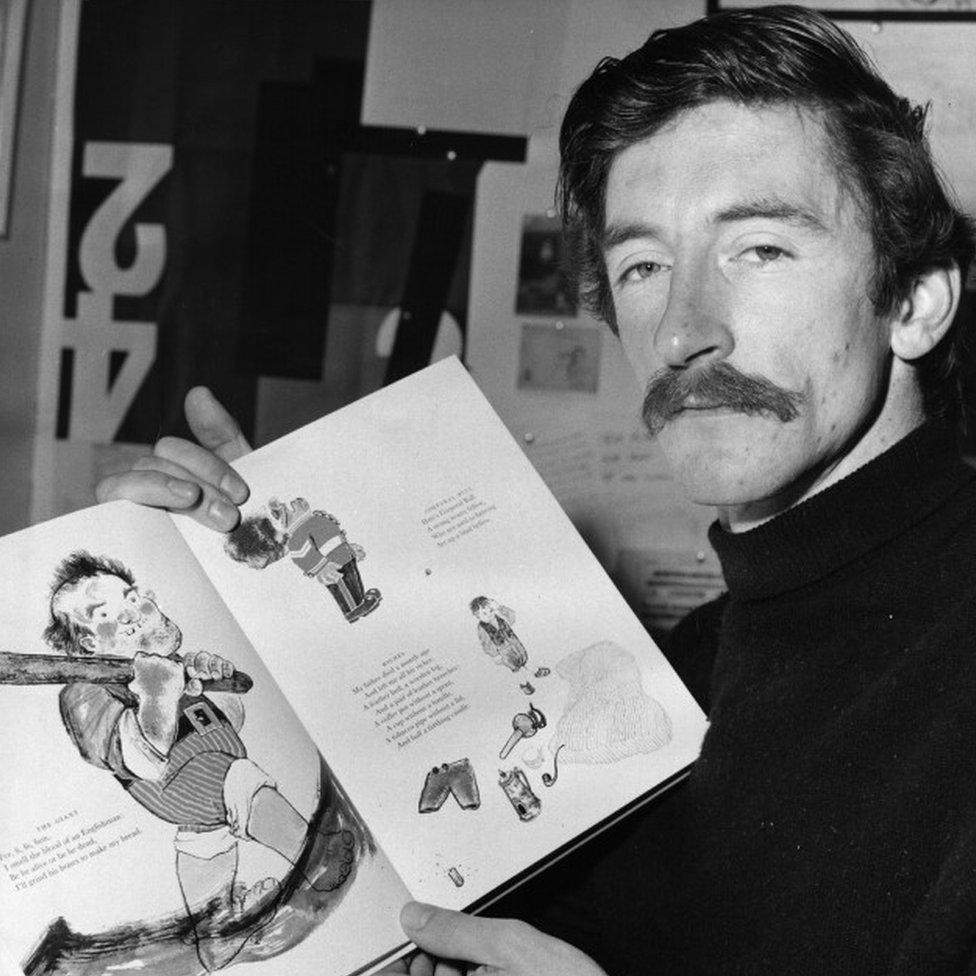

He won the Kate Greenaway medal for his Mother Goose Treasury illustrations

At the outbreak of World War Two he became an evacuee, returning to London to take up a place at Rutlish Grammar School, which he found "awful and snobbish".

In 1949, he went to the Wimbledon School of Art with the ambition of pursuing a career as a cartoonist, despite the opposition of his father who wanted him to take up a more lucrative profession. However, his art school interviewer considered cartoons the lowest of the low, and the young Briggs found himself studying painting.

He was conscripted into the Royal Corps of Signals for his national service where, like many artists, he was given a role as a draughtsman and set to drawing electrical circuits, much to his disgust.

Fairy tales

After his demob he went to the Slade School of Fine Art, from where he graduated in 1957 and set out to make a living as an illustrator. Having tried advertising "which I loathed even though the pay was ludicrously huge", and magazines, he moved on to children's books which he soon grew to love.

His first major work was to illustrate an anthology of Cornish fairy tales, Peter and the Piskies, which was published in 1958. They were collected by Ruth Manning-Sanders, who later used Briggs on another of her collections, The Hamish Hamilton Book of Magical Beasts.

He soon found himself much in demand as a children's illustrator but was often disappointed by what he felt was the poor standard of the text. In 1961, he wrote The Strange House, and gave it to an editor friend hoping for some constructive criticism. Instead, the editor had it published. He also got a part-time job as a lecturer at Brighton School of Art which helped him survive when commissions dried up.

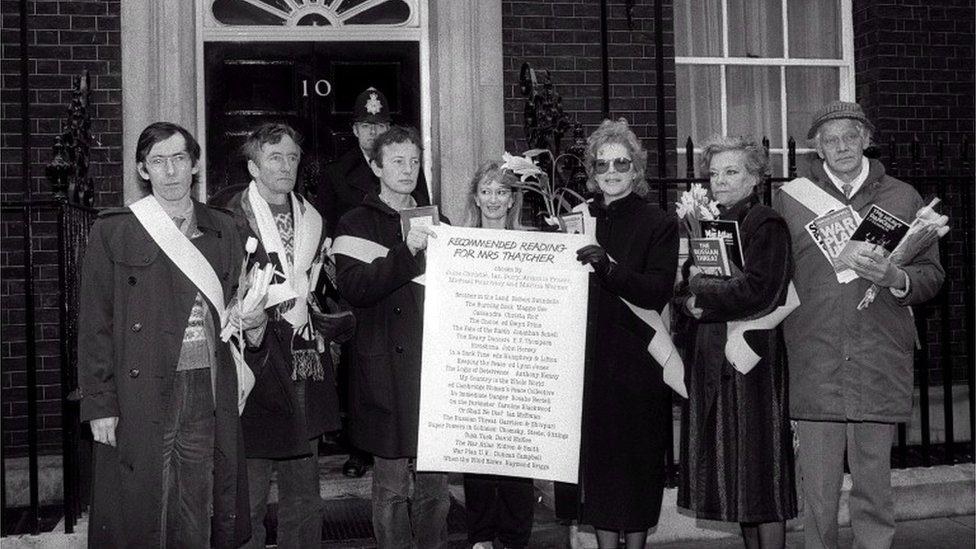

Briggs (2nd left) joined other authors in an anti-nuclear protest in Downing Street

He won his first major award, the Kate Greenaway Medal, in 1966, for his 800 illustrations in The Mother Goose Treasury, a collection of fairy tales and nursery rhymes.

Jim and the Beanstalk, published in 1971 was a reworking of the old fairy tale, characterising the giant as a somewhat grumpy but sympathetic figure who read a lot of poetry, a description that could have been applied to Briggs himself.

His breakthrough came in 1973 with the publication of Father Christmas. Briggs had become frustrated with the traditional children's story book format and instead turned it into a strip cartoon, a novel idea for children's books at the time.

Fell flat

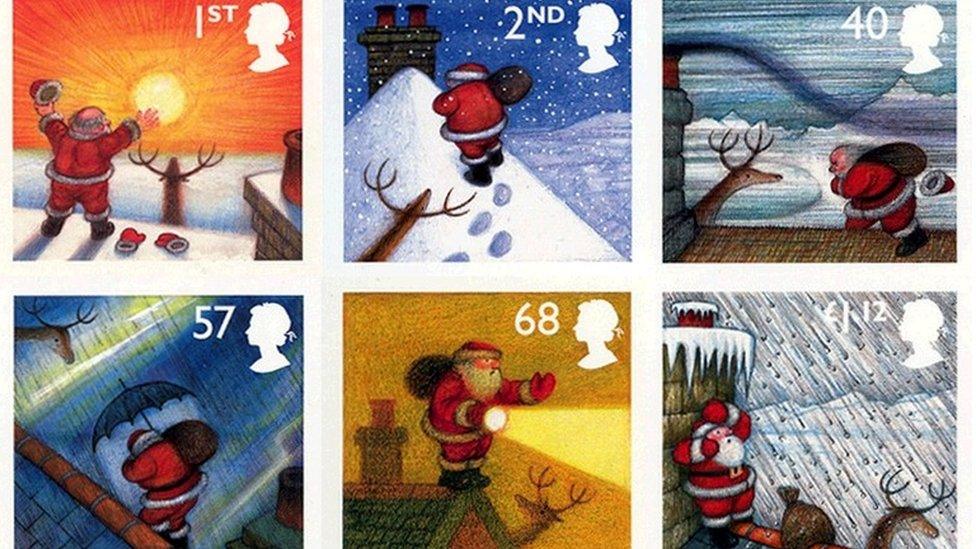

His portrayal of a Father Christmas, overworked, curmudgeonly and always complaining about the weather, in particular the "bloomin' snow", proved an immediate hit, winning him a second Kate Greenaway Medal. Both it and a 1975 sequel, Father Christmas Goes on Holiday, were later adapted as animated films with comedian Mel Smith voicing the eponymous character.

Fungus the Bogeyman, published in 1977, became an instant classic, despite, or possibly because of the nature of the protagonist, whose sole job in life is to go around scaring people. Children always like monsters.

Briggs made great use of wordplay and recalled poring over dictionaries for "bogey-like words" he could incorporate into the text.

Various attempts to film it fell flat because of the complete lack of plot but the BBC did air an adaptation in 2004 starring Martin Clunes and Clare Thomas.

In 1978, Briggs produced his best-known work, The Snowman. A picture book without text, it told the story of a boy who built a snowman that came to life but the friendship ended when the sun rose in the morning and the snowman melted.

It was turned into an Oscar-nominated, Bafta award-winning film although the screen writers took a great deal of liberty with the original text, transforming it into a Christmas story which the original book never was.

Ridiculous advice

The launch of The Snowman film in 1982 coincided with the publication of the adult-themed, When the Wind Blows. Featuring a retired couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs, who had first appeared in a previous work, Gentleman Jim, it describes a Soviet nuclear attack on Great Britain and the aftermath.

Briggs used the tale to pour scorn on government pamphlets advising people what to do in the event of a nuclear attack, many of which were just updated versions of information originally issued at the time of the Blitz. The couple follow the instructions and eventually die of radiation sickness.

The book caused uproar, with Briggs being accused of peddling CND propaganda and having one critic describe the work as "sentimental, absolutist, naive and entirely missing the point".

The Snowman became his most popular work

"I wasn't even in CND at the time," Briggs later protested. "People have criticised me for making fun of rather dim working-class people. But it was the government who assumed people were thick enough to follow such ridiculous advice."

The book was turned into an animated film in 1986 featuring Sir John Mills and Dame Peggy Ashcroft as the voices of the doomed couple and with anti-nuclear songs by Roger Waters, David Bowie and Genesis.

Briggs returned to a political theme in 1984 with a critique of the Falklands War entitled, The Tin-Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman, although the book was aimed squarely at young children. It underlined Briggs's reputation for tackling social issues head on.

Subversive

Ethel & Ernest, a 1998 graphic novel based on the lives of his parents, won him the Best Illustrated Book of the Year at the 1999 Book Awards. He later confessed it was one of the most difficult books he had written. He told the Guardian in 2004 that when drawing the scenes of his parents' deaths, he could work for no more than a quarter of an hour at a time.

The story was turned into an animated film and featured Jim Broadbent and Brenda Blethyn which, after appearing in cinemas, was aired by the BBC during Christmas 2016.

The death of his long-term partner, Liz, in 2014 - his first wife Jean had died in 1973 - saw him turning his attention to his own mortality in a work entitled Time For Lights Out, which he had tinkered with for years.

His grumpy Father Christmas featured on postage stamps in 2004

His work, often subversive, usually thought-provoking and always entertaining, marked Raymond Briggs as an author and illustrator of real genius

He did nothing to discourage his reputation as something of a grumpy man, epitomised in his Father Christmas character, once describing himself as "a miserable git" , although friends said that, away from public view, he was a generous and spirited figure.

His work was recognised with the award of a CBE in the 2017 Birthday Honours

Raymond Briggs was once asked by a journalist what was his preferred way to leave his life.

"Doing an interview," Briggs immediately replied with a twinkle in his eye, "and dying before the end of it."