Trump and the media - Is it war or love?

- Published

Are President Trump's attacks on the media undermining the news?

For the past week I have been in New York and Washington, talking to key players in the media here. By that, I don't just mean the hated mainstream media, whatever that phrase means. I've also spoken to conservative talk radio hosts who think of Donald Trump as an emissary from the promised land.

And I've come closer to understanding Trump's highly coherent media strategy. In short, his "war with" the media ought to be updated to "marriage to" - or "affair with".

It turns out, as I argued some weeks back, that the man alleged to be at war with the media is threatening to create a golden age for it. Whether liberal, conservative or neither; print, television, radio or web, this former reality TV star is boosting subscribers, traffic, ratings and revenues all over the shop.

Some people think Trump's pronouncements are not so much a media strategy as pure madness. Perhaps so. Yet - like Polonius - I detect method in it.

Three principles, simple and wholly unoriginal each, have coagulated to create it. In their variety and efficacy, they contain lessons not just on the psychology of this remarkable leader, but also the nature of modern media.

A dead cat on a table

First, Trump evinces a disarming fondness for dead cats. Not literally, you understand. I mean the dead cats that Lynton Crosby specialised in. You may recall that the Australian strategist, one of the most effective campaign managers and manipulators of media in modern history, had a habit of throwing 'dead cats' into the national conversation.

The technique is simple. If you and I were having a conversation, and then suddenly someone threw a dead cat onto a table, we'd stop talking about whatever riveting subject had heretofore detained us, and talk about the dead cat instead. Dead cats appearing out of nowhere are more interesting than most subjects of daily conversation.

Trump's tweet, external about his predecessor wire-tapping his phones is probably the most lively dead cat in our time. One simple claim - for which many US media say he lacks robust evidence, and that could not be substantiated by spokesman Sean Spicer - has dominated the news agenda for a week, and taken the sting out of stories about Trump's relationship with Russia.

Second, use digital media to speak directly to the base, without the filter of journalistic judgement and interpretation. Trump notoriously uses social media to cut journalists out of the picture. Why bother being interviewed by a pesky hack, when you have 26.3 million follower, externals on Twitter?

But because journalists are so fond of Twitter - it's a personalised news feed, after all - there can be a tendency to ignore Facebook, where Trump also has more than 20 million followers, external, who between them have social networks with hundreds of millions of people. And so too talk radio, which is a bigger phenomenon in the US than Britain. Trump often speaks to the likes of Rush Limbaugh.

Andrew Wilkow presents on a satellite radio channel with 30 million subscribers

Andrew Wilkow presents The Wilkow Majority, external on Sirius XM's The Patriot Channel, which boasts 31.3 million subscribers ("We're Right. They're Wrong"). He told me that conservative talk radio hosts have been uniquely effective in exploiting the opportunities of digital media. He said American journalism had for years been a "closed guild", but that had now been smashed open.

Third, favour conservative and even conspiratorial media outlets in press briefings. We know that Spicer, whose Spicer Doctrine asserts that it is the role of government to hold the media to account, has sometimes cut traditional media out of briefings.

A marriage of convenience?

We know that the most powerful voice in Trump's ear is that of Stephen Bannon, the anti-globalist who used to run Breitbart News.

And we know from his courting of Fox News that Trump will unashamedly focus his limited time for interviews on sympathetic outlets. He has also given plenty of time, for instance, to Alex Jones of Infowars.

Where do Donald Trump supporters get their news from?

I interviewed Mark Thompson, the former Director-General of the BBC who is now President and CEO of the New York Times. They have seen subscriber numbers soar.

When I asked if Trump's war with media was a marriage of convenience, Thompson told me that he certainly didn't think of his company as being in partnership with Trump - but there have been very sharp increases in willingness to pay for news.

The year-on-year increase in Times subscribers has added several million dollars in net revenue. They might have grown had Trump never run for office. But this much? No way.

It is, then, an abiding irony of our age that the sustenance of decent and often liberal journalism owes so much to a man who is instinctively suspicious of reporters and popularised the term "fake news".

Dean Baquet said Trump had helped the New York Times "clarify their mission"

Dean Baquet, the Executive Editor of the New York Times, said Trump had helped his team to "clarify their mission". After a decade of soul-searching, he added, the news industry has found that its new mission turns out to be similar to the old one: dig deep, find stuff out, and report it fairly.

When, a few weeks ago, this blog pointed out that far from being an enemy of the press, Trump is in fact its saviour, I wondered if comrades in the trade would be offended at the suggestion. To my surprise, many were sympathetic.

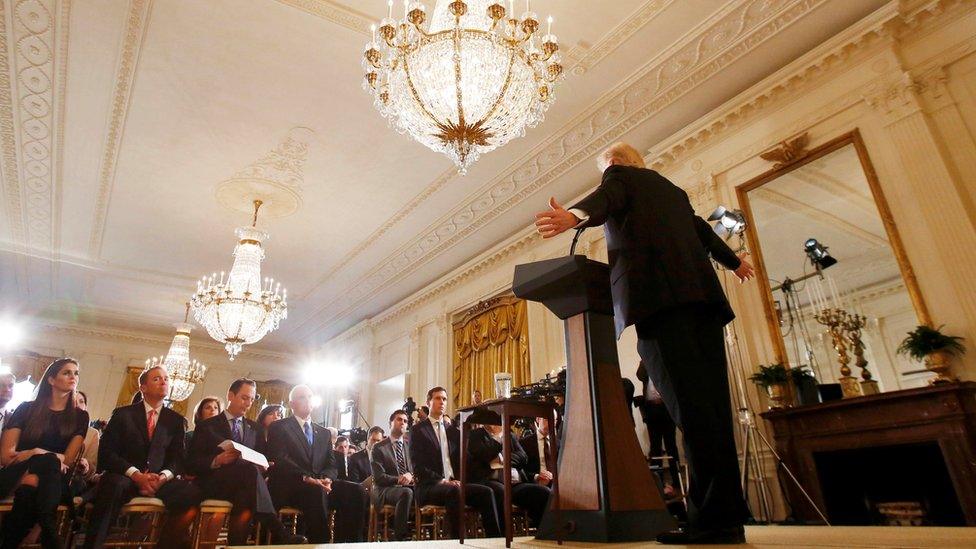

President Trump faces reporters during a news conference at the White House in Washington

Trump is a journalistic challenge in so many ways. How do you reconcile presidential falsehoods with the duty of impartiality? Should you really hang on his every tweet? What does political journalism look like when you get no access to the top?

Aside from all that, however, is another quandary. They might find him unappealing. He might seem hostile to all their most sacred principles. But Trump has put journalists - and journalism - in a debt to him that will never be fully serviced.