Fox and Sky: Is this time different?

- Published

Culture Secretary Karen Bradley has said she is "minded to" refer the bid by 21st Century Fox for the 61% of Sky it doesn't own to Ofcom, the regulator.

I am minded to be wary of ministers who adopt strong stances on issues while deferring decisions to other people - but more of that later.

For now, let's assume Mrs Bradley does indeed refer the bid.

Various sources tell me the timing depends on how much parliamentary time is consumed by Article 50, but Mrs Bradley has until Friday, and could announce as early as Wednesday.

The culture secretary says she has "concerns that there may be public interest considerations... that warrant further investigation"

media plurality

commitment to broadcasting standards

This week, Ofcom said it would, if Mrs Bradley referred the decision, also conduct a "fit and proper" test on James Murdoch.

In this blog, I will answer the following question: what's changed between the Murdoch family's last bid for full control of Sky, which had to be aborted, and this one?

In other words, is this time different?

James Murdoch is chairman of Sky and chief executive of 21st Century Fox

For James Murdoch - who always saw Sky as unfinished business, and who has spent most of his career growing entertainment rather than news businesses - there are two pillars to the argument that this is not merely a re-run - put simply: "The landscape has changed. We have changed."

Let's take these in turn.

It is undoubtedly true that news is undergoing a revolution.

You'd expect me to say that, given I owe my job to it, but it is true.

According to Ofcom, social media is now the primary source of news for more than a third of British Millennials (those born between 1982 and 2004).

Moreover, Ofcom says Facebook is the third biggest source of news, by number of references, for UK consumers, and as a result of this explosive growth in social media, a new generation is getting more news - albeit of variable veracity - from more places.

The average Brit now gets their news from 3.5 sources, compared with 2.9 back in 2010.

These are numbers used by 21st Century Fox to justify its claim that the news media is undergoing rapid transformation.

No sober observer could argue that the habits of news consumers are the same now as they were six years ago.

Political context

When the Murdochs last bid for full control of Sky, it was their news division, News Corporation, that proposed the deal.

In 2013, Rupert Murdoch split his company into entertainment and newspaper operations.

This time, the bid is coming from 21st Century Fox - essentially the entertainment side of the company, rather than the news division.

James Murdoch would argue that both 21st Century Fox and Sky are companies with independent boards, and that what this deal is really about is giving Fox better access to Sky's 22 million customers, who primarily consume entertainment rather than news.

Seeing this as a bid by one entertainment company for another is what James Murdoch means by "We have changed."

Of course, the biggest change between now and the last bid is the political context.

The Murdochs pulled out of their last attempt to take control of Sky because of public revulsion at the criminality within their British newspaper, and - crucially - the concerted effort of political opponents.

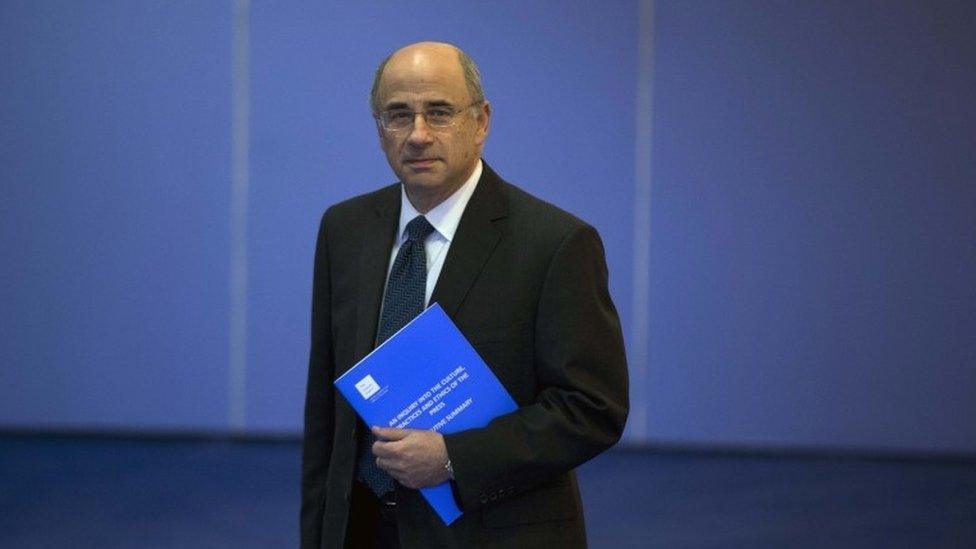

In 2011, the then News Corp chief executive and chairman Rupert Murdoch and his son James appeared before a parliamentary committee on phone hacking

Last time round, not only was there a more effective and co-ordinated Labour fight-back under Ed Miliband, who is strongly opposed to what he sees as vested interests in the media, but the Lib Dems were in government and counted enemies of Mr Murdoch among their most senior figures.

It was Vince Cable, of course, who told undercover reporters he had "declared war" against Mr Murdoch.

And, because former News of the World editor Andy Coulson worked for the prime minister, the bid became a prelude to a much bigger story about the relationship between the media, business, and politics.

Now, Mr Cameron is gone, Coulson has been to jail, the Lib Dems are shrivelled and no longer in government, Labour is less vocal on this subject - and, above all, the phone-hacking scandal has receded from headlines (and cultural memory).

Those, then, are the principal differences.

How would opponents of this bid counter these points?

First, they would argue that the division within the Murdoch stable is synthetic: this might be 21st Century Fox rather than News Corporation, but ultimately it's all the Murdoch family.

Secondly, they would argue that we need to have the second instalment of the Leveson Inquiry, which looks at police corruption and corporate governance (not least by James Murdoch), before a fully informed decision can be made.

Former Labour Prime Minister Gordon Brown said as much to me a fortnight ago.

Next, they would say that the shocking allegations about sexual harassment at Fox News, another Murdoch subsidiary, are another reason to query their corporate governance.

In New York last week, several senior figures in the media industry told me they were interested in whether the Fox News allegations would have an impact on Murdoch's ambitions in the UK.

And finally, these opponents would argue that for all the talk of new digital competitors and the rise of social media, the strength of Rupert Murdoch's newspapers here give him too much influence and control already, resulting in damage to our democracy.

Influence and control

To these counter-points 21st Century Fox would naturally say if you really want to know who has too much influence and control, take a look at the BBC, which is by a huge margin the most powerful voice in British media and culture.

That is a familiar refrain: James Murdoch in particular has been ferociously critical of the BBC, external.

These, then, are some of the ways in which circumstances have changed since the last bid - or, as some would have it, stayed the same.

In their remarkable history of financial crises, This Time is Different, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, external showed how, over centuries, investors and policymakers failed to learn the lessons of history, falsely thinking each big decision they made had no precedent.

Ofcom's decision on this bid, if indeed the culture secretary refers it, will hinge on whether this time is different.

Pipes with ideas

Has a clearly diversifying media landscape evolved enough to overcome historical concerns about excessive influence and the character of those who most want this deal to happen?

The latest bid, by the way, is wholly consistent with the trend across the media industry of consolidation - namely, the marriage of distribution and content, which I call pipes with ideas.

New competition for eyeballs from digital giants such as Netflix and Amazon is making those people who own the content - the storytelling of drama, news, documentaries, comedy and family entertainment - to get together with those who own the means of reaching customers.

In this instance, 21st Century Fox own the content, and they want full access to Sky's pipes.

As for the culture secretary's intervention, I would be wary of reading too much into the fruity language of her letter saying she was "minded to" refer the bid to Ofcom - or indeed in the energetic rebuttal it received from 21st Century Fox.

There is little political downside to making such a referral: it allows Mrs Bradley to issue bromides about media plurality, give the appearance of standing up to vested interests - and ultimately defer a decision to an independent regulator.

There has been no announcement yet whether the second stage of Lord Justice Leveson's inquiry will go ahead

Not that I have any reason to doubt her commitment to a raucous and successful media.

But the bigger decision she has to personally make (in conjunction with Theresa May) is whether to go ahead with the second, promised stage of the Leveson Inquiry.

This decision is just a warm-up.

Several government sources have told me their personal view that this second stage is either rendered unnecessary by the criminal trials since the first inquiry - or that a judge-led inquiry involving high-profile testimony would be a terrible distraction at a time when the government is trying to manage Brexit, and needs newspapers on-side.

When dealing with the Fox-Sky bid, Mrs Bradley knows her decision to refer (or not) won't be subject to the same scrutiny or political heat as her decision, made in conjunction with the prime minister, on Leveson Two.

- Published15 December 2016

- Published3 March 2017