Do the technology giants finally face a backlash?

- Published

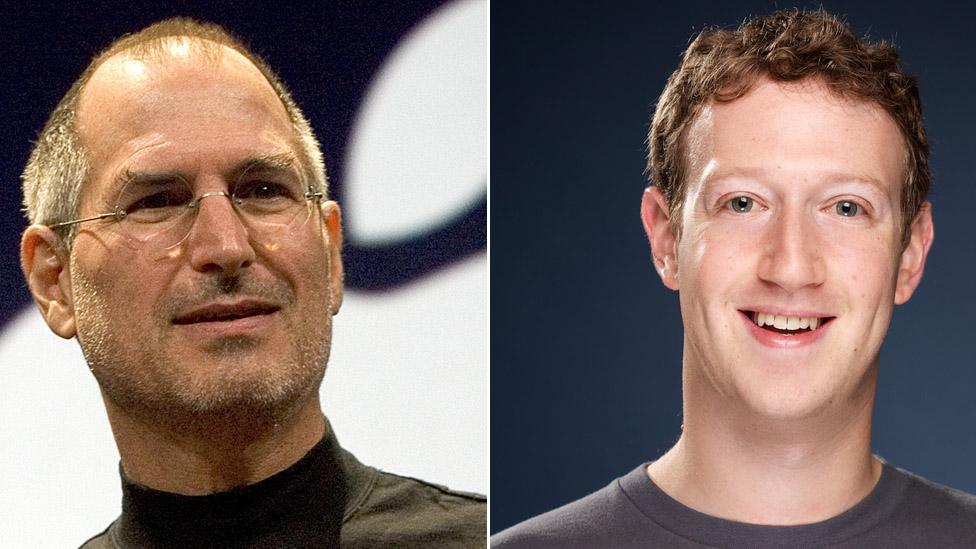

Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg: a shared philosophy

It is perhaps the most beguiling irony of our age that a new class of super-rich that has emerged on America's West Coast has its moral, intellectual and even spiritual origins in the anti-materialistic radicalism of 1960s counter-culture.

Silicon Valley is what happened when the flower power generation sobered up.

Steve Jobs was a Buddhist, though to what extent has been the subject of much debate.

And the zealous mission on which Facebook is embarked - to create a more open and connected world, smashing barriers instinctively - owes a substantial debt to the baby boomers and their own particular doctrine, (John) Lennonism. When Mark Zuckerberg speaks, I always hear the lyrics to Imagine.

Perhaps it is this moral component to what Silicon Valley's biggest companies do that has, for the most part, protected them from what I had long considered inevitable: a monumental backlash.

Tech-lash

I call this the tech-lash, external, and thought it would have two main components.

First, anti-capitalism: the hostility toward plutocracy shown by groups such as Occupy Wall Street would, eventually, take aim at the astronomical wealth of tech billionaires - especially once it dawned on these protesters, and society at large, that compared to the industrialists of old, these companies don't actually employ many people.

As a result, of the vast capital they have amassed, a disconcertingly small amount actually makes it to the labour force.

That smells like trickle-down economics - without the trickle down.

The second component of the tech-lash would arise from concerns about privacy, fuelled not least by the revelations from Edward Snowden.

It is hard to get your head around just how much data companies such as Google and Facebook hold, and how much information they have about us - most of it voluntarily given over.

If the civil liberties brigade ever needed a cause around which to rally, this could well be it.

Together with disgust at how little taxes these companies pay, you have the elements of an almighty revolt.

And yet, it hasn't really come: partly, I imagine, because of that sense of moral purpose; and partly because of the fact that these brilliant and uniquely innovative companies have improved our lives without asking us to pay a penny.

Your appetite for being horrible toward Google is neutered when you use Gmail to rally comrades to a cause, and Google Maps to get to a protest.

Changing mood

This, then, was the tech-lash that wasn't. Until now.

Two stories this week suggest that the mood is changing.

On Tuesday, the Home Affairs Select Committee gave a ferocious grilling to senior executives from Facebook, Google and Twitter.

Google, Facebook and Twitter faced the Home Affairs Select Committee

The Daily Mail is usually a good indicator of which way the wind is blowing; its front page headline on Wednesday was "Shaming of the web giants".

The next story that showed public feeling might be turning was on the front of another British newspaper - the Financial Times.

And yet the story wasn't about Britain. The splash headline was: "Berlin plans €50m [£44m] fines for hate speech and fake news".

This is a remarkable story: the German government is drafting legislation that will aggressively target internet companies, including social media giants, if they don't do enough to stop the spread of socially corrosive material online, particularly by giving users tools to flag such material.

Germany is uniquely susceptible to the spread of fake news.

The Daily Mail's hard-hitting headline

Angela Merkel's hugely controversial refugees policy, the rise of the nationalist Alternative for Germany party, the constant threat from neo-Nazis, upcoming national elections, and the staid media landscape - staid compared with Britain's raucous tabloids, for instance - all make conditions ripe for exploitation.

But Germany is now leading the fight-back. Germans have a very different approach to the state to that which is fashionable on America's West Coast.

The new tech giants are often libertarians who believe that innovation and technology can solve social problems much more effectively than government.

They are diametrically opposed to what you might, crudely, call the Teutonic faith in regulation: many Germans - and indeed all those I spoke to while reporting there - believe that a smart, enabling state can, through effective legislation, mitigate social ills.

If the much heralded tech-lash is finally upon us, it is the Germans who hold the whip hand.

It isn't hatred of plutocracy, or love of privacy, that finally turned the temper of a people against tech giants: it is the threat of election, and legislative power falling into the hands of nasty forces, that has prompted action.

Moreover, it took the German faith in the efficacy of regulation to confront those giants with the threat of punitive action.

If the German proposal becomes legislation, it will offer a template that could be rolled out elsewhere.

Whether this is the beginning of a tech-lash - a concerted effort by societies and government to, ahem, take back control from tech companies - or just an incremental development in a constantly maturing new world of law and power, is unclear.

I would hope, whatever the regulatory fallout of the fake news phenomenon, the likes of Facebook and Google continue to earn immense respect for being better at providing exceptional services to customers than most companies in history.

Will the UK follow?

Does that include the British? Yes, basically: our political class reveres Silicon Valley and hopes to replicate its success over here.

But my conversations in Westminster lead me to believe that, in Theresa May, we have a leader who is not far off the pragmatic, populist patriotism of Mrs Merkel; that, like the German chancellor, our prime minister is a provincial Tory who believes in the good that government can do.

Theresa May admires the pragmatism of her German counterpart, Angela Merkel

Given her one-nation rhetoric, Mrs May will be conscious that fake news - which Facebook is taking very seriously - does potentially pose a threat to the social solidarity.

The prime minister and her most senior lieutenants are very close observers of German affairs, and there are people close to the top of British government who are wondering what they can learn, and imitate, from this week's German proposal.

In recent years, the moral fervour of those sons and daughters of the 1960s who have come to dominate Silicon Valley, and all our lives, has forged an alliance with wealth and power of a kind most of us can't imagine.

What happens when it clashes with the alternative worldview of people in faraway lands who have elections to win, and hatred to silence, will determine much of this, the first truly digital chapter in history.