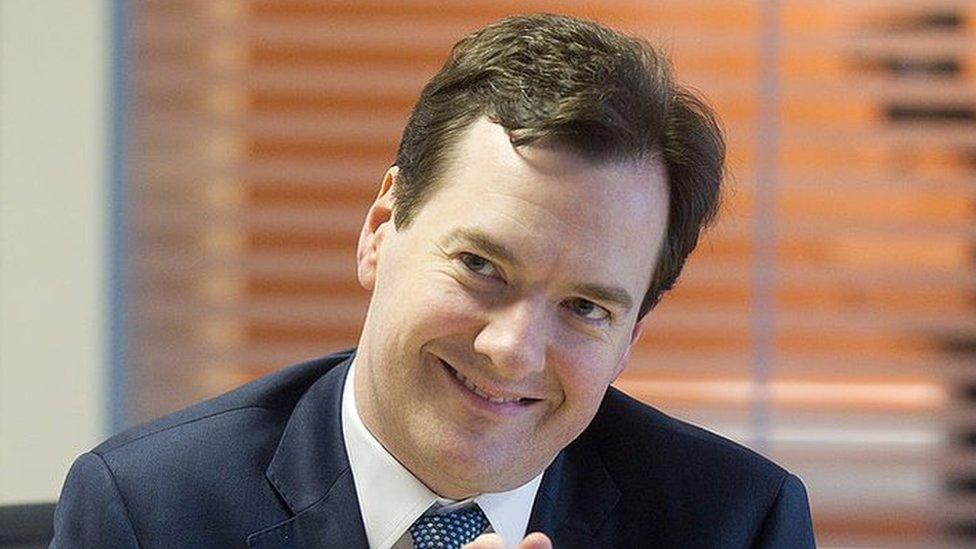

George Osborne: From history buff to austerity editor

- Published

George Osborne is a history buff at heart.

A student of modern history in his undergraduate days at Oxford, his is that cast of mind with a tendency to see himself as the inheritor of distant traditions.

When I had a cup of tea with him in No 11 a couple of years ago, he spent the first seven or eight minutes talking about the provenance of the grand portraits in his room, and the figures there depicted. I got the message pretty clearly. Here was a historic figure, he seemed to imply, who felt he had no judge so fair or firm as posterity.

"He's fascinated by history," the Tory MP and historian Keith Simpson told the Financial Times, external a few years ago. "He looks at different historical institutions and mechanisms which may have lapsed and sees whether they can be given new life."

Like the mechanism by which being an MP is very much a part-time job, perhaps.

Osborne will need to mobilise all his knowledge of history when defending the decision to mix two full-time jobs - that of an MP and a newspaper editor - with each other, let alone with his four days a month at BlackRock, the asset manager, for which he gets an annual figure of £650,000 - what most people earn in around a quarter of a century.

Many journalists, including Winston Churchill, have gone on to be politicians

The fact is, he has no journalistic credentials whatsoever.

Most people who edit newspapers will have spent years crafting headlines, sub-editing copy, designing pages, planning stories, and above all reporting.

Osborne has never done any of that, and will need to grasp some basic skills very quickly if he is to keep Standard staff on-side.

Of course, there is a long tradition of journalists becoming politicians, from Churchill and Horatio Bottomley to Nigel Lawson, Ed Balls, Yvette Cooper, Michael Gove, Ruth Davidson, Benito Mussolini (who edited two socialist papers) and the fictional Jim Hacker.

Fewer have tended to go the other way. Bill Deedes was an editor of a newspaper (the Daily Telegraph) and a cabinet member, though not at the same time.

Boris Johnson, who in ancient history was thought of as Osborne's main rival for the Tory crown, was editor of the Spectator while MP for Henley. And, long before he entered politics, Michael Foot was editor of the Standard at 28.

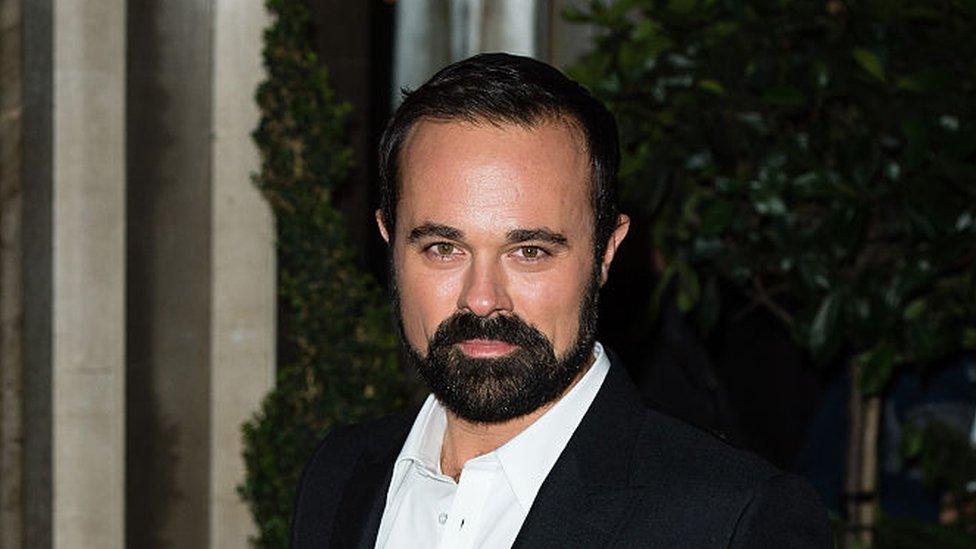

Evgeny Lebedev, the 36-year-old who is now Osborne's boss, is fond of Evelyn Waugh and 20th Century literature generally (full disclosure: I was for several years Lebedev's adviser, and then his editor at the Independent).

I imagine Lebedev will like the idea of reviving quaint, romantic 20th Century ideas about the relationship between politics and newspapers.

The Standard's owner, Evgeny Lebedev

But Osborne's constituents have daily concerns that are more rooted in 21st Century Britain. He has a huge majority, but together with his four days a month at BlackRock - which is around a fifth of a full-time job in itself - he won't have much time for parliamentary representation.

Frankly, I can't see this arrangement lasting. Perhaps forthcoming boundary changes to the constituency will concentrate his mind - and that of his electorate.

Tatton has a population of around 85,000, which intriguingly is almost exactly a tenth of the Standard's readership. The latter are his new constituency. What kind of editor will he be for them?

Osborne flirted with journalism before entering politics. Years ago he was interviewed for a job, external on the Economist, the publication whose world view he most closely adheres to, by Gideon Rachman, now the Financial Times' brilliant foreign affairs commentator. He didn't get the job, despite having grown up on the same street as Rachman, and having the same first name (Gideon) and alma mater (St Paul's).

There is a strong resemblance between the politics of the Standard, which backed the Remain camp and Zac Goldsmith's mayoral campaign, and Osborne's: globalist in outlook, metropolitan rather than provincial, socially liberal, unashamedly in favour of capitalism, and reliably Tory.

The Evening Standard has a circulation of 850,000

In the past, Osborne has also spoken at length about his faintly bohemian upbringing, and his interest in the arts, particularly theatre, is genuine.

Naturally he will sharpen the paper's political edge, and his appointment serves up the truly delicious prospect of several assaults, under varying degrees of disguise, on the prime minister who so unceremoniously dispatched him to the back benches.

Ultimately he will be judged not just on the paper he produces, but on whether together with the commercial team at ESI Media he can reinvent the company.

Heavily reliant, like Metro, on print display advertising which is disappearing at the rate of around 20% a year across the industry, ESI Media - which houses the Standard, Independent, and TV station London Live - needs to be re-engineered, perhaps with events, data and ticketing to the fore.

Among his key lieutenants beyond the editorial floor will be Manish Malhotra, the former finance director who now runs the company, and Jon O'Donnell, the managing director for commercial whose ad team is outperforming the rest of the market.

Osborne was one of 30 applicants, 10 of whom were interviewed, and four of whom were shortlisted.

In four meetings in central London with Lebedev, he sought and received reassurance about the proprietor's willingness to invest in the paper and its website.

George Osborne addresses staff at the Evening Standard

He can take heart from the fact that the Independent, which is now digital-only (I was the last editor of the print edition) is now humming commercially, well ahead of budget and set to make a multi-million pound profit this year.

Unimaginable even three years ago, the Independent is currently the financial powerhouse within ESI Media, of which TV channel London Live is the other component.

The Independent is co-owned by Justin Byam Shaw, who is also the chairman of the Standard and attended two of the four meetings between Lebedev and Osborne.

Relative to the rest of Fleet Street, Osborne won't have much in the way of an editorial budget, and the need to raise revenues means sponsored content and native advertising of a sort that journalists instinctively resist may creep further into his pages.

Then again, doing more with less - or austerity - was the ethos that defined his contribution to political history. Not in this for the money, because he will be paid substantially less than his predecessor, the Austerity Chancellor has just been reborn as the Austerity Editor.

What his constituents make of that we're about to find out.

- Published17 March 2017

- Published25 November 2016