Why I've changed my mind about Henry Moore

- Published

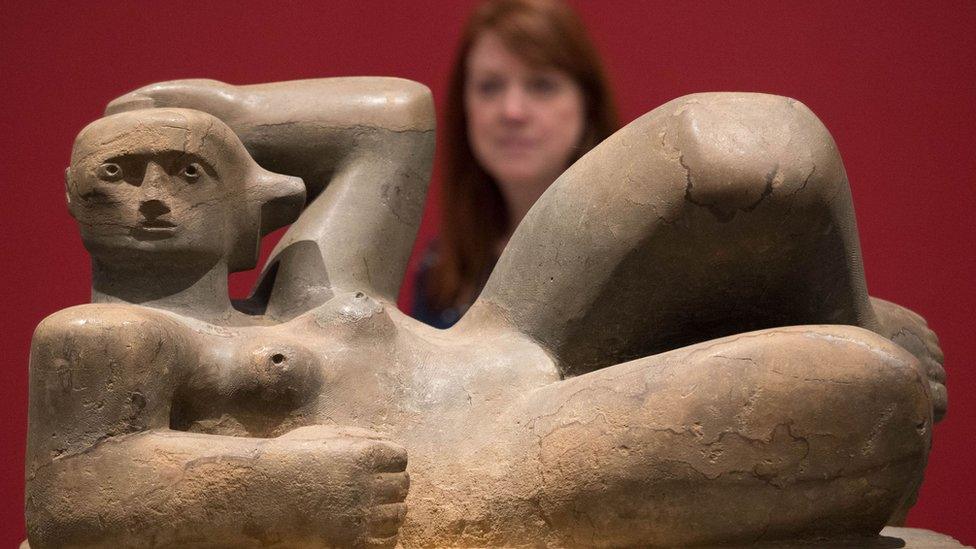

Moore's Reclining Figure (1929) is part of a new exhibition at the Henry Moore Foundation

You really can have too much of a good thing.

Champagne tastes like sheet metal after the third glass. Sunbathing gives you cancer. And the ubiquity of Henry Moore sculptures in English market towns in the 1970s put me off his work for a quarter of a century.

Back then, in Harold Wilson's Britain, Moore's monumental stone figures and giant abstract casts had the same worthy municipal feel as the local town hall.

Any conurbation large enough to support a Boots, a cinema and a public convenience seemed compelled to plonk an enormous Moore sculpture on a prize piece of public real estate.

His misshapen family groups and huge pierced boulders of bronze were like those fashionable avocado bathrooms - not nearly as groovy as the older generation thought. More Abigail's Party than the Sex Pistols.

The Henry Moore Foundation has just had a £7m revamp

I wasn't alone in wanting no more Moore.

In 1967, he offered the Tate Gallery "20 or 30 major pieces". Fellow artists were less keen, saying it was wrong to devote so much space to a single living artist (Moore had insisted his gift be on permanent display, which would have taken up a sizable chunk of the Tate's sculpture galleries).

The Tate declined - and the artist gave the work to a grateful Art Gallery of Ontario instead.

That was then.

Forty years later, I have aged, and so have Moore's sculptures. They have fared much better than me - they look terrific now.

Maybe it's their sense of calm permanence in our superficial, super-fast world, or my romanticising of Moore's post-war vision of modernity.

Either way, it was a pleasure to spend yesterday at his old home in Perry Green, Hertfordshire, which is now The Henry Moore Foundation.

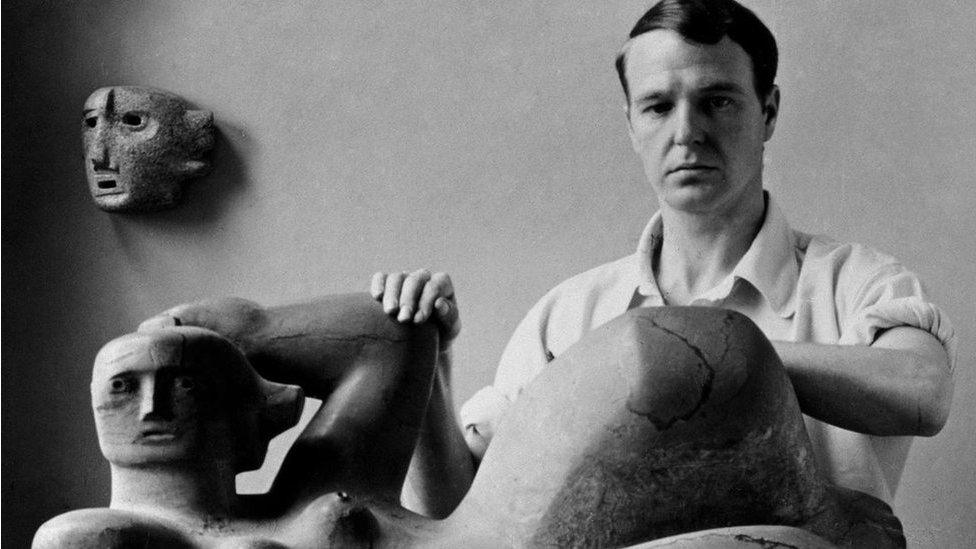

He was a sincere and dedicated artist who knew he wanted to be a sculptor aged 11, had his first commissions in his teens, and went on to excel at the Leeds School of Art.

There he met and befriended another aspiring young sculptor called Barbara Hepworth, who, like Moore, was inspired by the Yorkshire landscape of their birth.

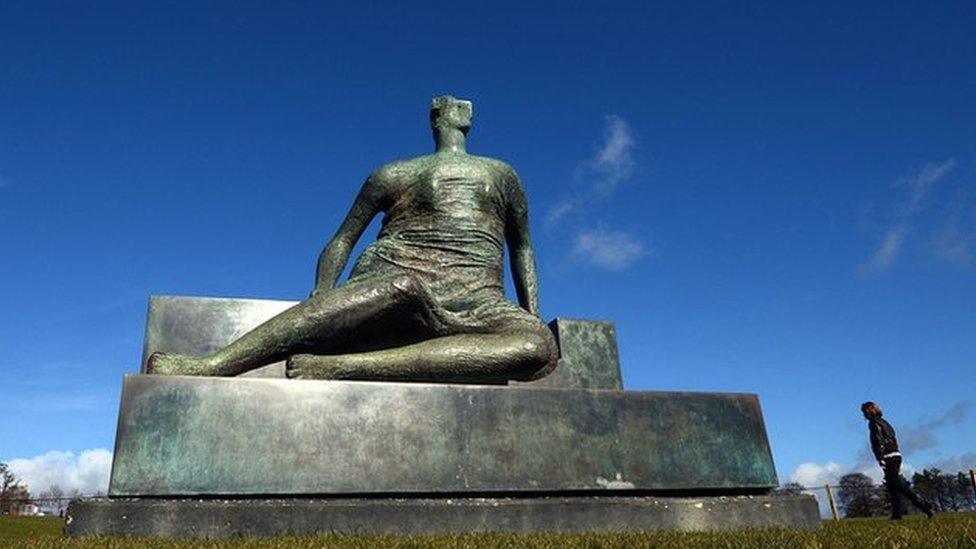

Sheep wander past Henry Moore's sculpture Large Reclining Figure at Perry Green

He read widely, immersed himself in art and drew on influences far and wide, from primitive African artefacts to Parisian Cubism.

His intellectual and technical wherewithal enabled him to successfully incorporate all these ingredients into harmonious, pleasing forms that feel both ancient and modern.

It's what gives his work such broad appeal and why it can be seen in hundreds of cities around the world - there is something in it for everyone.

His drawings of sheep and apple trees have an intensity and energy that feels kinetic. You'll see plenty of the real thing if you sit at his old oak desk in the little shed with a picture window that looks out onto the fields of sheep that frequently wander over to look at you.

There are some good drawings from his student days, which you can see in an exhibition opening this Saturday at the Foundation called Becoming Henry Moore.

There are plenty of sculptures, too, in the exhibition and dotted about the 70 acres of landscape, which the canny Moore used as a showroom for potential clients.

They look good. Much better than they did in those tired old market towns.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published12 April 2017

- Published28 March 2017