Is 2017 the year of virtual reality film-making?

- Published

Draw Me Close involves an actress in a motion capture suit who interacts with you live

The Tribeca Film Festival, opening this week in New York, is promoting virtual reality (VR) as never before. And next month the Cannes Film Festival has announced it's to show its first big VR attraction. So is 2017 the year virtual reality film-makers finally hit the big time?

Bogart Street in Bushwick has the mix of occupants you might expect in a formerly blue-collar but increasingly artsy corner of Brooklyn.

Number 56 is the four-storey home of small art galleries, jewellery designers and miscellaneous media start-ups.

Part of the basement is occupied by Scatter, which calls itself an immersive media studio.

Only a few years ago terms such as "immersive", "experiential", "volumetric" and "virtual reality" were on the outer fringe of film-making.

Yet recent analysis claimed that by 2021 the VR industry could generate revenues of $75bn (£60bn) annually.

Some older hands in the film industry are wary of such optimism - but they're also watching the rapidly developing VR world with a keen eye.

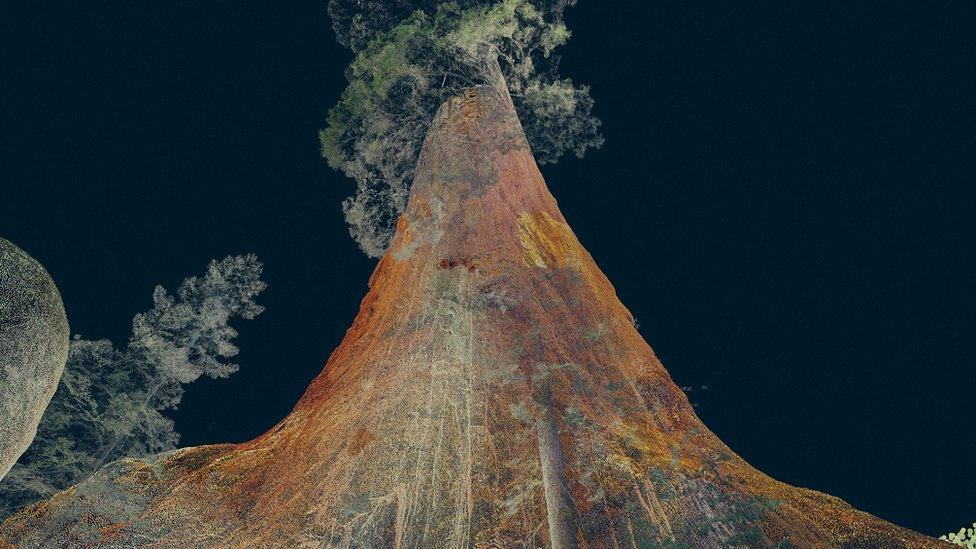

Treehugger allows viewers to put their heads through knotholes into the tree with the aim of changing perceptions

James George, co-founder of Scatter and technical director of Blackout, which the studio is showing at this year's Tribeca, calls it an experience rather than a film.

"You put on a headset and you're in a totally convincing virtual depiction of a New York subway car. In the car, which you can move about in, are various characters and as you turn to look you hear what each person's thinking.

"So someone is depressed about getting older and another person is thinking about doing their nails or whatever. The headset detects who you focus on through your head and eye movements.

"The term virtual reality now covers a whole array of audience experiences and the technology is changing constantly. What we do in Scatter draws deeply on the history of film-making and in no way rejects it. There's more than a century of experience there in how to tell a story effectively.

"But we build on that sensibility and those skills and we expand into room-scale holographic experiences.

Treehugger is described as an installation

"Though the movie comparison is good, there's also a link to immersive live theatre which a company like Punchdrunk offers in something like Sleep No More where the audience is mobile and surrounded by the action.

"This whole desire to move into immersive is a generational shift. A new generation is demanding participation in their media - which you can call interactivity. So everyone showing at Tribeca will have their own slightly different model of VR - and we all have our own means of trying to make it work financially."

Broken Night is a very different VR experience also viewable at this year's Tribeca. It's the work of Eko, a tech and media company based in Manhattan. Eko's Alon Benari says the project has an overlap with traditional film-making but is also different.

"We were lucky that Emily Mortimer and Alessandro Nivola [real-life husband and wife] were keen to come on board to play key roles on screen," he says.

"So they play a married couple - and at a certain point a gun is fired. It's hard to say much more because exactly what happens when you have the head-set on depends on which storyline you follow. The viewer explores the woman's memories and to a degree constructs them."

The Protectors, from director Kathryn Bigelow, will be shown to 250 people at a time all with headsets

But co-director Tal Zubalsky says it's not a case of the viewer determining the storyline.

"The interactivity is there to increase the viewer's emotional involvement, not to give them control - this isn't like winning points in a video game," he explains.

"But we're all learning and that's why Emily and Alessandro wanted to co-produce: suddenly traditional film-makers want to understand this new world. They were with us for two days on location, shooting on a Nokia Ozo, to make a six-minute film."

Like Blackout, Broken Night depends on an individual viewer experiencing the narrative in a headset. Some VR experiences at Tribeca will offer multiple headsets but the problem of making a profit with limited audiences is obvious.

Benari admits that for now distribution of a film like Broken Night is a challenge. "But you need to look at the level of excitement in the creative world, in investors and increasingly in consumers," he says.

"Technology will figure it out even if for now it's like the early days of silent movies or radio. No one can say if a version of today's headsets will be the medium of mass distribution at all: maybe it will all be embedded in eyeglasses or contact lenses or maybe it will be a hologram experience we don't yet understand.

"Then we can have audiences not of one person or three people but hundreds.

Audiences need to be convinced that VR films are a lot more than Hollywood-style 3D, says the festival's VR programmer

"Once you reach mass distribution with content which audiences really want - that's when there's huge monetisation. We are not there yet but if you look at the investment in VR, it's going to happen."

Loren Hammonds is the overall programmer for VR at the Tribeca Festival. "We had VR content last year but even in 12 months it's remarkable how things have grown. And we all wanted Tribeca to stay in the forefront.

"The kind of immersive film-making we're most interested in puts story first. It might be a thriller like Broken Night or something far remote from that.

"But increasingly we're seeing the tech used in clever ways to support a narrative, whether fiction or documentary. We've already gone beyond the demo phase of just explaining what the bells and whistles can do.

"Now we're into an adoption phase. Some people know all about VR but now the general public needs to be introduced to it so people see it's a lot more than Hollywood-style 3D.

Optimistic future

"Our Virtual Arcade will have around 30 experiences, with two thirds of them world premieres. I'm thinking of it as a street filled with curiosities - some of which you will love and some you probably won't. But it will be a great place to see the latest VR and for practitioners to talk.

"You might be on a swivel-chair with a 360-degree world around you and other experiences are positional, meaning you can actually walk around within a physical room. I'm looking forward to an installation called Treehugger by Marshmallow Laser Feast where you can put your head through knotholes into the tree and it will change your perceptions.

"Or there's an experience called Draw Me Close by Jordan Tannahill which actually involves an actress in a motion capture suit who interacts with you live. It's co-produced with the National Theatre in London and you might say it's something totally different again. But it's all VR."

Hammonds is optimistic about VR financially. "It's changing every month. But we've got the premiere of Kathryn Bigelow and Imraan Ismael's The Protectors. That's a mass trigger event, with 250 people in a room and they all have headsets and have the same experience at the same time. So VR needn't just be for one person at a time.

"I can't guess what VR we'll be showing at Tribeca a couple of years from now - or how people will see it. But the richer the content is, and the more compelling, the more it warrants being paid for. That's when we have an industry and a legitimate visual medium."

The Immersive Virtual Arcade runs as part of the Tribeca Film Festival in New York 19 - 30 April.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.