How many people does it take to write a hit song?

- Published

Canadian star Drake listed seven co-writers on his hit single One Dance

For decades, songwriting duos dominated popular music: Lennon and McCartney; Jagger and Richards; Benny and Bjorn.

Not any more.

A new study by Music Week magazine, external shows it now takes an average of 4.53 writers to create a hit single.

The publication analysed the 100 biggest singles of 2016, and found that only four were credited to a single artist - Mike Posner's I Took A Pill In Ibiza, external, Calvin Harris's My Way, external; and two, external separate hits, external by rock band Twenty One Pilots.

Ten years ago, the average number of writers on a hit single was 3.52, and 14 of the year's top 100 songs were credited to one person, including Amy Winehouse's Rehab, external and Arctic Monkeys' When The Sun Goes Down, external.

Amy Winehouse performs Rehab on Later... with Jools Holland in 2006

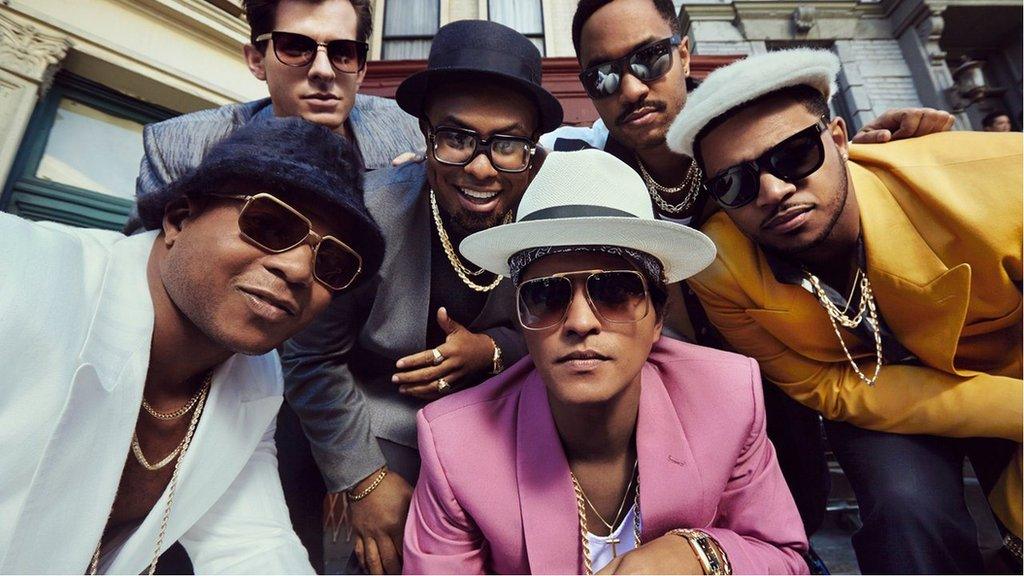

The best-selling song of 2016, Drake's One Dance, external, needed eight writers - but even that pales into insignificance compared to Mark Ronson's Uptown Funk, which took 13 people to create, leading Paul Gambaccini to brand it "the most written song in history".

(To be fair, Uptown Funk originally listed a mere four writers, but others were added when it was noticed the song bore a resemblance to The Gap Band's 1979 hit Ooops Upside Your Head.)

Even solo singer-songwriters like Adele, Taylor Swift and Ed Sheeran, whose identities are deeply ingrained into their music, lean on co-writers; while rock band U2 have been working with hitmakers like Ryan Tedder, Paul Epworth and will.i.am on their new record, Songs of Experience.

So why is this happening? Are songwriters increasingly lazy or lacking in talent? Or are they second-guessing themselves in the search for a hit?

Just a few of the writers credited on Uptown Funk

According to Mike Smith, managing director of music publishers Warner/Chappell UK, it is simply that the business of making music has changed.

"Think back 20 years and an artist would take at least two or three albums to really hone their craft as a songwriter," he told Music Week.

"There is a need to fast-forward that process [which means record labels will] bring in professional songwriters, put them in with artists and try to bring them through a lot faster."

Writing camps

Swedish star Tove Lo, who wrote tracks for Girls Aloud and Icona Pop before launching her own career, says "writing camps" helped her find her voice as a songwriter.

"Before I signed to Warner Chappell as a songwriter, I wrote by myself and I produced myself," she told the BBC. "But I learned a lot from working with producers who had more of an idea.

"I was always so focused on melody and lyrics. And most of the songs I've written by myself - like Habits, external - are three chords the whole way through.

"But the build-ups and dynamics, I didn't really know how to get there production wise. The Struts, who produced [my first] EP, they're really good at the dynamics. When I started working with them, I learned how to get that feeling."

MNEK explains how he made his new single At Night (I Think About You)

Writing camps are where the music industry puts the infinite monkey theorem to the test, detaining dozens of producers, musicians and "top-liners" (melody writers) and forcing them to create an endless array of songs, usually for a specific artist.

"They love to give you a bit of a brief, like, 'This song should be uptempo, sassy, girl-meets-guy,'" says British singer Dyo, a veteran of camps for X Factor contestants, who is up for an Ivor Novello award this week for her hit single Sexual, external.

"But I just ignore briefs. Briefs are corny. Everyone wants to write good songs. I'm all for writing good songs."

Churning out hits

Pop singer RAYE, whose writing credits include Charli XCX and Jax Jones, adds: "Some writing camps are very weird and factory-like.

"I remember the Rihanna writing camp - they booked out a massive studio, and they'd have a writer in each room, trying to churn out as many songs as they could.

"They're quite weird. There's a lot of pressure - but you do get songs."

Synth-pop band Chvrches avoided the temptation to work with co-writers

All this unfettered creativity sounds idyllic, but there is a downside. If you have 13 writers on a song, each of them gets a slice of the royalties when it's purchased or played. And the money doesn't get shared equally, which means lesser-known writers who contribute a line or a lick to a hit song may only get 1% of the profits.

And then there's the issue of homogenisation. If the world's biggest artists all employ the same writers, could your dad actually be right when he claims "all music sounds the same these days"?

Losing identity?

For Scottish pop band, Chvrches, that's a real risk.

"People don't make albums any more," synth player Iain Cook told BBC News in 2015. "They make 11, 12 songs, and they put them out as an album but they feel like a greatest hits, or a playlist.

"And maybe out of those 10 or 11 songs, those co-writes that you do, there's a global number one. But it's not yours."

Singer Lauren Mayberry added: "When I listen to our record, I listen to it and think, 'that has a strong identity.'

"That's something you can't say when it's a record full of co-writes. I think that would just dilute the identity of it."

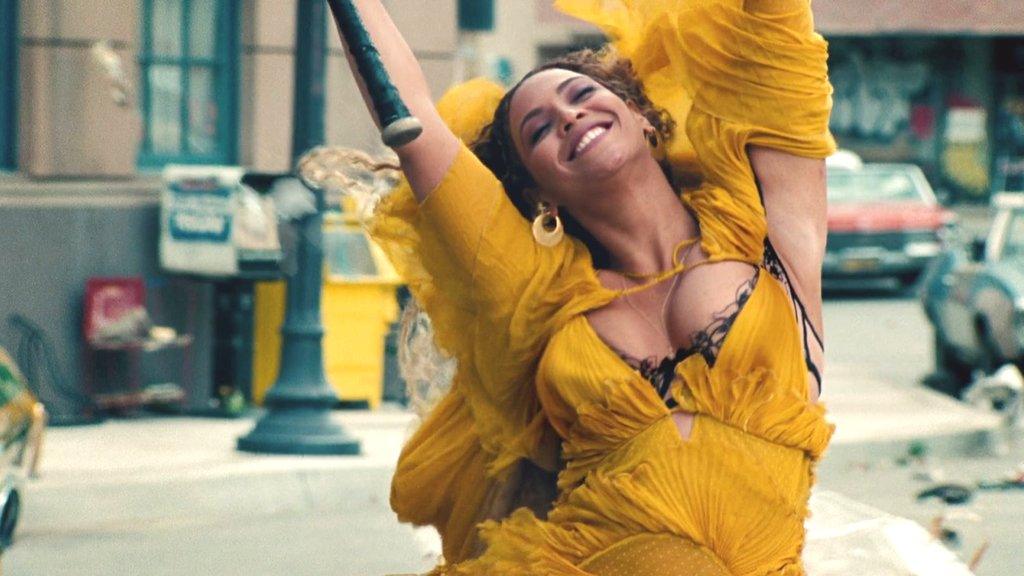

Beyonce manages to create a sense of ownership, even when she collaborates with dozens of writers

Crucially, an artist needs to stamp their identity on those writing sessions - a skill Beyonce perfected on her last two albums, which are intimate and autobiographical despite the huge volume of contributors.

British songwriter MNEK, who is one of 13 people credited on Beyonce's hit single Hold Up, external, says the song is essentially a Frankenstein's Monster, stitched together from dozens of demos.

"She played me the chorus," he told the BBC last year. "Then I came back here [to my studio] and recorded all the ideas I had for the song.

"Beyonce snipped out the pieces she really liked and the end result was this really great, complete song."

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published1 May 2015

- Published11 July 2016